Human rights according to the United Nations, are rights we have simply because we exist as human beings – they are not granted by any state. These universal rights are inherent to us all, regardless of nationality, sex, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, language, or any other status. They range from the most fundamental – the right to life – to those that make life worth living, such as the rights to food, education, work, health, and liberty. In Europe not all have these rights, if one only relies on the European Convention on Human Rights. The European Convention includes an article that limits this for persons with psychosocial disabilities. It came from someone and somewhere, and for a reason. This is the story of what was behind.

The European Convention on Human Rights drafted in 1949 and 1950 in its section on the right to liberty and security of person have noted the exception of “persons of unsound mind, alcoholics or drug addicts or vagrants.” The exception was formulated by representative of the United Kingdom, Denmark and Sweden, led by the British. It was based on a concern that the then drafted human rights texts sought to implement Universal human rights including for persons with psychosocial disabilities, which conflicted with legislation and social policy in place in these countries.

Eugenics movement

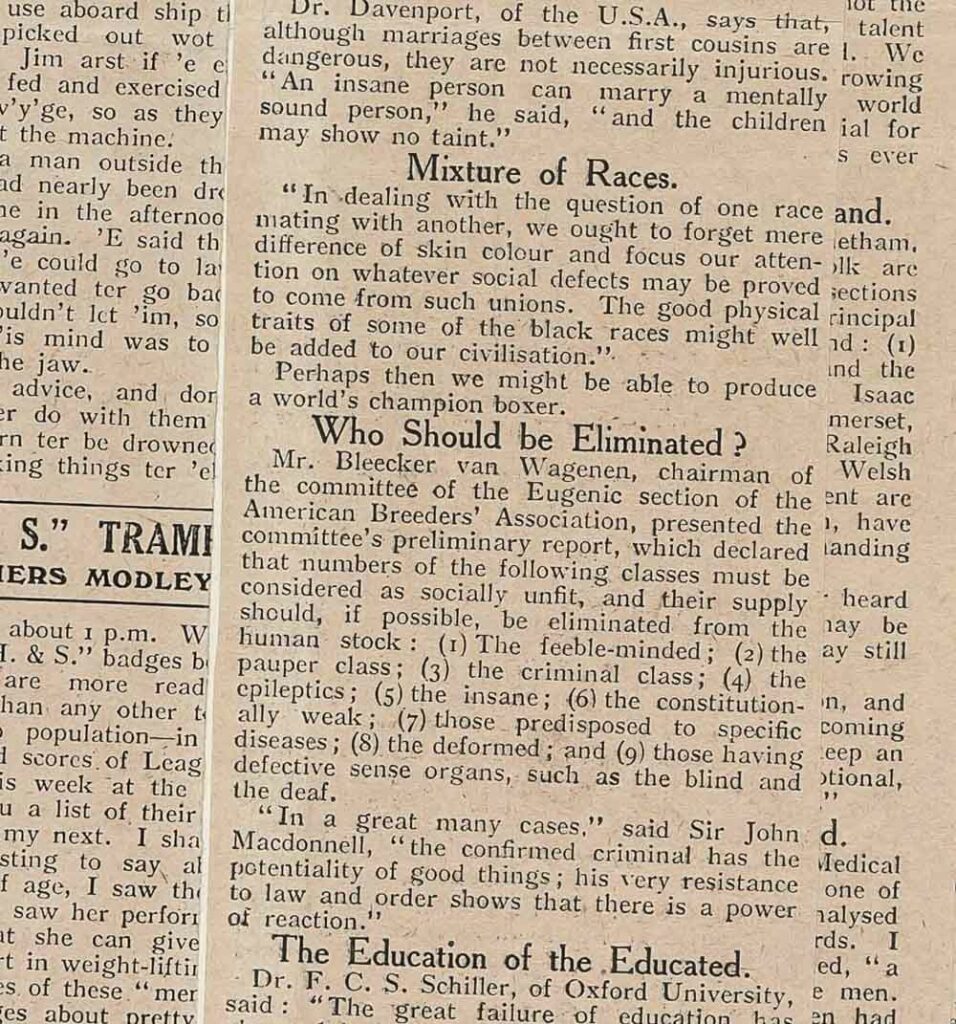

In the late 19th century, the eugenics movement of our time emerged in the United Kingdom. Eugenics was popularized and from the first part of the 1900s, persons from across the political spectrum adopted eugenic ideas. As a consequence, many countries including the United States, Canada, Australia, and most European countries, including Denmark, Germany, and Sweden got involved with eugenic policies, intended to “improve the quality of their populations’ genetic stock”.

