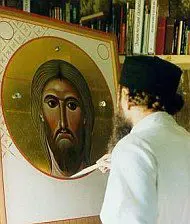

Archimandrite Zinon (Theodore) is the most famous icon painter of the Russian Orthodox Church and his works – murals, icons, miniatures are known throughout the Orthodox world. In 1992, he worked in the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, and in 1993, he led the icon painting activities in the St. Danilov Monastery, related to the 1000th anniversary of the conversion of Russia. In 1995, he was awarded a state prize, thus becoming the first Orthodox painter to receive state recognition in Russia. Then he worked in Pskov, in the New Valaam Monastery, in the Sheveton Monastery in Belgium, in Vienna, in Batumi (Georgia) and in many other places. He writes the temple in the Moscow metro station “Semkhoz”, erected on the place where priest Alexander Men was killed.

In 1994, the Pskov Museum of Local Lore handed over the building of the ancient Spaso-Mirozhki Monastery to the Russian Church, with the condition that an icon-painting school be organized here under the leadership of archim. Zinon. Gradually, the small brotherhood rebuilt the monastery and the school began its activities. The fame of archim. Zinon attracts there icon painters not only from Russia, but also from abroad. In 1997, a group of Italian artists worked at the school, including Catholic priests. Archim. Zinon allowed the guests to celebrate a Catholic mass in one of the chapels of the monastery, which had not yet been consecrated, and at the end of the service he received communion from them. A little later, the case gained publicity and archim. Zenon was placed under interdiction (that is, he had no right to serve) by Pskov Metropolitan Eusebius, and two monks from his monastery were excommunicated. The banning of the famous icon painter caused a violent reaction in Russia – many admirers of his work spoke out in his defense. At that time, Father Zinon’s personality was already iconic in Russian society, and his influence on the theology of the icon considerable. The monastery was closed, the brotherhood dispersed, and some of his works in the Pskov temples and monasteries were destroyed. Archim. Zinon retired to a small village, right on the border with Estonia, where he continued to work actively. In February 2002, the Russian Patriarch Alexy II removed from him all disciplinary prohibitions, and above all the prohibition to work as a priest. In 2006, with the permission of the patriarch, he went to Vienna and worked in the diocese of Bishop Hilarion Alfeev, where he wrote the Nikolaev church until September of that year. At the moment archim. Zinon worked on Mount Athos, where, at the invitation of the Simonopetra monastery, he inscribed one of the monastery’s temples.

Besides icon painter, archim. Zinon is also known for his works in the field of the theology of the icon, and among his most famous books is the “Discourses of the Icon Painter”.

To understand the meaning of Orthodox icon veneration, it is good to see how each icon was born. Invaluable helpers in this endeavor are the lives of the saints. Today it is widely believed that the Church creates an icon of someone only after his canonization. In fact, the first official canonization in Byzantium took place only in the 14th century and it was about St. Gregory Palamas. He was declared a saint by Patriarch Philoteus Kokinos a few years after his death, and of course veneration for him was already a fact in Thessaloniki and the region. Which does not mean that the Church did not glorify saints before, nor that it did not inscribe them on icons. Until then, and for many centuries after, the only criterion for someone’s holiness was the unanimous veneration of the clergy and people, who testified with this unanimity to his orthodoxy and his pious life.

General information about the development of icon painting

Every saint has been subjected, at certain periods of his life, to persecution, challenge and denial, not only by secular authorities or open God-fighters (as perhaps we wish, to make it easier for us to find our way), but also by pious people, by ecclesiastical authority, and sometimes even by other saints.

After the death of the saint, whose sanctity was repeatedly demonstrated by miracles during his life and after his death, tropars for him appeared, included in the church service. The beginning of his ecclesiastical glorification are the so-called panagiri from Greek – great holidays dedicated to a deceased saint, which were annual and sometimes lasted a week… The more beloved the saint was, the more his images were on icons and murals.

