By prof. A. P. Lopukhin

John, chapter 19. 1 – 16. Christ before Pilate. 17 – 29. The crucifixion of Jesus Christ. 30 – 42. The death and burial of Jesus Christ.

19:1. Then Pilate took Jesus and scourged Him.

19:2. And the soldiers, having woven a crown of thorns, put it on His head, and clothed Him with a purple robe,

19:3. and they said: Rejoice, King of the Jews! and they slapped Him.

(See Matt. 27:26ff. Mark 15:15ff.).

Complementing the accounts of the first evangelists about the flagellation of Christ, John presents this flagellation not as a punishment preceding, according to custom, the crucifixion, but as a means by which Pilate intended to satisfy the malice of the Jews against Christ.

19:4. Pilate went out again and said to them: behold, I am bringing Him out to you, so that you may know that I find no fault in Him.

Punishing Christ and bringing Him before the Jews with the marks of a beating on His face, with a crown of thorns and an ivy (cf. Matt. 27:28 – 29), Pilate showed them the complete failure of their accusations against Christ. “Can such a man be considered a contender for the king’s crown?” Pilate seemed to be saying. Pilate indeed finds no serious grounds for accusing Christ of the intentions attributed to Him.

19:5. Then Jesus went out with the crown of thorns and in a sackcloth. And Pilate said to them: here is the Man!

The words “Behold the Man!” can be understood in two ways. On the one hand, Pilate wanted with this exclamation to show that before the Jews stood an insignificant person, to whom only mockingly attempts to seize the royal power could be attributed, and on the other hand, he wanted to arouse in the people who were not completely fierce, compassion for Christ.

19:6. And when the high priests and servants saw Him, they cried out and said: Crucify Him, crucify Him! Pilate says to them: take him and crucify him, because I find no fault in him.

Nothing is said about how the common people gathered in front of the procurator’s palace reacted to this pitiful spectacle: the people were silent. But the “high priests and” their “servants” began to shout loudly that Pilate should crucify Christ (cf. John 18:40, where “all” who shout are described). Annoyed by their obstinacy, Pilate again mockingly suggested that the Jews should execute Christ themselves, knowing that they would not dare to do so.

19:7. The Jews answered him: we have a law, and according to our law He must die, because He made Himself the Son of God.

Then Christ’s enemies pointed out to Pilate a new ground on which they wanted Christ to be condemned to death: “He did,” i.e. “He called Himself the Son of God.” By this, the Jews wanted to say that in His conversations with them, Christ claimed equality with God, and this was a crime for which the Mosaic law provided for the death penalty (it was blasphemy or humiliation of God, Lev. 24:16).

19:8. When Pilate heard this word, he was even more afraid.

From the very beginning of the trial against Christ Pilate felt a certain fear of the Jews, whose fanaticism he knew well enough (Josephus, “The Jewish War”, XI, 9, 3). Now to this former fear was added a new superstitious fear of the Man, of whom Pilate had, of course, heard stories as a miracle-worker, and who had become an object of reverent veneration among many of the Jews.

19:9. And again he entered the praetorium and said to Jesus: Where are you from? But Jesus did not answer him.

Alarmed, he takes Christ back to the Praetorium and questions Him no longer as a representative of justice, but simply as a man in whom the heathen ideas about the gods who formerly came down to earth and lived among men have not died out. But Christ did not want to answer a man who was so indifferent to the truth (John 18:38), did not want to talk to him about His divine origin, since Pilate would not understand Him.

19:10. Pilate says to Him: do you not answer me? Don’t you know that I have power to crucify You, and I have power to let You go?

Pilate understood that Christ did not consider him worthy of conversation with Him, and with a feeling of insulted self-love he reminded Christ that He was in his hands.

19:11. Jesus answered: you would not have had any authority over Me, if it had not been given to you from above; therefore the one who betrayed Me to you has a greater sin.

