“The Most Divine One is incomprehensible: for the verses of the bookless, fishermen are wise, suffocating with a word, and from the deep night, withdrawing people are countless, by the brilliance of the Spirit.” (From the third ode of the second canon of the Matins of Pentecost)

Any text has many features in the choice of words, in the construction of phrases, in its very content; features of the text – a manifestation of the characteristics of the personality of the writer.

Since ancient times, the saints have been telling us how the words of Scripture reveal the character of the spirit of the writer. Yes, st. Irenaeus of Lyons, interpreting the expression about the unbelievers – “whose minds of this world God has blinded” (2 Cor. 4, 4), says that in order to understand the meaning, one must take into account the way of expression characteristic of Paul: it spirit, makes movements in words”[1]. But at the same time, “man asks, and the Spirit answers.”

However, it would be hasty to conclude from this that we can explain any feature of the text of Scripture at our will by the properties of the personality of the clergyman. After all, on the other hand, everything that is contained in Scripture is the words of the Spirit. This is expressed with particular force by St. Theodore the Studite, when addressing the monastic scribes:

“Be strong scribes, laboring in calligraphy, for you are the inscribers of the laws of God and the scribes of the words of the Spirit, passing books not only to the present, but also to subsequent generations”[2].

Before starting a discussion of patristic thoughts about the inspiration of Scripture, we would like to make an aside remark. The development of historical thought is sometimes a challenge for a Christian. When the prevailing scientific hypotheses become incompatible with the telling of the Sacred History, there is a great temptation to “make something up”. A typical example in this regard is provided by the recent paper of the Pontifical Biblical Commission “Inspiration and Truth of the Holy Scriptures” (2014). About the biblical story about the return of the Jews to the land of Palestine, it says that “in fact, in a real war, the walls of the city do not collapse at the sound of trumpets (Josh. 6, 20)” and that this and similar passages of Scripture “should be considered as a kind of parable, which brings characters with symbolic meaning onto the stage”[3].

Can an Orthodox adhere to such a point of view? The Church has not, to our knowledge, made any recent determinations about the text of Scripture; however, we have at our disposal the authoritative message of the Eastern Patriarchs of 1723, whose text was also approved by the Russian Synod. There we read the following:

“We believe that Divine and Holy Scripture is inspired by God; therefore, we must believe it unquestioningly, and, moreover, not in our own way, but precisely as the Catholic Church has explained and betrayed it. <…> Since the Culprit of both is the same Holy Spirit, it makes no difference whether one learns from the Scriptures or from the Universal Church. A person who speaks for himself can sin, deceive and be deceived; but the Universal Church, since she has never spoken and does not speak from herself, but from the Spirit of God (Which she has unceasingly and will have as her Teacher until eternity), cannot in any way sin, nor deceive, nor be deceived; but, like Divine Scripture, it is infallible and has everlasting importance”[4].

If we agree with this, then it is not so easy to take the point of view of the Pontifical Biblical Commission. Indeed, in order to declare the historical narratives of Scripture to be parables and allegories, one must find interpretations of the holy fathers, and not just talking about the symbolic meaning of this text, but declaring it a parable – that is, a symbolic, but in reality, history that did not take place. Only then can such an interpretation be considered “transmitted” by the Church with at least some degree of meaningfulness.

For the same reason, the hopes of some jurisdictionally Orthodox writers to avoid conflict with the prevailing scientific notions by emphasizing the human elements of Scripture are also futile. Any attempt to declare Scripture erroneous at least in one particular place, as it seems to us, will not pass through the “sieve” of patristic interpretations.

Any attempt to declare Scripture erroneous at least in one particular place will not pass through the “sieve” of patristic interpretations.

Before proceeding to the exposition of the patristic testimonies, let us briefly say what we will try to substantiate.

1. Not only dogmatic and moral passages of Scripture are infallible, but even individual “unessential” verses are the work of the Holy Spirit, and not just human authors.

2. Scripture is inspired not only at the level of general meaning, but also of textual expression.

3. The manner of expression and the way of conveying thoughts in Scripture is not only the work of the clergyman; The Holy Spirit gives the gift of wisdom and eloquence, which is poured throughout the text of Scripture.