There have been cases when a patriarch or other representative of the highest authority tried to ban someone’s veneration as a saint and, accordingly, to ban his icons, but they ended in failure. For example, in the 11th century, a senior official of the Patriarch of Constantinople tried to prohibit St. Simeon the New Theologian from organizing annual church celebrations in memory of his spiritual father, St. Simeon the Studite. The reason is that he considered St. Simeon the Studite to be a sinful man and not a saint. He managed to convince the patriarch and other senior church officials of this, and St. Simeon the New Theologian was subjected to persecution. Church holidays in memory of St. Simeon the Studite were banned, his icons and wall paintings were destroyed, and St. Simeon the New Theologian himself was exiled. They left him only the icon painted by himself, as a memory of his teacher, but deleted the word “saint” from it. After years of exile, when the prayerful reverence for St. Simeon the Studite did not decrease, but on the contrary, increased, St. Simeon the New Theologian was rehabilitated, and the church holidays in honor of his spiritual father were restored in Constantinople with even greater splendor than before .

Most icons were created spontaneously by grateful Christians during the saint’s lifetime or shortly thereafter. Here, for example, St. John Chrysostom, in his eulogy for Meletius, bishop of Antioch, delivered five years after his death, says that the believers in Antioch loved their bishop so much that they baptized their children with his name, Meletius. They invoked him in their prayers as an intercessor before God and thus removed every passion and sinful thought. His name was heard everywhere – in the market, in the square, in the field. But the Christians, continued St. John Chrysostom, loved not only his name, but also his holy body. Therefore they painted his image on the walls of their homes, stamped his face on rings, put his image in various places, so that they not only heard his name, but also comforted themselves with his image because of his sleep.

An example of a saint depicted during his lifetime is St. Simeon the Pillar, who lived in the 5th century in Syria. Theodoret of Kirsky, who wrote his Church History 15 years before the saint’s death (459), says that his fame was so great that people flocked to him from all over Christendom. And the artisans in Rome had hung small icons of him in front of the doors of their workshops to guard and protect them.

St. Simeon Novi lived in the 6th century again in Syria. He was known for his great miracles. Several instances of his depiction of icons are described in his biography. A woman named Theotecna separated from her husband and visited the saint to share her problem with him. Through his prayers, the couple got together again and had a child, which they brought to the saint for a blessing. When she returned home, she hung an icon of the saint in the inner rooms of her home. The biographer does not say whether she commissioned it to be painted or bought it ready-made somewhere. This icon was miraculous and through it many possessed and sick people were healed. Another case from the same life is that of a craftsman from Antioch who suffered for many years from demonic worries. Through the prayers of the saint, he was healed and out of gratitude hung his icon in a prominent place in the agora and above the door of his workshop. However, the saint was not loved in the city, because he had recently denounced its inhabitants for idolatry – therefore a commotion arose and many wanted to destroy his icon. Without explaining the details, the biographer says that the crowd dispersed after “a believing woman, a harlot, who at that hour was filled with the Holy Spirit” denounced them in a loud voice for their impiety and idolatry.

Saint Theodore of Syceot, bishop of Anastasiopolis, died in the early 7th century. Monks from his monastery, together with the abbot, decided to secretly paint his image on an icon in order to have it in their monastery as a memory and blessing. For this purpose, they called an artist, who observed and iconographed the saint through an opening. Before he left, the monks showed Saint Theodore his image. He joked if this was the most valuable thing they found to steal, smiled and blessed the icon.

And so behind the creation of each icon there was a personal story, a personal contact with a certain saint, whose sanctity was witnessed by the love and trust of the people… A woman receives help from a saint and because it is unlikely that she will ever be able to go to him again , orders his image to be painted to take to his home. Somehow, naturally, the prayer contact continued in the home and the believer did not even think that he was praying to the image, and not to the saint, the living memory of which he keeps in his memory… Naturally, everything can be profaned. This also happens with icons – in the later centuries, on the eve of the iconoclastic crisis, many believers began to look at them as amulets, having their power in themselves. The sense of a personal prayerful relationship in love with the depicted person is lost and replaced by a sense of awe at the supernatural powers of the icon as an object. The love between two persons – the person praying and the saint – is replaced by a consumer attitude towards the icon, from which the believer seeks some benefit that he could not naturally receive. This attitude gave birth to various non-Orthodox practices in spirit and, along with other political and cultural reasons, gave rise to the outbreak of iconoclasm disputes.