Written by Kalin Yanakiev

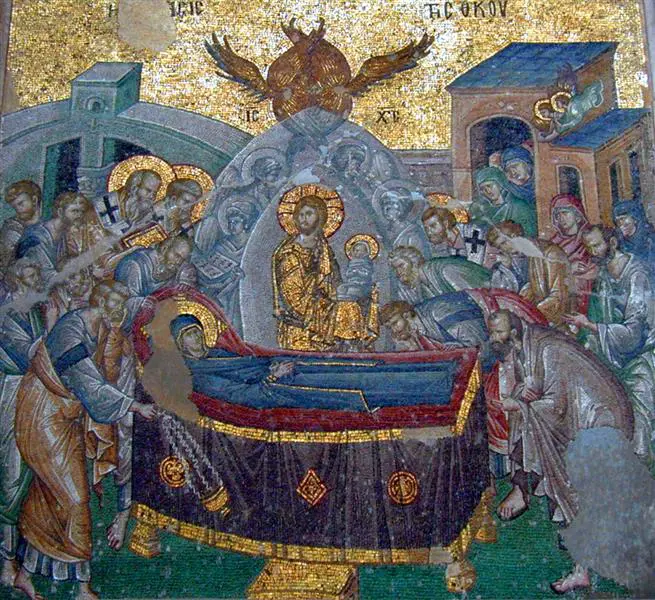

There is a unique paradox in the Orthodox iconography of the Mother of God – extremely difficult to articulate, though at the same time very clearly felt when we compare this face with Western-Renaissance images of the “Madonna”. The thing is, for all its deep and peaceful spirituality, the Immaculate Orthodox Icon can hardly be defined as “beautiful” or “lovely”, as “captivating” or “charming”. This is difficult, however, not because any deprivation is felt in the image, but because in the face of her incomparable and all-surpassing chastity, definitions of this kind sound somehow impious – too bold and, in any case, inadequate for the description of her character. The Virgin is chaste in a unique, unique way. She is – dare I say it – so chaste that she’s no longer… “beautiful”.

How could we explain this paradox – the holy non-beauty of the image of the Virgin in Orthodoxy, where “loveliness” turns out to be not exactly absent, but rather a transcended category?

To answer this question, let us first look at any icon of the Immaculate Conception and try to say how it most immediately differs from Renaissance images of Virgo Maria. Don’t we first of all have a feeling that the Orthodox icon painter – in contrast to the Western artist or sculptor – has somehow fundamentally and essentially devoted himself to giving this Most Holy and otherwise completely and “immaculately” female image, even the most sublimated, even the most -enlightened gender characteristics. Do we not have the feeling – however paradoxical this may sound – that he did not dare to give the Mother of God a glimpse of her naturally beautiful femininity? So look carefully at this unique flesh without carnality – flesh woven, as it were, only from the soul and mental silence, and compare it with the blossoming corporeality of some of the Western Virgins: somewhere – a little more rustic, healthy and pure, elsewhere – aristocratic-cool and solemn . Look at this peculiar femininity without femininity – washed as it were of its gender, though not sexless, and compare it with the fresh “veneracy” of too many Western Madonnas – somewhere spring-tender, elsewhere – maturely regal. Look, I say, at this strange beauty without charm—as if all chastity and humility—and compare it with the frank loveliness of almost all the Renaissance Madonnas—self-confident, self-conscious—somewhere a little narcissistic, elsewhere even coquettish. See, finally, this immaterial flame of the Spirit, which has literally burned away all sensuality, which shines from her face, making it in a peculiar way ageless, and compare it with the full-bloodedness of the Western Madonnas—somewhere young-faced maidens, elsewhere—mature Roman or German matrons. Carefully compare the two rows of images to see that although both of them undoubtedly show us virgins – still – the Orthodox Mother of God does not seem to be a Virgin in the same way that the Western one is. And as it were, indeed: the immediately striking difference here is precisely that the Western Virgo is definitely feminine, definitely lovely in its feminine purity. She is a Virgo, but a Virgo, if I may say so, in the essentially gendered sense of the word. She is the pure woman in her sex, and as such—though perfectly, aristocratically pure—remains in it, remains in her sex without transcending it, and therefore inspires in the beholder the feelings which the beautiful virgin woman naturally and primordially inspires. Not a word – these feelings, given the nature of the image, are extremely sublime. But they are, nevertheless, feelings inspired by the beautiful woman – by the woman of supreme beauty, ideal femininity, and therefore they are feelings of infatuation: of chivalrous and platonic adoration of the Virgin.

