Researchers have studied the largest bacteria ever discovered: it has surprisingly complex cells.

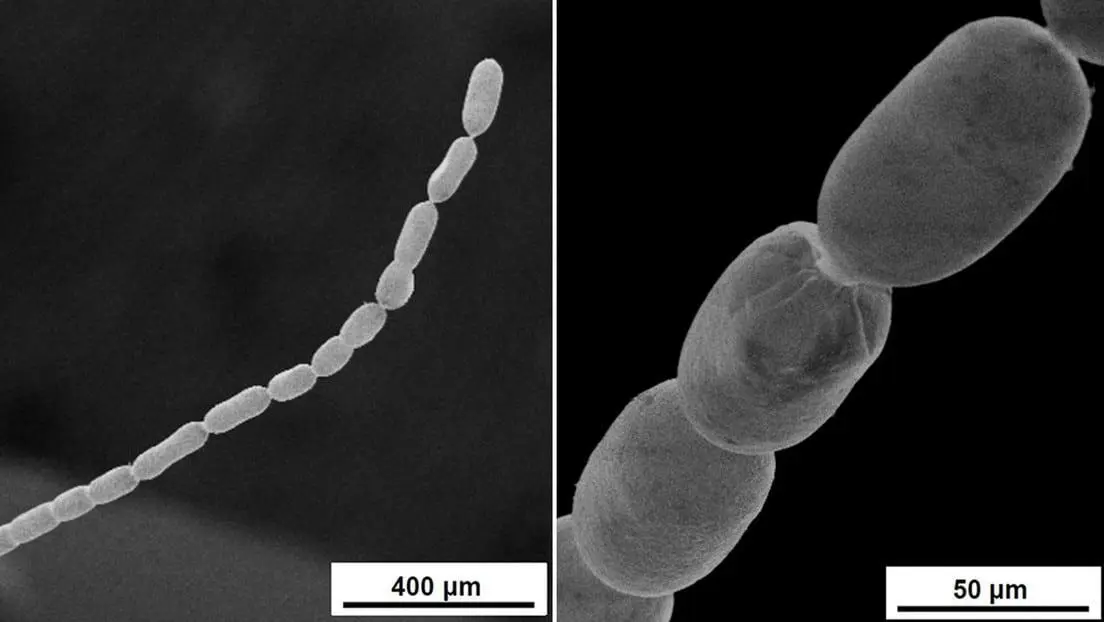

By definition, microbes are so small that they can only be observed with a microscope. But a recently described bacterium living in Caribbean mangroves is different. A filamentous single cell is visible to the naked eye, it grows up to 2 cm – the length of a peanut. This is 5,000 times more than most microbes.

Moreover, this microbe has a huge genome that does not float inside the cell, like other bacteria, but is located in the membrane. This is typical for much more complex cells, for example, those that are in the human body.

Researchers have long divided organisms into two groups: prokaryotes, which are bacteria and single-celled microbes, and eukaryotes, which are everything from yeast to most forms of multicellular organisms, including humans. Prokaryotes have free floating DNA, while eukaryotes have it in the nucleus.

But a newly discovered microbe blurs the line between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. About 10 years ago, Olivier Gros, a marine biologist at the University of the French Antilles, Pointe-à-Pitre, stumbled upon a strange organism that grows on the surface of decaying mangrove leaves. It wasn’t until 5 years later that he and his colleagues realized that these organisms were actually bacteria.

Her genome was huge, with 11 million bases and 11,000 genes. Typically, bacterial genomes average about 4 million bases and about 3,900 genes.

Like the microbe found in Namibia, the new mangrove bacterium also has a huge sac—presumably of water—that takes up 73% of its total volume. That similarity and a genetic analysis led the research team to place it in the same genus as most of the other microbial giants and propose calling it Thiomargarita magnifica.

“What an excellent name!” says Andrew Steen, a bioinformatician at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, who studies how microorganisms affect geochemical cycles. “Reading about it makes me feel exactly the same way as when I hear about an enormous dinosaur, or some celestial structure that is impossibly large or hot or cold or dense or weird in some way.”

The largest T. magnifica cell Volland found was 2 centimeters tall, but Carvalho thinks that if not trampled, eaten, blown by wind, or washed away by a wave, they could grow even bigger.

Photo: Thiomargarita magnifica