The Balkan Peninsula, as a crossroads between the Middle East and Europe, as well as a center of cultural interaction between the peoples of the East and the West, is the subject of serious attention from the Church of Christ. Shortly after the holding of the Apostolic Council, probably at the beginning of the second half of the year 51 AD. Paul begins his second missionary journey. We must note that the first Christian history, the Acts of the Holy Apostles, although it recreates the stages of geographical distribution of Christian communities from Eastern Asia to Rome, aims to reveal the inclusion of not only Jews, but also Gentiles to Christianity.

The sources for the preaching of the Apostle Paul are found in the Holy Scriptures themselves. During the second evangelistic journey of the apostle, the Spirit of God did not allow Christian preaching in the regions of Asia Minor, but brought the apostle to Troas together with Ap. Silas, Timothy and Luke. App. Luke tells how in Troas “a vision appeared to Paul at night: a man, a Macedonian, was standing before him, begging him and saying: “Go to Macedonia and help us!” After this vision, we immediately asked to leave for Macedonia, because we understood , that the Lord has called us to preach the Gospel there. And since we were traveling from Troas, we came directly to Samothrace, and the next day to Naples, and from there to Philippi, which in that part of Macedonia is the first city – a Roman colony” (Acts 16:9-12).

Reaching Philippi is no coincidence through the island of Samothraki. The preaching of Christ’s faith in Europe began here – the thousand-year-old Balkan Thracian place of worship. It is interesting why preaching was not allowed in the Asia Minor provinces. It is suggested that St. Paul is most likely responding to the invitation of the Macedonians from Philippi, who later play a defining role in his environment, but on the other hand, how can these Philippians (Macedonians) end up with him when we know that his companions were of Asia Minor origin? From this we judge that App. Pavel, who knows Greek, takes with him people from the local Eurasian population. He used their linguistic knowledge among non-Greek speakers. The mission of Ap. Pavel is “organized according to the model of capillary penetration”. The apostle did not seek to cover a large space as a territory, but rather to build strongholds that would become bases of departure for subsequent preaching. For this purpose, he skillfully and successfully used both the infrastructure of the empire and the network of the ancient city (polis) with its specific cores. It goes around the important centers and cities at the crossroads, which are a kind of gathering places for the inhabitants of the district. People often go there because they are the seat of the administration and the courts. In practice, the word reached more people than it would have if the apostle had traveled from place to place. This has also been noted by the analysts of his missionary route.

St. Paul firstly headed for the famous Via Egnatia, making a detour to Athens and Corinth. General observations, however, show that a group of his disciples managed to connect the so-called “Central” (diagonal) road leading from Rome to Byzantium and passing through Vindobona (present-day Vienna), Sirmium (present-day Sremska Mitrovica), Naisos ( present-day Nis), Serdika (present-day Sofia), Philipopol (present-day Plovdiv), Adrianople (Adrien), Byzantium, which will be discussed below. Other apostles were appointed to instruct the newly converted believers: the evangelist Luke in Philippi, Silas and Timothy in Berea. Later in his Epistle to the Romans ap. Paul explicitly confirms the fulfillment of his task by saying that he “delivered the teaching of Christ as far as Illyricum” (Rom. 15:19). In his notes on the Epistle of the Apostle Paul to the Romans, bl. Theophylact Bulgarian writes: “the apostle Paul says: “because I spread the gospel from Jerusalem and the surrounding area even to Illyricum”. Do you want proof of what I am talking about, says (App. Paul)? Look at the large number of my students – from Jerusalem to Illyricum, which coincides with the borders of today’s Bulgaria. He did not say: I have preached, but fulfilled the gospel, to show that his word was not fruitless, but effective. Lest you think that he walked on a straight and broad road. “And the surrounding area,” he says, i.e. I have gone through the nations, preaching both to the north and to the south…”

St. app. Luke speaks of Philippi as “the first city in this part of Macedonia” (πρώτη της μερίδος Μακεδονίας πόλις, κολωνία) (Acts 16:12). Some think that the apostle errs in using the word μερίς (part), and justify their contention by saying that it never signified a periphery, a province, or any geographical division. It is assumed that some error was originally present in the text, and someone, wishing to correct it, replaced it with the word “μερίς”.