4. Even individual words and prepositions of Scripture are not without the care of the Holy Spirit.

Today, unfortunately, one can often hear that these positions are “fundamentalist”, almost Protestant. But, as we shall see below, they have their basis in the Holy Tradition of the Church.

Single iota

If we assume that only a certain universal non-verbal sense of Scripture is inspired by God, expressed exclusively by human efforts in different languages, then we should expect that the holy fathers will not resort to such interpretations, the very existence of which depends on the language of Scripture.

But in fact, such interpretations, although not frequent, are quite common in patristic writings.

St. Maximus the Confessor, explaining the expression about two birds sold for an assarium, writes that “an assarium is ten nummi, the number ten means the letter iota, and this letter is the first in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ”[5].

The number 10 is indeed represented by the Greek letter iota and the Hebrew letter iodine. But already in Latin, “I” means a unit (and, by the way, St. Maximus is one of the few Eastern saints who was strongly associated with the Latin West, still Orthodox in those centuries); translate the interpretation of prp. Maxim in Latin (as well as in English, say) is impossible with the preservation of meaning: you have to explain to the reader what is at stake.

In the same way, St. Basil the Great, in order to reveal the meaning of the Scripture narrative about the creation of the world, turned to the Syriac language, as closer to Hebrew[6]. Moreover, he writes that “the Syrian language is more expressive and, by affinity with Hebrew, comes somewhat closer to the meaning of Scripture.”

This is indicative. As you can see, St. Basil did not consider the meaning of Scripture to be something invariant, existing regardless of language and forms of expression, but connected the meaning of Scripture with how it is revealed in a particular word.

Blessed Augustine writes about translations of Scripture into Latin:

“The reader must either strive to understand the languages from which Scripture is transcribed into Latin, or must have more literal translations”[7].

At the same time, the saint was well aware that, from the point of view of taste and style, literal translations look inelegant, but he considered them preferable – “because they can show the reader the correctness or error of their not so much words as thoughts, which were kept in translations.”

However, the literal translation is not a panacea. For excessive literalism in translation, which destroys the clarity of the text, the translation of Akila by St. Epiphanius of Cyprus[8], who prefers the translation of 70 interpreters.

It should also be noted that even the centuries-old liturgical use of one or another translation did not stop the holy interpreters from clarifying the meaning of the meaning of Scripture from the original text. Yes, St. Theophan the Recluse corrected the understanding of the Slavic Apostle in Greek[9], and schmch. Hilarion (Troitsky) resorted to the analysis of the Hebrew text[10], extracting meaning from the coincidence of Hebrew words in those passages of Scripture where different ones are used in the Greek text (“among 70 interpreters”).

We would like to emphasize that recognizing the existence of some basic, referential text of Scripture does not mean recognizing the priority of the current Hebrew text (Masoretic edition) of the Old Testament over the Greek translation of 70 interpreters. It only means that the words of Scripture should be considered in their entirety of meaning, including the additional meanings of the original text (in St. Basil) and sometimes even the lettering of names (in St. Maximus) – and that one should not reduce the many-sided full meaning of Scripture to one only the general idea of what was written.

The words of Scripture must be considered in their entirety, including the additional meanings of the original text.

The fact that the Holy Spirit generally takes care of the words of Scripture, as it seems to us, is clear from the most ancient tradition about the translation of the Old Testament from Hebrew into Greek. Excellent storytelling ssmch. Irenaeus of Lyons about 70 interpreters deserves to be quoted in full:

“Wishing to test them separately and fearing that by mutual agreement they would not hide the truth contained in the scriptures through the translation, he separated them from each other and ordered everyone to translate the same scripture; he did the same with regard to all (other) books. When they gathered together at Ptolemy and compared their translations, God was glorified and the writings were recognized as truly Divine, because they all read the same thing in the same words and with the same names from beginning to end, so that the Gentiles present realized that the Scriptures were translated by the inspiration of God. And there is nothing surprising in the fact that God did it. He, who, when during the captivity of the people by Nebuchadnezzar the Scriptures were damaged and after 70 years the Jews returned to their country, after, in the time of Artharxerxes, the Persian king, inspired Ezra, a priest from the tribe of Levi, to restore all the words of the former prophets and renew to the people the statute of Moses.

When thus the Scriptures were translated with such fidelity and with God’s grace, and when from them God prepared and formed our faith in His Son, preserving for us the Scriptures intact in Egypt … “[11].