It is precisely this “beautiful femininity” of the Western Viigo Maria that is alien to the Orthodox Virgin’s face. It is foreign to him, although – we must note this once again, because it also contains the paradox – it is foreign to him not in the elementary negative sense of this word, but rather in a difficult to express (but clearly visible in the icon) exceeding the feminine “loveliness” sense.

For, on the other hand, it is not subject to any doubt that in the Orthodox Virgin’s face we do not perceive a trace of unnatural gender idiosyncrasy such as that which we can see, for example, in some ancient images of pagan goddess-virgins – figures with a masculine, hermaphrodite (and therefore unfeminine) appearance. In contrast, the Mother of God of the Orthodox icon is completely female – completely and flawlessly “female hypostasis”. However, it is she – this “feminine hypostasis” – that is, if I may say so, perfectly washed by the lovely femininity. Her image is contemplated, so to speak, comforted by the feelings – in super-sensual ecstasy, which is why it radiates not exactly inspiration for the imagination and emotions, but peace – a peace that leads out of them and introduces into the purely spiritual sphere of prayerfulness.

And so, in Orthodox iconography, the Mother of God is a Virgin in an exclusive sense of this word. I would even venture to say that in her icon she is neither simply a virgin woman, nor simply a noble mother-woman, but a woman, as it were, freed from the very limitation, passion, and naturalism of sex; freed, one might say, from the sexual guilt of the natural man—a woman virgin of sex. Completely female by nature and at the same time extremely non-gendered, hyper-gendered by grace. Completely oversexed, I say, because she is perfectly chaste – chaste to the point of overcoming the very half-ness of human nature, and completely female – because it is she, the woman Mary, who is here so perfectly spiritual and so exceedingly chaste.

Such a virgin woman (and yet a woman) is the Mother of God of the Orthodox icon, and this is determined by the exceptional personal holiness in which she is remembered in the ecclesiastical lore of the East. Let’s remember that Orthodoxy confesses the Virgin as the holy in a unique sense, i.e. not just as the holy, but as the pre-holy, the all-holy (in Greek: Παναγία): a woman, the only one who has reached the fullness of sanctification and in this respect yielding only to the Son of God born of her in the flesh, Who is holiness itself. The Mother of God of Orthodoxy is truly the “living temple of God” on earth, i.e. she is sanctified to the point of being a flesh-temple, a being-temple, in which therefore the light of the One to Whom the temple is already dawns, the light of the Godhead, not just the flesh that is this temple.

However, we also see something similar when we look at the way in which the motherhood of the Immaculate is depicted on Orthodox and Western Renaissance icons, motherhood, which, as we know, is inseparable from the virginity of the Mother of God.

Let’s compare the two rows of images once more.

Aren’t we forced to admit here, too, that although both the one and the other are “mothers” to us, the Orthodox Mother of God does not seem to be a mother in the same way that the Renaissance one is. So notice how symptomatically Renaissance art is attached to the representation of the Mother of God in its most immediate and most primal, even natural manifestations. In it, the Mother of God is very often shown to us here as a mother caressing the Infant, blissful and playing with Him, then as a mother intensely and deeply suffering for her Child, then even – as nursing Him from her breast, a nurse. It goes without saying that all this is very touching, charmingly intimate and sometimes manages to evoke an almost heart-wrenching tenderness, but… Are we not still left with the feeling that the earthly side of the mystery is too much revealed here, that it somehow even has enveloped and suffocated – him, the unattainable and unique, bright sacrament of carrying God Himself in the lap of a woman?

On the contrary: it is precisely this exciting sight of the soulful, womb-warm, reaching its luxuriant “entelechia” femininity of the mother that is especially muted in Orthodox icons. Looking at them, we will certainly feel how deeply and fundamentally impossible it is for the Orthodox icon painter to allow himself such a daring and presumptuous penetration into the mysterious intimacy of the Immaculate Mother with her divine Infant, with the Son of Man, Who is far from being simply “Marian” . All this is foreign to the Orthodox icon, although – and here we must repeat this again – there is not a trace of coldness or non-commitment in the face of the mother with the Child. Rather, we have before us an infinite delicacy, holy trembling and detachment of the mother in this visible, close to her and yet infinite mystery of the Infant in her lap.

Emphasizing once again this element that surpasses the flowering of motherhood in the Orthodox icon, I would say that in Western images we really see the image of a noble and devoted mother, but, with all our affection, we fail to achieve in it the face of the only one, of God mother, of the Virgin Mother, of the Immaculate Mother of God.