However, archaeological finds from Fayum (Egypt) show that the colonists there, many of whom came from Macedonia, used the word “μερίς” to distinguish the regions of the province. In this way, it is established that “Luke had a good idea of the geographical terminology used in Macedonia”. Archeology “corrects” the pessimists and proves St. Luke right. The Philippian women, who were the first to be enlightened by the apostolic preaching, were proselytes – Macedonians and Phrygians, and they prayed to the Jewish God, identifying him with the ancient Thracian-Phrygian deity “Vedyu” – “Βέδυ”. To this deity, the Macedonians owe, according to legend, the salvation of their dynasty[9]. Archaeologists have confirmed with accuracy the topographical information described in Acts. According to Prof. Thompson, from the result of their excavations, carried out from 1914 to 1938, we have obtained “accurate information about the place where the Gospel was first preached in Europe”.

After Philippi ap. Paul continued through the cities of Amphipolis (near the village of Neochori), Apollonia (on the way between Amphipolis and Thessaloniki), Thessaloniki, Veria, establishing church communities everywhere. His disciples spread his work in Macedonia, Illyria, and Thrace despite opposition from interested Gentiles and Jews (see Acts 16:9-12 and Acts 16 and 17 in general). According to ancient church tradition, St. Ap. Paul also preached in Thrace. More specifically, the hypothesis that Nicopolis, which is mentioned in (Titus 3:12), is identical with Nicopolis ad Nestum, located on the banks of the river Mesta, is also proposed. Some researchers mark the city on geographical maps showing the path of ap. Paul. Archaeological excavations and diocesan lists reveal that it was a well-known episcopal center as early as the 4th-5th centuries. Thus, by God’s suggestion, the ethno-cultural region of Thrace-Macedonia is indissolubly present in the history of Christianity from the 1st century. Paul’s assessment of this region is a model of blameless faith and participation in the grace of Christ. According to St. Ap. Paul, who felt called to preserve Christ’s teaching without impurities, the churches here were a model for the entire Christianizing world at that time.