But Christ answers him that he has no power to dispose of His destiny – it is up to Christ Himself to lay down His life and accept it back (John 10:17 et seq.; 12:28 et seq.). If Pilate now has the right to condemn Christ to death, it is because it is so decreed (“given”, i.e. appointed) “from above” or by God (ἄνωθεν, cf. John 3:27). In vain did Pilate boast of his right as procurator in the present case; in the case of Christ, he is a pitiful, characterless man, devoid of conscience, whom it was because of such inherent qualities that God allowed him to become the executioner of the Innocent Sufferer.

“greater sin is that.” Nevertheless, there is no justification whatsoever in Christ’s words to Pilate. He is also guilty, although his guilt is less than that of the one whom Christ handed over to Pilate. Condemning Christ, Pilate shows his low character, his corrupt nature, and although in doing his bloody deed he fulfills, without realizing it, the mysterious predestination of God’s will, yet he personally, as judge – guardian of justice, has betrayed his calling and is subject to condemnation because of this.

“the one who betrayed Me to you”. As for the Jewish people who handed Christ over to Pilate, and especially the high priest and the priests (cf. John 18:35: “Your people and the high priests delivered You to me”), these people Christ considered more guilty than Pilate, for they knew the Scriptures which contained prophecies about Christ (John 5:39), and on the other hand they knew enough of Christ’s work (John 15:24), which could not be said of the procurator who was far away from the questions stirring up hostile feelings towards Christ in the hearts of the Jews.

19:12. From that time Pilate was looking for an opportunity to release Him. But the Jews cried out and said: if you let him go, you are not Caesar’s friend. Anyone who makes himself a king is an opponent of Caesar.

“From that time”. Pilate liked what Christ said about him. He saw that the defendant understood his predicament and treated him leniently. It is in this sense that the expression ἐκ τουτου must be understood here.

“you are not Caesar’s friend.” Pilate especially persistently began to try to obtain the release of the defendant, although the evangelist does not report what his efforts were. This intention was noticed by the enemies of Christ, who in turn intensified their efforts to bring about the condemnation of Christ. They began to threaten Pilate with a report against his actions to Caesar himself (Tiberius), who, of course, would not forgive Pilate a frivolous attitude in a case concerning his imperial rights: for an insult to majesty he avenged himself in the most cruel manner , without paying attention to the height of the position occupied by the suspect in this crime (Suetonius, “The Life of the Twelve Caesars”, Tiberius, 58; Tacitus, “Annals”, III, 38).

19:13. When Pilate heard this word, he brought Jesus out and sat down on the judgment seat, in the place called Lithostroton *, which in Hebrew is Gavata.

“sat in judgment” (ἐκάθισεν). The threat of the Jews worked on Pilate, and he, having changed his mind, again brought Christ out of the praetorium and himself sat on the judgment seat (βῆμα). He had, of course, sat on it before, at the beginning of the judgment against Christ, but now the evangelist marks Pilate’s ascent to the judgment seat as something of special importance, and marks the day and hour of the event. By this the evangelist wants to say that Pilate decided to pass a judgment of condemnation on Christ.

Some interpreters translate the verb here standing ἐκάθισεν by the expression “set”, i.e. set (to sit) Jesus to make Him look like a real king sitting before his subjects. Although this rendering is grammatically admissible, it is hindered by the consideration that Pilate would hardly have dared to act so imprudently: he had just been accused of not sufficiently caring for the honor of Caesar, and if he now placed in the judge’s seat a criminal against Caesar’s commonwealth, would give the Jews occasion for still greater accusations.

“Lithostroton”. The place where Pilate’s judgment seat was placed was called in Greek Lithostroton (actually, a mosaic floor). This is what the Greek-speaking inhabitants of Jerusalem called it, and in Hebrew Gavata (according to one interpretation it means “elevation”, “elevated place”, and according to another – “dish”). In the Syriac translation of the Gospel of Matthew, the word Gavata is translated exactly with the Greek expression τρύβλιον – dish (Matt. 26:23).

19:14. It was then the Friday before Passover, about the sixth hour. And Pilate said to the Jews: here is your King!

