Fr. John Bourdin

After the remark that Christ did not leave the parable “of resisting evil with force,” I began to be persuaded that in Christianity there were no soldier-martyrs executed for refusing to kill or take up arms.

I think this myth arose with the advent of the imperial version of Christianity. It is said that the warrior martyrs were executed only because they refused to offer sacrifices to the deities.

Indeed, among them there were those who completely refused to fight and kill, as well as those who fought with pagans but refused to use weapons against Christians. It is not acceptable to focus attention on why such a persistent myth arises.

Fortunately, the acts of the martyrs have been preserved, in which the trials of the first Christians (including against soldiers) are described in sufficient detail.

Unfortunately, few of the Russian Orthodox know them, and even fewer study them.

In fact, the lives of the saints are full of examples of conscientious objection to military service. Let me recall a few.

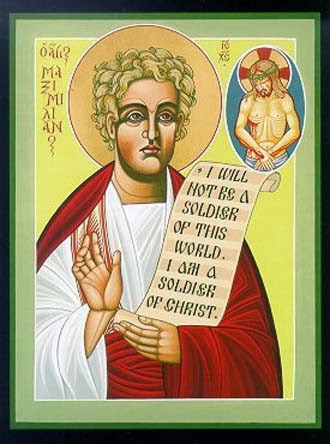

It was precisely because of his refusal to do military service that in 295 the holy warrior Maximilian was killed. The transcript of his trial is preserved in his Martyrology. In court he stated:

“I cannot fight for this world… I tell you, I am a Christian.”

In response, the proconsul pointed out that Christians served in the Roman army. Maximilian answers:

“That’s their job. I am also a Christian and I cannot serve.”

Likewise, St. Martin of Tours left the army after he was baptized. He is reported to have been summoned to Caesar for the presentation of a military award, but refused to accept it, saying:

“Until now I have served you as a soldier. Now let me serve Christ. Give the reward to others. They intend to fight, and I am a soldier of Christ and I am not allowed to fight.”

In a similar situation was the newly converted centurion St. Markel, who during a feast threw away his military honors with the words:

“I serve Jesus Christ, the eternal King. I will no longer serve your emperor, and I despise the worship of your gods of wood and stone, which are deaf and dumb idols.’

The materials from the trial against St. Markel have also been preserved. He is reported to have stated at this court that “… it is not fitting for a Christian who serves the Lord Christ to serve in the armies of the world.”

For refusing military service for Christian reasons, St. Kibi, St. Cadoc and St. Theagen were canonized. The latter suffered together with St. Jerome. He was an unusually brave and strong peasant who was drafted into the imperial army as a promising soldier. Jerome refused to serve, chased away those who came to recruit him, and together with eighteen other Christians, who also received a call to the army, hid in a cave. Imperial soldiers stormed the cave, but failed to capture the Christians by force. They take them out with cunning. They were indeed killed after refusing to offer sacrifices to idols, but this was rather the last point of their stubborn resistance to military service (a total of thirty-two Christian conscripts were executed that day).

The history of the legion in Thebes, which was under the command of St. Maurice, is more poorly documented. The acts of martyrdom against them are not preserved, as there was no trial. Only the oral tradition, recorded in the epistle of St. Bishop Eucherius, remains. Ten men of this legion are glorified by name. The rest are known by the general name of Agaun martyrs (not less than a thousand people). They have not completely refused to take up arms when fighting against heathen enemies. But they rebelled when they were ordered to put down a Christian rebellion.

They declared that they could not kill their Christian brothers under any circumstances and for any reason:

“We cannot stain our hands with the blood of innocent people (Christians). Are we an oath before God before we swear before you. You can’t have any confidence in our second oath if we break the other one, the first. You ordered us to kill Christians – look, we are the same.”

It was reported that the legion was thin and every tenth soldier was killed. After each new refusal, they killed every tenth again until they had slaughtered the entire legion.

St. John the Warrior did not completely retire from service, but in the army he was engaged in what in military parlance is called subversive activity – warning Christians about the next raid, facilitating escapes, visiting the brothers and sisters thrown into prison (however, according to his biography, we can assume that he did not have to shed blood: he was probably in the units guarding the city).