How are we to clarify this delicate, subtle, but very definite difference between the two sets of images? How do we articulate our deeply felt dissonance between that undeniably pure, captivating, and yet disturbing and ambiguous loveliness of the Western, Renaissance Madonnas, on the one hand, and that strangely hypersexual, unlovely, but undeniably all-surpassingly-holy chastity of the Orthodox faces of the Purified? How can we explain the fact that precisely in the immanent and definitely present feminine charm of the Western Madonnas we feel a, so to speak, lack of “virginity” and, on the contrary – that in the certain absence of charm, of femininity and, as it were, even of sexuality in the Orthodox faces of the Virgin, we feel the mysterious presence, the essence of the Most Holy?

I am sure that the Orthodox sense knows the answer to these questions very immediately and clearly, although the absence of a special theological reflection on the fundamental aesthetic categories applied to icon painting makes its formulation an infinitely delicate task. In fact, I think that the main thing is that in the ontology of the Orthodox icon “beauty” in the traditional sense of its application exists and must exist as an essentially overgrown, objectively irrelevant category. A category, I say, outgrown and irrelevant in principle, because it is constitutively incapable of manifesting the nature of the holy face.

“Beauty” – we must definitely say – as it is known to us in ancient and Renaissance-New European aesthetics, characterizes the image of the natural man – of man in his natural and (precisely because of that) gender-separated, gender-limited, ontologically half-guilty being. That is why “beauty” – as the ancients astutely noted this – is, as far as the characterization of man is concerned, in an essential way necessarily either male or female beauty, i.e. it is of necessity or wonderful “manliness” (in the terminology of the ancients – dignitas – “significance”, “impressiveness”, “importance”) or lovely “femininity” (venustas, i.e. “loveliness”, “gracefulness”, “loveliness”, “veneracy”). So it is in the natural feeling of the natural man, so it is in his aesthetic attitudes. And this is because in the realm of nature itself, man resides (and resides in his idea), in gender division, in half-ness—he is either “male” or “female,” and every idiosyncrasy, any gender indeterminacy or confusion in his particular face represents the imperfection of “masculinity” or “femininity” (which are – as perfections – the beautiful). As regards the female face in particular, to the “feminine hypostasis” of man, her beauty, that is, her perfect “femininity,” her venustas appears either as the charm of the clear and unblemished sex—as femininity in its pristine purity , or as “motherhood”, i.e. fulfillment of gender realized in its ideal expediency – as femininity in its fulfillment. So it is in the realm of naturalness, where the characteristic of “beauty” is relevant, applicable to the ontologically divided human being.

However, neither the beauty of the pure, unblemished gender (the beauty of virginity), nor the beauty of the gender that has reached its flowering (the beauty of motherhood), are capable of manifesting in the female face its holiness, and this is so for a very important reason. In the sanctity (both of the man and of the woman – it doesn’t matter) in the face of the depicted shines no longer just the nature, not just the idea of the woman or of the man, but rather in their nature, in their concrete hypostasis shines the light of the one who surpasses their being Holy Spirit. Therefore, in the holy face, the “flesh”, the “hypostasis” of the man or the woman do not shine by themselves, but with the light of the Spirit – they are oh-spirit-created faces, spirit-bearing faces. And, as is known, the Holy Spirit is neither “male” nor “female”, namely “holy”, i.e. supernaturally and Easternly “whole”, all-wise. That is why, therefore, as pierced by the Holy Spirit, as spirit-bearing, the human face – whether it is a man or a woman, it does not matter – no longer radiates its natural, created, sexual “beauty”, but what exceeds it, the supernatural for the human face chastity. He is holyly chaste, and that is different from “feminine” or “masculine”; different, therefore, from “beautiful” – dignified or venereal. In the sanctified human face – in so far as it has become spirit-bearing, oh-spirit-created, deified – one can no longer see its gender limitation, not its half-guilt (even in its perfection, in its “beauty”), but that which which transcends this limitation, which is transcendent of gender in general – of “femininity” or of “masculinity” – and which has no other name than holiness – irreducible to nothing else and inferable from nothing else holiness per se. This holiness ripens, of course, in him, in the man who has attained it – it ripens, therefore, in the man or in the woman, but still holiness ripens in them, and therefore ripens something more than their “masculinity ” or “femininity”, something more than the dignitas and venustas that characterize them, namely: the chastity that surpasses them, dwarfs them.

All of this ultimately shows us why in the Orthodox icon of the Mother of God (remembered specifically and above all as the All-Holy, Παναγία) we meet a face so special and so difficult to characterize: the face of a woman – completely a woman, who at the same time somehow it is not feminine, it is not sexually beautiful, and at the same time it is not so not because it is sexless or sexless, but because it is more than feminine, more than beautiful – it is washed out of sexuality, it is all-wise

Source: This text was first published in Portal Kultura (https://kultura.bg) on August 15, 2016 (in Bulgarian).