“Friday before Passover” (παρασκευὴ τοῦ πάσχα). The evangelist John says that the condemnation of Christ for crucifixion and, accordingly, the crucifixion itself took place on the Friday before Passover (more precisely, “on the Friday of Passover”, thereby replacing the instruction of the evangelist Mark “on the Friday before the Sabbath” – Mark 15:42 ). In this way he wanted to mark the special significance of the day on which Christ was crucified. Christ is, so to speak, prepared for slaughter (the very word “Friday” in Greek means “preparation” and the readers of the Gospel well understood the meaning of this), as the lamb was prepared on the eve of the Passover for the night meal.

“about the sixth hour” (ὡσεὶ ἕκτη), i.e. at the twelfth hour. It would be more accurate to translate: about twelve (ὡσεὶ ἕκτη). Some interpreters (for example, Gladkov in the 3rd edition of his Interpretive Gospel, pp. 718-722) try to prove that the evangelist is counting here according to the Roman, and not according to the Judeo-Babylonian calculation, i.e. that he means the sixth hour in the morning, in accordance with the instruction of the evangelist Mark, according to which Christ was crucified in the “third”, that is, according to the Roman count, at the ninth hour in the morning (Mark 15:25). But against this assumption speaks the fact that none of the ancient church interpreters resorted to this method of harmonizing the testimonies of the evangelists Mark and John. Moreover, it is known that at the time when the apostle John wrote his Gospel, throughout the Greco-Roman world the hours of the day were counted in the same way as among the Jews – from sunrise to sunset (Pliny, “Natural History”, II, 188). It is probable that John in this case wanted to determine the time of Christ’s crucifixion more precisely than it is given in Mark.

In explaining the discrepancy between Mark and John, it must be taken into account that the ancients did not count time precisely, but only approximately. And it can hardly be assumed that John would have sealed exactly in his mind the hours of Christ’s sufferings that he was present at. Even less can this be expected from the apostle Peter, on whose words Mark wrote his Gospel.

In view of this, the approximate order of events of the last day of Christ’s life can be determined as follows:

(a) at midnight Christ is brought into the court of the high priest and subjected to a preliminary questioning, first by Annas and then by Caiaphas, with the latter also present some members of the Sanhedrin;

b) some time after that – two hours – Christ spends in a dungeon in the house of the high priest;

c) early in the morning – at the fifth hour – Christ was brought before the Sanhedrin, from where he was sent to Pilate;

d) after the end of the trial before Pilate and Herod and after a second trial before Pilate, Christ was handed over to carry out the sentence – crucifixion; According to Mark, this happened in the third hour according to the Jewish reckoning of time, and according to our time – in the ninth. But if we consider the later message of John, according to which Christ was crucified about the sixth hour, we must say that the third hour, or rather the first quarter of the day, was already over, and the sixth hour had passed and the second part of the day had already begun, in which (near its end, as appears from the words of John) the crucifixion of Christ took place (John 19:14, 16).

e) from the sixth (or, according to our reckoning of time, from the twelfth hour) to the ninth (according to us, to three o’clock in the afternoon) darkness came, and about three o’clock in the afternoon Christ breathed his last. The taking down and the burial were completed, of course, by sunset, for the night which began at sunset belonged to the coming Sabbath, when nothing could be done.

“here is your King.” Pilate makes a last attempt to save Christ, once again pointing out to the Jews that in the end they are handing over their king to be executed. “The other nations will hear – Pilate wants to say – that a king has been crucified in Judea, and this will serve as a shame for you.”

19:15. But they shouted: remove Him, remove Him, crucify Him! Pilate says to them: Shall I crucify your King? The high priests answered: we have no other king but Caesar.

The high priests are not willing to listen to Pilate’s exhortations: they have completely broken away from any national dreams of their own Jewish king, they have become, or at least appear to be, faithful subjects of Caesar.

19:16. And then he handed Him over to them to be crucified. And they took Jesus and led him away.

