I would like to illustrate my point by outlining the contributions to the idea and practice of Muslim-Christian dialogue made by two key individuals in recent Turkish history. Long before the Second Vatican Council, Bediuzzaman Said Nursi (1876-1960), one of the most influential Muslim thinkers of the 20th Century, advocated a dialogue between true Muslims and true Christians. The earliest statement of Said Nursi concerning the need for dialogue between Muslims and Christians dates from 1911, more than 50 years before the Council document, Nostra aetate.

Said Nursi was led to his view about the need for Muslim-Christian dialogue from his analysis of society in his day. He considered that the dominant challenge to faith in the modern age lay in the secular approach to life promoted by the West. He felt that modern secularism had two faces. On the one hand, there was communism that explicitly denied God’s existence and consciously fought against the place of religion in society. On the other, there was the secularism of modern capitalist systems which did not deny God’s existence, but simply ignored the question of God and promoted a consumerist, materialist way of life as if there were no God or as though God had no moral will for humankind. In both types of secular society, some individuals might make a personal, private choice to follow a religious path, but religion should have nothing to say about politics, economics or the organization of society.

Said Nursi held that in the situation of this modern world, religious believers – Christian as well as Muslim – face a similar struggle, that is, the challenge to lead a life of faith in which the purpose of human life is to worship God and to love others in obedience to God’s will, and to lead this life of faith in a world whose political, economic and social spheres are often dominated either by a militant atheism, such as that of communism, or by a practical atheism, where God is simply ignored, forgotten, or considered irrelevant.

Said Nursi insists that the threat posed by modern secularism to a living faith in God is real and that believers must truly struggle to defend the centrality of God’s will in everyday life, but he does not advocate violence to pursue this goal. He says that the most important need today is for the greatest struggle, the jihad al-akbar of which the Qur’an speaks. This is the interior effort to bring every aspect of one’s life into submission to God’s will. As he explained in his famous Damascus Sermon, one element of this greatest struggle is the necessity of acknowledging and overcoming one’s own weaknesses and those of one’s nation. Too often, he says, believers are tempted to blame their problems on others when the real fault lies in themselves – the dishonesty, corruption, hypocrisy and favoritism that characterize many so-called “religious” societies.

He further advocates the struggle of speech, kalam, what might be called a critical dialogue aimed at convincing others of the need to submit one’s life to God’s will. Where Said Nursi is far ahead of his time is that he foresees that in this struggle to carry on a critical dialogue with modern society Muslims should not act alone but must work together with those he calls “true Christians,” in other words, Christians not in name only, but those who have interiorized the message which Christ brought, who practice their faith, and who are open and willing to cooperate with Muslims.

In contrast to the popular way in which many Muslims of his day looked at things, Said Nursi holds Muslims must not say that Christians are the enemy. Rather, Muslims and Christians have three common enemies that they have to face together: ignorance, poverty, dissension. In short, he sees the need for dialogue as arising from the challenges posed by secular society to Muslims and Christians and that dialogue should lead to a common stand favoring education, including ethical and spiritual formation to oppose the evil of ignorance, cooperation in development and welfare projects to oppose the evil of poverty, and efforts to unity and solidarity to oppose the enemy of dissension, factionalism, and polarization.

Said Nursi still hopes that before the end of time true Christianity will eventually be transformed into a form of Islam, but the differences that exist today between Islam and Christianity must not be considered obstacles to Muslim-Christian cooperation in facing the challenges of modern life. In fact, near the end of his life, in 1953, Said Nursi paid a visit in Istanbul to the Ecumenical Patriarch of the Orthodox Church to encourage Muslim-Christian dialogue. A few years earlier, in 1951, he sent a collection of his writings to Pope Pius XII, who acknowledged the gift with a handwritten note.

The particular talent of Said Nursi was his ability to interpret the Qur’anic teaching in a such way that it could be applied by modern Muslims to situations of modern life. His voluminous writings which have been gathered together into the Risale-e-Nur the Message of Light express the need for a revitalization of society by the practice of everyday virtues like labor, mutual assistance, self-awareness, and moderation in possessions and deportment.

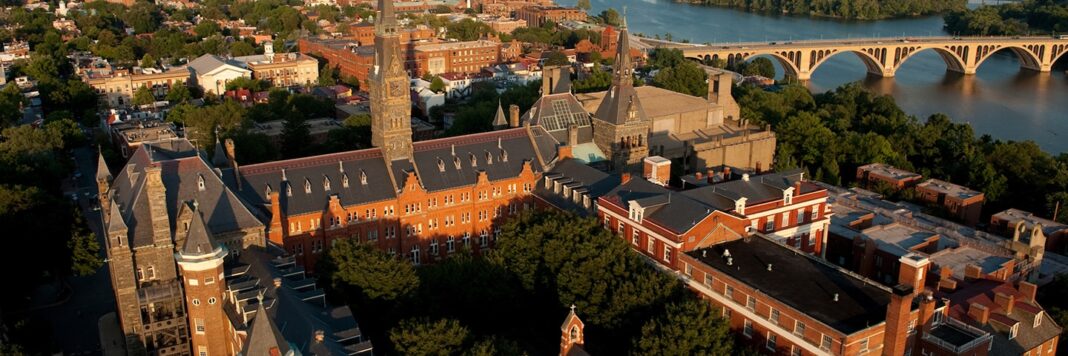

Note about the author: Father Thomas Michel, S.J., is a visiting professor at the Pontifical Institute for Arabic and Islamic Studies in Rome. He previously taught theology at Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service in Qatar and was a senior fellow with Georgetown’s Alwaleed Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding and Woodstock Theological Center. Michel has also served on the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, leading the office for engagement with Islam, as well as headed the interreligious dialogue offices of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences and the Jesuit secretariat in Rome. Ordained in 1967, he joined the Jesuits in 1971 and subsequently earned a doctorate in Arabic and Islamic studies from the University of Chicago.

Photo: The Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.