Thus, it seems clear that, on the one hand, God has care about the individual words of the Scriptures, on the other hand, that the translation of the seventy was inspired in a very special way.

With deep expressiveness, St. John Chrysostom in one of his sermons. Its idea is visible even from the title – “That should not leave without attention neither time nor even a single letter of the Divine Scriptures”; St. John says this:

“It was not in vain that I said this and spread about it not without reason, but because there are treacherous people who, having taken the Divine books in their hands and seeing the count of time or the enumeration of names, immediately leave them and say to those who reproach them: there are only names here, and there is nothing useful. What are you saying? God speaks, and you dare to say that there is nothing useful in what has been said? If you see only one simple inscription, then tell me, will you not stop at it with attention and begin to explore the wealth contained in it? But what do I say about times, names and inscriptions? See what power the addition of a single letter has, and stop neglecting whole names. Our Patriarch Abraham (indeed, he belongs to us rather than to the Jews) was first called Abram, which in translation means: “stranger”; and then, being renamed Abraham, he became the “father of all nations”; the addition of one letter gave the righteous man such an advantage. Just as kings give golden tables to their governors as a sign of power, so God then gave this letter to the righteous as a sign of honor.

This does not only apply to names. So, the 318 people with whom Abraham went out to opponents are also interpreted symbolically: the lettering of 318 (τίη) in Greek begins with the letter “tau”, which forms a cross, and the subsequent iota and eta represent the name of the Lord Jesus (Ἰησοῦς). The remarkable unity of ancient and modern interpreters here shows the right. John of Kronstadt, referring in this matter to Clement of Alexandria[13].

Blessed Jerome also speaks of the meaning of the very letters of Scripture:

“Individual words, syllables and points in the Holy Scriptures are full of meaning, therefore we are more likely to be reproached for word production and word combination than for damaging the meaning”[14].

St. Jerome is quite consistent in his theory that texts should be translated according to their meaning. However, Holy Scripture has many more levels of meaning than human texts; because St. Jerome retains meaning, even by making his speech ugly, but retaining the “words, syllables” – perhaps we would say “morphemes” – and the “points” of Scripture, because they are also full of meaning.

However, if this is the task facing the translator of Scripture, then when using it, it is quite possible to take only the right part, the right level of meaning, and quote it paraphrastically, if it is appropriate. It seems to us that this is exactly what we are talking about when, in his letter to Pammachius about the best way to translate, Blessed Jerome writes that one should not translate literally[15].

After that, Blessed Jerome cites a number of places in the New Testament, where the texts of the Old are retold paraphrastically or allegorically, – in general, not by direct quotation. By this Blessed Jerome defends his translation of the letter of St. Epiphanius of Cyprus, produced by him not literally, but in meaning.

This Jerome idea, unfortunately, is often interpreted quite falsely – in the sense that Blessed Jerome did not at all attach weight to the words of Holy Scripture, if the thought is restrained. Meanwhile, the saint wants to say that when only a general meaning is needed, there is no need to quote the text word for word, a paraphrase is enough. However, Jerome does not in any way claim that in Scripture only this general meaning exists, or that under other circumstances a literal translation cannot be required. In the same letter (!) Jerome says:

“For I not only confess, but also freely declare that in translation from Greek, except for Holy Scripture, in which the arrangement of words is a mystery, I convey not word for word, but thought for thought.”

It should be noted, by the way, that among the opponents of St. Jerome, who insisted on a literal translation even of the letters of St. Epiphanius, there was at least one saint – St. Melania Roman, who is mentioned by Jerome himself as one of the instigators of controversy.

A modern scholar thus sums up the position of Blessed Jerome regarding the inspiration of Scripture:

“The Presbyter of Bethlehem regards all the books of the Bible as “one Book” (unus liber), a single creation of the Holy Spirit, since they are all written by the same Holy Spirit. Like many other early exegetes, he saw the inspired writers of the Bible as instruments (quasi organum) through which the Holy Spirit spoke and acted. Having received Him, the prophets and apostles spoke “on behalf of God.” The whole Bible was written “under the dictation (dictante) of the Holy Spirit”, and therefore in it “even individual words, syllables, lines, dots are filled with meaning”. God Himself teaches through His Scripture, therefore it has indisputable Divine authority; it is always true and cannot contradict itself; if we meet in it two opposite statements, then, as Blazh believes. Jerome, one should consider that both of them are true, and look for the possibility to get it right.”[16]

Even suggestions are worth considering

With such an opinion about the letters of Holy Scripture, the Fathers, of course, even more decisively begin to interpret individual words, including prepositions and demonstrative pronouns.