I think it would be an exaggeration to say that all early Christians were pacifists (if only because we don’t have enough historical material about the life of the Church from that time). During the first two centuries, however, their attitude to war, arms, and military service was so sharply negative that the ardent critic of Christianity, the philosopher Celsus, wrote: “If all men acted as you do, nothing would prevent the emperor from remaining completely alone and with troops deserted from him. The empire would fall into the hands of the most lawless barbarians.’

To which the Christian theologian Origen replies:

“Christians have been taught not to defend themselves against their enemies; and because they have kept the laws prescribing meekness and love to man, they have obtained from God what they could not have obtained if they had been allowed to wage war, though they might well have done so.’

We have to take into account one more point. That conscientious objectors did not become a major problem for the early Christians is largely explained not by their willingness to serve in the army, but by the fact that the emperors had no need to fill the regular army with conscripts.

Vasily Bolotov wrote about this: “The Roman legions were replenished with many volunteers who came to sign up.” Therefore, Christians could enter military service only in exceptional cases’.

The situation when Christians in the army became many, so that they already served in the imperial guard, occurred only at the end of the 3rd century.

It is not necessary that they entered the service after receiving Christian baptism. In most cases known to us, they became Christians while already being soldiers. And here indeed one such as Maximilian may find it impossible to continue in the service, and another will be compelled to remain in it, limiting the things he thinks he can do. For example, not to use weapons against brothers in Christ.

The limits of what is permissible for a soldier who has converted to Christianity were clearly described at the beginning of the 3rd century by St. Hippolytus of Rome in his canons (rules 10-15): “Regarding the magistrate and the soldier: never kill, even if you have received an order… A soldier on duty should not kill a man. If he is commanded, he must not carry out the command and must not take an oath. If he does not want it, let him be rejected. Let him who possesses the power of the sword, or is the magistrate of the city who wears the indigo, cease to exist or be rejected. Advertisers or believers who want to become soldiers must be rejected because they have despised God. A Christian should not become a soldier unless compelled by a sword-bearing chief. He must not burden himself with bloody sin. If, however, he has shed blood, he must not partake of the sacraments unless he is purified by penance, tears, and weeping. He must not act with cunning, but with the fear of God.”

Only with the passage of time did the Christian Church begin to change, to move away from the purity of the evangelical ideal, adapting to the demands of the world, which is alien to Christ.

And in the Christian monuments it is described how these changes take place. In particular, in the materials of the First Ecumenical (Nicaea) Council, we see how, with the adoption of Christianity as the state religion, those Christians who had previously retired from military service rushed into the army. Now they pay bribes to return (I remind you that military service was a prestigious job and well paid – apart from a good salary, the legionnaire was also entitled to an excellent pension).

At that time the Church still resented it. Rule 12 of the First Ecumenical Council calls such “apostates”: “Those who are called by grace to the profession of faith and have shown a first impulse of jealousy by taking off the military belts, but then, like a dog, have returned to their vomit , so that some even used money and gifts to be reinstated in the military rank: let them, after spending three years listening to the Scriptures in the portico, then ten years lie prostrate in the church, begging forgiveness”. Zonara, in his interpretation of this rule, adds that no one can remain in military service at all if he has not previously renounced the Christian faith.

A few decades later, however, St. Basil the Great hesitantly wrote about Christian soldiers returning from war: “Our fathers did not consider killing in battle to be murder, excusing, as it seems to me, the champions of chastity and piety. But perhaps it will be well to advise them, as having unclean hands, to abstain for three years from communion with the holy Mysteries.’

The Church is entering a period when it must balance between Christ and Caesar, trying to serve the One and not offend the other.

Thus arose the myth that the first Christians refrained from serving in the army only because they did not want to offer sacrifices to the gods.

And so we come to today’s myth that any soldier (not even a Christian) fighting for the “right cause” can be venerated as a martyr and saint.

Source: Author’s personal Facebook page, published on 23.08.2023.

https://www.facebook.com/people/%D0%98%D0%BE%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BD-%D0%91%D1%83%D1%80%D0%B4% D0%B8%D0%BD/pfbid02ngxCXRRBRTQPmpdjfefxcY1VKUAAfVevhpM9RUQbU7aJpWp46Esp2nvEXAcmzD7Gl/