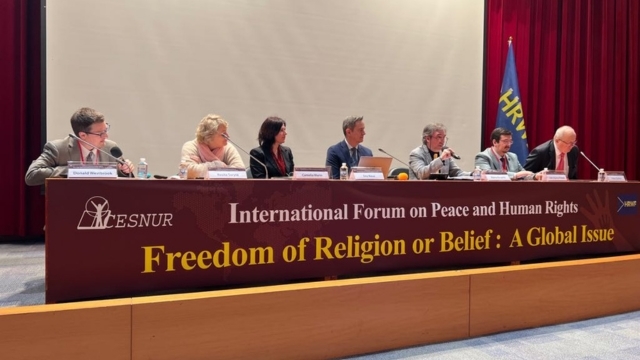

From April 5 to 11, Bitter Winter, its parent organization CESNUR, and the Brussels-based NGO Human Rights Without Frontiers organized a fact-finding tour of Taiwan, where they had decided to organize the 2023 edition of their International Forum on Freedom of Religion or Belief. The delegation included representatives from CESNUR and Bitter Winter (the undersigned and Marco Respinti, our magazine’s director-in-charge), Human Rights Without Frontiers (Willy Fautré, co-founder and director), the European Federation for Freedom of Belief (Rosita Šorytė), the European Interreligious Forum for Religious Freedom (Eric Roux), the Forum for Religious Freedom Europe (Peter Zoehrer), the Coordination des associations et des particuliers pour la liberté de conscience (Thierry Valle and Christine Mirre), Soteria International (Camelia Marin), the Fundación para la mejora de la vida, la cultura y la sociedad (Iván Arjona Pelado), the Italian Islamic association As-Salàm (Davide Suleyman Amore), and American scholar Donald Westbrook, from San José State University and the University of Texas at Austin.

The events they participated in were organized in cooperation and with the local support of the Taiwan Human Rights Think Tank, the New School for Democracy, and Citizen Congress Watch.

Taiwan was selected as the location for the Forum to express the scholars and human rights activists’ solidarity with the Republic of China at a time when it is the subject of geopolitical threats, and even leaders of Western democracies release ambiguous statements about its future. In these circumstances, as we said, we feel we are all Taiwanese.

The Forum, held on April 9 at National Taiwan University, and initiatives organized to discuss freedom of religion or belief issues at Aletheia University (which had already hosted a CESNUR conference in 2011) and Soochow University, and a seminar I taught at National Chengchi University, were international in scope. Echoing documents from the United Nations and the U.S. Department of State, we presented a global situation where problems of freedom of religion or belief are not getting better but worse.

The topics discussed ranged from the consequences of the war in Ukraine for religious liberty to media hostility to religion and religious minorities in several countries, the improper use of taxes to harass unpopular religious and spiritual movements, and specific problems in Eastern Europe, Russia, China, France, Belgium, Japan, Italy, and other countries. We noted, in particular, that groups stigmatized as “cults” (or “xie jiao,” in Mandarin) are among the most discriminated, slandered by the media, and persecuted. We also discussed, in dialogue with Taiwanese scholars, how different religious traditions such as Protestantism, Catholicism, Islam, Buddhism, and new religious movements approach the problems of freedom of religion or belief.

The purpose of the events was not purely academic. It was advocacy-oriented, as all the organizations represented struggle to improve the situation of freedom of religion or belief throughout the world. And it was also a fact-finding mission, as we wanted to learn about the situation of religious pluralism and religious liberty in Taiwan. We met with representatives and visited temples and churches of several religions and spiritual movements, including the Roman Catholic Church, some of the main Buddhist orders (including the headquarters of Fo Guang Shan), the Muslim community, the Church of Scientology, Weixin Shengjiao, and Tai Ji Men. We also had a very moving visit to the National Human Rights Museum, located in a former military compound where during the White Terror period opponents of the military regime where detained and tortured. We were privileged to have as a tour guide Fred Him-San Chin, a Taiwanese born in Malaysia who was wrongfully imprisoned for twelve years, from 1971 to 1983.

We visited human rights organizations and mainstream media, including the “Taipei Times” where we met with the daily’s editor (interestingly, on the very day when its main editorial quoted Bitter Winter), and the new TV network Mirror TV, and the Presidential Palace.

The two most important visits, however, occurred when we were received at the Legislative Yuan (Taiwan’s Parliament) by its President, Yu Shy-Kun, and visited the Control Yuan (a unique Taiwanese “fourth power” in addition to the legislative, executive, and judiciary, controlling the other three) and met with its President, Chen Chu, her collaborators, members of the Taiwan Human Rights Commission, and Pusin Tali, Taiwan’s Ambassador-at-large for international religious liberty. In both cases, we had exchanges lasting more than one hour on religious freedom issues. These visits were largely covered by the main Taiwanese media.

We reiterated to President Yu and President Chen that we love Taiwan, stand for Taiwan against international threats, and appreciate Taiwan’s effort to prove to the world that Chinese tradition and culture are fully compatible with democracy. On the other hand, we noted that no country is perfect, including our own countries in the West, and unsolved issues of human rights and freedom of religion or belief exist everywhere. If we noted some in Taiwan, it is precisely because we are Taiwan’s friends and care for its international image.

We discussed transitional justice, i.e., the effort to rectify human rights abuses after a transition from authoritarianism to democracy, a problem some of us coming from Eastern Europe or Italy, which also had to move from totalitarian regimes to democracies, are familiar with. We noted that Taiwanese laws offer measures to rectify abuses of human rights that happened before 1992, but that leaves open the question of violations of human rights after that date, including the politically motivated crackdown that hit several religious and spiritual minorities in 1996.

We told Taiwanese authorities that in most international conferences and events about freedom of religion or belief, including in the United States, while Taiwan is generally praised for its attitude towards religious pluralism, a particular case is invariably discussed, the one of Tai Ji Men. This menpai (similar to a school) of qigong, martial arts, and self-cultivation, whose Shifu (Grand Master), Dr. Hong Tao-Tze we also met, was one of the victims of the 1996 crackdown. It continued to be harassed through ill-founded tax bills even after courts of law, up to the Supreme Court in 2007, had declared that it was not guilty of any crime, including tax evasion.

We found that both President Yu and President Chen were well aware of the Tai Ji Men case, and knew that it is widely discussed internationally. While they emphasized the independence of Taiwan’s judiciary, they also assured us that they will operate to find a just, reasonable, and political solution of this long-lasting case. We told them that, as foreign scholars and human rights experts, it would be arrogant for us to tell Taiwanese how to solve a Taiwanese problems. But we put ourselves as their disposal, as friends both of Taiwan and of freedom of religion or belief, to help with suggestions if requested, and participate in a dialogue aimed at solving a case that creates problems for its international image Taiwan certainly does not need in this particular historical moment.

We felt at home in Taiwan, were moved by the warm welcome we received everywhere, and some of us even suggested that Taiwan will become the permanent home of our religious liberty Forums. We were also very much impressed by how many Taiwanese political and cultural leaders are familiar with Bitter Winter, and assured them that we will continue our efforts to provide every day quality information on issues of freedom of religion or belief.

Article first published in BITTERWINTER