The eugenics programs included both so-called positive measures, that encouraged persons deemed particularly “fit” to reproduce, and negative measures, such as marriage prohibitions and forced sterilization of persons deemed unfit for reproduction, or simply the isolation of such persons from the society. Those deemed “unfit to reproduce” often included people with mental or physical disabilities, people who did not do well on IQ tests, criminals, alcoholics and “deviants”, and members of disapproved minority groups.

In the United Kingdom, the Eugenics Education Society in the early 1900s had a growing attention on “curing” a number of social and physical conditions or traits among the poor. They included alcoholism, habitual criminality, reliance on welfare, prostitution, diseases such as syphilis and tuberculosis; neurological disorders such as epilepsy; mental conditions such as insanity, including hysteria and melancholia; and “feeble-mindedness” – a catch-all term for anyone who was believed to lack mental capacity and moral judgement.

The Society was never very large, but it was very vocal and its propaganda both reflected and promoted views that were held throughout the upper levels of society, including in the government.

The Society organised the First International Eugenics Congress in 1912, at the University of London, to promote eugenics. The British vice presidents of the congress included the Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna.

© Wellcome Collection. Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

The Mental Deficiency Act

Following the congress, Reginald McKenna, later in 1912 on behalf of the Government, launched a eugenics-based bill that included forced sterilisation. It was designed to prevent “the feeble-minded” from becoming parents. The bill met strong resistance and became the subject of considerable discussion. The bill in an amended form got enacted the following year as the Mental Deficiency Act of 1913. The Act in part due to the opposition rejected sterilisation, but it made it legally possible to segregate “mental defectives” in asylums.

With this Act a person deemed to be an idiot or imbecile could be placed in an institution or under guardianship if the parent or guardian so petitioned, as could a person of any of the four categories a) Idiots, b) Imbeciles, c) Feeble-minded persons, and d) Moral Imbeciles, under 21 years. It also included persons of any category who had been abandoned, neglected, guilty of a crime, in a state institution, habitually drunk, or unable to be schooled.

Tens of thousands of persons as a result got locked up in institutions. According to one study 65,000 persons were placed in “colonies” or in other institutional settings, at the height of operation of the UK Mental Deficiency Act of 1913.

Mr. Bevan the Minister of Health, informed the Parliament, that under the Lunacy and Mental Treatment Acts more than 20.000 were held in institutions in the beginning of 1945. And he added, that “A considerable proportion of these patients require only to be looked after; but those needing treatment receive it from the medical officers of the institution.”

The bill and all of its regulations were in full force at the time the United Nations and the Council of Europe introduced international human rights bills.

Eugenics in Denmark

Across the North Sea, Denmark – as the first country in Europe – enacted eugenics-based sterilization legislation, as a pilot law in 1929. The law was implemented by the Social Democratic government, with K.K. Steincke, minister of justice and later of social affairs, leading the effort.

The eugenic belief and concept went further than coercive sterilization. It influenced many aspects of social policy. In the 1920s and 1930s, when eugenics became a prerequisite and an integral part of the social development model in Denmark, more and more authors expressed the wish that even non-dangerous mentally disordered persons in some cases should be forcibly admitted to a mental hospital (asylum).

The driving force behind this idea was not a concern for the individual, but a concern for society. The renown Public Prosecutor of the Supreme Court, Otto Schlegel, noted in an article in the Weekly Journal of the Judiciary, that all authors, except one, thought that, “the possibility of compulsory hospitalisation should also be open to some extent to persons who are probably not dangerous but who cannot act in the outside world, the troublesome insane whose behaviour threatens to destroy or scandalize their relatives. Curative considerations have also been thought to justify compulsory hospitalisation in certain cases.”

Thus, the Danish Insanity Act of 1938 introduced the possibility of detaining non-dangerous insane persons. It was not a compassionate concern or an idea of helping people in need that led to the introduction of this possibility in legislation, but an idea of a society in which certain mentally disordered and “troublesome” elements had no place.

Eugenics policies exempted in the European Convention on Human Rights

It is in the light of this widespread acceptance of eugenics as an integral part of the social policy for population control that one has to view the efforts of the representatives of the United Kingdom, Denmark and Sweden in the process of formulating the European Convention of Human Rights drafting process suggested and included an exemption clause, that would authorize the government’s policy to segregate and lock up “persons of unsound mind, alcoholic or drug addicts and vagrants”.