So, for example, St. Basil discussed with the Eunomians the question of why Scripture uses the expression “in the Spirit” more often than “with the Spirit.” The very chapter of his work on this is called “On the fact that Scripture uses the syllable ‟v” instead of the syllable ‟s”, and also that the syllable ‟i” is equivalent to the syllable ‟s” [17].

It is curious that at the same time, in order to discuss the text of the Apostle Paul, St. Basil draws on examples from the Psalms. Thus, the stylistic unity of Scripture at the level of prepositions seems self-evident and does not need to be proved to the saint: that is, if the preposition “in” elevates to a greater height than “with” in the Old Testament, then the same can be expected in the New. It seems that such stylistic unity cannot be attributed to the commonality of the artistic vision of the priests, but rather to the unity of the Spirit who spoke through the apostles and prophets.

Also curious is the general remark of St. Vasily on the topic of research into which he entered: “to disassemble even the syllables themselves does not mean moving away from the goal.”

Dmitry Leonardov, analyzing the sermons of St. John Chrysostom, notes: “In the works of Chrysostom there are many places where the divine inspiration of particular words of the biblical text is affirmed”[18], and we are talking not only about significant words, but also about introductory conjunctions such as the word “when”. True, the author of the study draws a somewhat unusual conclusion from these words. Leonardov writes:

“We must also not forget that Chrysostom recognizes the difference in the degrees of inspiration of St. writers. In accordance with these degrees, the volume of the actual human work of St. writer in compiling this or that St. books”,

And

“he insists only on the deep meaning in the Bible of every word, syllable and letter, but not at all on their extraordinary, supernatural origin.”

Can we agree with this conclusion? Let’s take a closer look at what St. John Chrysostom.

Just before the words: “Look what power the addition of a single letter has, and stop neglecting whole names,” the saint warns menacingly:

“God speaks, and you dare to say that there is nothing useful in what has been said?”

And the very view that in every word, syllable and letter of Scripture “the sea of Divine thought is poured”, but this happened “naturally” (if not due to “supernatural origin”), seems very strange. In fact, an attempt to attribute St. John, the idea of the greater and lesser Divinity of the Scriptures cannot in any way be considered successful, since St. John repeatedly says the opposite. For example:

“Let us therefore not neglect those thoughts of the Scriptures, which are considered unimportant, because they too are from the grace of the Spirit; the grace of the Spirit is never small and meager, but great, amazing and worthy of the bounty of the Giver. <…> And this, i.e., that it was not only said, but set out in writing and transmitted through the epistle to all future generations, is not the work of Paul, but the grace of the Spirit ”[19].

The very idea that Scripture, even in individual words, is the work of the Omniscient Spirit dates back to the very early days of Christianity and, apparently, is of apostolic origin. Yes, ssmch. Irenaeus of Lyon writes that the Evangelist Matthew could have said, “The birth of Jesus was like this,” but the Spirit said, “The birth of Christ was like that”[20].

Blessed Jerome[21] has a similarly high opinion of the choice of words in the Book of the Prophet Ezekiel, calling attention to “the elegance of Holy Scripture.”

“The Grace of Scripture”

The blessed one, being a translator, was aware of the stylistic difference between different priests. However, he attributed the apparent rudeness of speech found in Scripture, first of all, to the need to adapt to the language of the listeners: “due to deliberate adaptation to the edification of the common people”, but at the same time with the preservation of meaning for the “scientists”[22].

Above, we have already seen the review of schmch. Irenaeus on the peculiarities of the letter of the Apostle Paul. However, the same schmch. Irenaeus puts up a decisive barrier when discussing the suggestion that, at the content level, the text of Scripture may contain an adaptation to the thinking of the listeners: only the most empty sophists can argue that “the Lord and the Apostles did not conduct the work of teaching according to the truth, but hypocritically and adapting to the acceptability of each ”, in fact, “The apostles sent to find the lost, to provide insight to those who have not seen and to heal the sick, of course, spoke to them not according to their real opinion, but according to the revelation of the Truth”[23].