19:17. And bearing His cross, He went out to the place called Lobno, in Hebrew Golgotha;

19:18. there they crucified Him, and with Him two others, on one side and on the other, and in the middle – Jesus.

See the interpretation to Matt. 27:24-38.

Why does the evangelist John not mention Simon of Cyrene? It is very likely that he wanted to deprive the ancient Basilidian Gnostics of support for their opinion that Simon was crucified instead of Christ by mistake (Irenaeus of Lyons. “Against Heresies”, I, 24, 4).

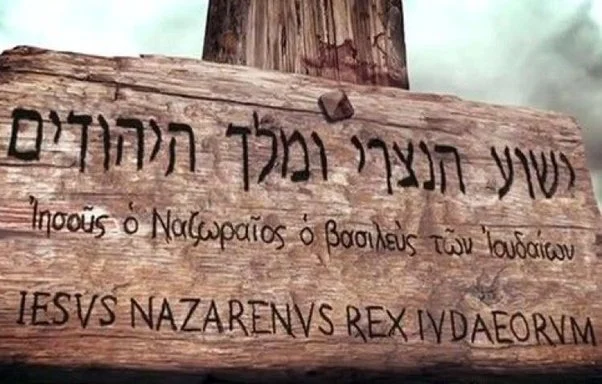

19:19. And Pilate also wrote an inscription and placed it on the cross. It was written: Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.

“wrote and inscription.” Evangelist John says about the inscription on the cross of Christ that the Jews were extremely dissatisfied with it, because it did not accurately reflect the crime of Jesus, but nevertheless it could be read by all the Jews who passed by Calvary, and many of them did not know how ” their king” has found himself on the cross.

19:20. This inscription was read by many of the Jews, because the place where Jesus was crucified was near the city, and the writing was in Hebrew, Greek and Latin.

19:21. And the chief priests of the Jews said to Pilate: do not write: King of the Jews, but that He said: I am the King of the Jews.

19:22. Pilate answered: what I wrote, I wrote.

“what I wrote, I wrote”. Pilate did not accede to the request of the Jewish high priests to correct the inscription, apparently wishing to embarrass them in front of those who had not participated in the handing over of Christ to Pilate. It is very possible that John, depicting this detail, wanted to indicate to his readers that God’s providence in this case was working through the stubborn pagan, announcing to the whole world the kingly dignity of the Crucified Christ and His victory (St. John Chrysostom).

19:23. The soldiers, having crucified Jesus, took His clothes (and divided them into four parts, one part for each soldier) and the tunic. The chiton was not sewn, but woven all over from top to bottom.

John does not give a detailed account of Christ’s stay on the cross, but he paints four striking pictures before the reader’s eyes. Here is the first picture – the parting of Christ’s garments by the soldiers, which is only briefly mentioned by the Synoptics. Only John reports that, first, the tunic was not divided into parts, second, the garments were divided among four soldiers, and third, that in the division of Christ’s garments the prophecy about the Messiah contained in Psalm 21 was fulfilled (Ps. 21 :19).

19:24. Then they said to one another: let us not tear him apart, but let us cast lots for him, whose shall it be; in order to fulfill what was said in the Scripture: “they divided My garments among themselves and for My clothing they cast lots”. So did the soldiers.

The soldiers assigned to crucify Christ were four, and therefore Christ’s outer garments were divided into four parts, but it is not known exactly how. The lower garment, the chiton, as a woven garment, could not be cut into pieces, because then the whole fabric would unravel. So the soldiers decided to cast lots for the chiton. It is possible that John, reporting this preservation of the integrity of Christ’s tunic, wanted to highlight the need for the unity of the Church of Christ (Saint Cyprian of Carthage. “On the unity of the Catholic Church”, 7).

Source in Russian: Explanatory Bible, or Commentaries on all the books of the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments: In 7 volumes / Ed. prof. A. P. Lopukhin. – Ed. 4th. – Moscow: Dar, 2009, 1232 pp.

(to be continued)