The beauty of the word of Scripture has a supernatural foundation, pouring out from Him Who creates great minds.

Blessed Augustine, by the way, in some cases found it possible to support barbarisms in the translation of Scripture, rather than obscure its meaning[24]. At the same time, Blessed Augustine does not at all doubt the eloquence of Scripture, and the beauty of the word of Scripture has a supernatural basis, pouring out from Him Who creates great minds, and concludes:

“For this reason, I boldly recognize our canonical Writers and Teachers not only as wise, but also eloquent in relation to such a kind of oratory, which was completely befitting of persons inspired by God.”

The fact that the beauty of the words of Scripture is based on Divine grace, although the authors do not make beauty an end in itself, unlike human sages, is also written by St. John Chrysostom: Scripture “in itself has divine grace, which imparts splendor and beauty to its words”[25].

It was left to St. Photius of Constantinople, one of the most educated people of his era. In his letter to George, Metropolitan of Nicomedia, St. Photius draws attention to the elegance and beauty of what Paul said, and emphasizes that it is not about the content (“teaching and faith”), but about the rhetorical ability of the apostle (“strength and power of speech”)[26].

St. Photius contrasts the purity of Paul’s words with the indistinctness of Plato’s turns, noticing also the amazing combination of greatness with the clarity of Paul’s speech. It should also be noted that St. Photius does not attribute these abilities to Paul himself because of his education or intellectual level. On the contrary, he notes that all the apostles were simple and ignorant people, “more mute than the fish they caught” – but God showed them lacking “nothing of the wisdom of man.”

St. Photius insists that the Apostle Paul possessed all varieties of verbal skill, and, despite the ignorance of his language, this was the result of “Divine power perfected in weakness”, its “moderate outflow” (apparently, St. Photius implies that Divine power is more obvious in the very the content of the messages than in the form – but also in the form), the fruit not of studies, but of supernatural inspiration:

Thus, the style of the epistles of the great Paul, embodying all varieties of verbal skill and colored with appropriate and suitable figures, in the eyes of prudent people is worthy to take the place of a type, and a model, and an object for imitation, and it is unjust to attribute to it the imitation of others. After all, it is not easy to find whom he repeated, because Paul’s speeches are not the fruit of studies, but of supernatural inspiration, a wealth of wisdom, a pure and transparent source of truth, flowing with saving pleasure. This is a kind of small reflection of a formidable lightning from above, beating from the apostolic lips, this is a kind of moderate outflow of Divine power accomplished in weakness, irrigating the whole world, this is an indisputable evidence of grace acting in clay vessels (oh, terrible and extraordinary mysteries!), wisdom pouring from the unlearned language, from uneducated lips – the measure of eloquence, from ignorant lips – rhetorical art.

Holy Scripture is not only eloquent in itself, but also becomes the basis of truly church rhetoric.

The fact that Scripture, even in relation to the manner of speech, takes the place of “a model and an object for imitation” reminds one of the rights. John of Kronstadt, noting that Holy Scripture is not only eloquent in itself, but also becomes the basis of truly church rhetoric:

“Holy Scripture is a shining light in the dark place of this world. How many it enlightened! How many people borrowed the power of their word from him! All the great preachers of the Church, all the creators of spiritual creations, in which we find so much delight, so much loftiness and beauty of the word, were formed by the Holy Scriptures”[27].

In all of the above, we deliberately did not touch on the question of how the writer of the inspired text is recorded, or on the degree of clarity of prophetic revelations and types for the prophet himself. It seems to us that the acuteness of the issue of the specific mechanics of receiving an inspired text will be removed if we agree that, according to the teachings of the holy fathers, the text of Scripture was unmistakable, full of meaning in every word and full of eloquence, which, if it was stylistically adapted to the listeners, remained – and still remains! – unquestionably faithful to the revealed truth.

Author: Stanislav Minkov, December 9, 2021, pravoslavie.ru

Notes:

[1] Irenaeus of Lyon, Hieromartyr. Refutation and refutation of false knowledge (Against heresies). Book 3. Chapter VII. An answer to an objection borrowed from St. Paul.

[2] Theodore the Studite, Rev. T.V.

[3] “Inspiration and Truth of Holy Scripture”

[4] Epistle of the Patriarchs of the Eastern Catholic Church (1723).

[5] St. Maximus various questions and selections from various chapters of perplexities.

[6] Basil the Great, saint. Conversations on the Six Days.

[7] Augustine the Blessed. Christian Science or Foundations of Hermeneutics and Church Eloquence.

[8] Creations of St. Epiphanius, Bishop of Cyprus. T. I-VI.

[9] Theophan the hermit, saint. About our duty to adhere to the translation of 70 interpreters.

[10] Hilarion Troitsky, Hieromartyr. Holy Scripture and the Church.

[11] Irenaeus of Lyon, Hieromartyr. Refutation and refutation of false knowledge (Against heresies).

[12] St. John Chrysostom. Conversation 2. To the words of the prophet Isaiah “in the year of the death of the king …”.

[13] Holy Righteous John of Kronstadt. Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew.

[14] Jerome the Blessed of Stridon, Rev. The doctrine of the inspiration of Holy Scripture.

[15] Jerome the Blessed of Stridon, Rev. Letter to Pammachius about the best method of translation.

[16] Redkova Irina Sergeevna. The image of the city in Western European exegesis of the XII century.

[17] Basil the Great, saint. About the Holy Spirit.

[18] Leonardov D.S. The teaching of St. John Chrysostom on the inspiration of the Bible.

[19] St. John Chrysostom. Conversations about statues.

[20] Irenaeus of Lyon, Hieromartyr. Refutation and refutation of false knowledge (Against heresies).

[21] Jerome the Blessed of Stridon, Rev. The doctrine of the inspiration of Holy Scripture.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Irenaeus of Lyon, Hieromartyr. Refutation and refutation of false knowledge (Against heresies).

[24] Augustine the Blessed. Christian Science or Foundations of Hermeneutics and Church Eloquence.

[25] St. John Chrysostom. Creations. Volume IV. Book 1. Conversation 37.

[26] Saint Photius, Patriarch of Constantinople. Commentary on the Gospel of John.

[27] Holy Righteous John of Kronstadt. A diary. Volume I. Book 2.

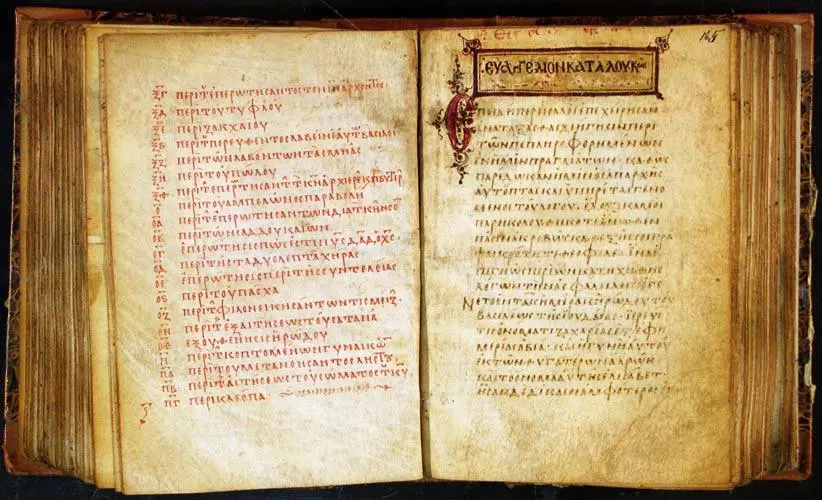

Photo: The Petersburg Codex (lat. Codex Petropolitanus; symbol: Π or 041) is an uncial manuscript of the 9th century in Greek containing the text of the four Gospels, on 350 parchment sheets (14.5 x 10.5 cm). The manuscript got its name from the place of its storage. The text on the sheet is arranged in one column with 21 lines in a column. The manuscript contains several lacunae (Matt 3:12-4:18; 19:12-20:3; John 8:6-39), totaling 77 verses. In the Gospel of Mark, the text of the manuscript reflects the Byzantine type of text, repeatedly similar to the text of the Codex Alexandrinus. The manuscript is assigned to the V category of Aland. The manuscript was found by Tischendorf in the east and brought back in 1859[2]. Currently, the manuscript is kept in the National Library of Russia (Gr. 34), in St. Petersburg.