About the sermon of St. Ap. Andrei has an extensive historical and literary book. On the one hand, there is the rich apocryphal literature, and on the other, there are the short catalogs of the apostolic missionary journeys. But the most essential problem is how to differentiate historical fragments from apocryphal legendary layers and correctly interpret the extremely mysterious geography of Scythia and ethnonym nomenclature (Scythians, Myrmidons, Anthropophagi, etc.)? Another question raised by scholarship is: do the legends about St. Andrew have a political aspect to the rise to the throne of Constantinople? One of the possible answers is that the Church of Constantinople supposedly does not feel particularly confident in its status, determined at the Second Ecumenical Council in 381 and confirmed by rule 28 of the IV Ecumenical Council in 451. Hence the tendency to compensate for the absence of reliable historical tradition through ad hoc legends and apocrypha. This is how the establishment of the Constantinople Cathedral of the brother of the ap. Peter – app. Andrei Parvozvani, also called “Parvozvanna”. However, this is not true, because there are various legends about almost all the apostles. The Eparchy of Constantinople derives its authority not simply from its founder from the number of apostles, but from its early Christian history, with which it can already compete with the claims of primacy of the Roman Curia. These statements may logically lead to such an opinion, but the 28th rule of the IV Ecumenical Council, with its interpretation by the canonists, introduces us to another angle of the problem. The explanations given by Ep. Nicodemus (Milash) gives us a clear idea that in the 6th century the Roman Church accepted the decisions of the 4th Ecumenical Council and until then there was no need to assert any apostolic authority. Moreover, the popes until the 9th century did not claim any absolute, universal, infallible, divine authority of their see. The Church, led by the Holy Spirit, foresaw that it was possible for Rome to deviate from the purity of the faith, and therefore established that the Constantinople Cathedral should be the first after it, equal in honor and second in administrative magnitude. Following the development of the criticism of the sources for the apostle Andrew, one cannot fail to notice that it makes a circle and, after a period of extreme skepticism, again approaches the traditional conclusions. These conclusions are that the activity of St. Ap. Andrei developed precisely on the Balkan Peninsula. Church tradition about St. Andrew was recorded by the early Christian writer Eusebius of Caesarea. He informs us that “to Thomas, as the legend narrates, Parthia fell by lot, to Andrew – Scythia…”. Similar information was also recorded by authors or sources such as Tertullian, Epiphanius, Synaxar of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, Menology of Basil II. From the analysis of the text, recorded by Eusebius and going back to Origen, we can date this tradition to the end of the II – beginning. of the 3rd century. The witnesses of the sermon of the ap. Andrew in Thrace and Scythia are a whole host. Eusebius also repeats Rufinus (“as it has been handed down to us”) and Eucherius of Lyons († 449) (“as history tells”). To them we will add Isidore of Ispalia, who also affirms that the apostle Andrew received a share to preach in Scythia and Achaia. The notice of St. Hippolytus of Rome, who was a student of St. Irenaeus of Lyons, is also authoritative. In his short treatise on the twelve apostles, he writes: “Apostle Andrew afterwards, having preached to the Scythians and Thracians, suffered death on the cross in Patras of Achaea, where he was crucified on an olive tree and buried there.” Dorotheus spoke even more fully about this preaching of Andrew: “Andrew, brother of the apostle Peter, went around all Byzantium, all Thrace and Scythia and preached the Gospel.” Even with a possible interpolation of the authorship of St. Hippolytus or Dorotheus, we have no reason to doubt the veracity of the information presented. Indirect confirmation of St. Andrew’s apostolic preaching is also found in St. John Chrysostom, who delivers a special eulogy for the apostles, where he says the following: “Andrew enlightens the wise men of Hellas.” Here “Hellada” is not some toponymic fiction, but a real people, similar to all the others mentioned by the Saint of Constantinople, delineating the geographical regions of the apostolic preaching. It is unreasonable to believe that app. Andrew preached in Scythia, but not in Thrace. Finally, again, the entire church tradition tells us that the activity of Ap. Andrei is developing in the Eastern part of the Balkan Peninsula. In Dobrudja, on the border between present-day Bulgaria and Romania, there are the following toponyms – “St. Andrew’s stream” and the “cave of St. Andrey”, where today the monastery “St. Andrei” “about whom legends related to st. Andrey and his three students Ina, Pina and Rima”. Some folk songs in Dobruja and on the left side of the Prut River remind of a missionary mission of St. Andrew in these lands. The power of the tradition about the preaching of the Apostle Andrew is so prevalent in the peoples who inhabited the so-called Scythia that even the Bulgarians of Altsek in Italy in the 7th century wore Andrew’s cross in a Hyksos shape. And it spread throughout Medieval Christian Europe, so that in the 14th century in Scotland, the nobles who considered themselves Scythian heirs could ask the Pope for ecclesiastical independence from England, citing Andrew’s sermon among the Scythians as an argument. Information has also been found about another apostle who preached in the Balkans – St. Ap. Philip. He is one “among the 7 deacons who baptized Simeon and the eunuch, was the bishop of Scythian Thrace”.

General written sources for the spread of Christianity

There is basic source data for the associates of the app. Paul and Andrew, who continue their work. Their number is exceeded only by the apostles from Asia Minor and the Middle East[28]. More than 20 apostles preached Christianity on the Balkan peninsula, and those who suffered for the faith numbered hundreds, even thousands. At the head of the Christian communities in Serdica, Philippopolis, Sirmium and in Tomi (Constanza) as early as the middle of the first century, there were bishops from the narrowest circle of Christ’s disciples, whom the Church marks as the “seventy apostles”. It is no coincidence that one of the ancient biographies claims that St. Cornelius was from Thrace, Italy. We have reason to see the presence of the Balkan inhabitants first in the act of transmission of the new faith from the Jews who preserved the true worship of God to the Gentiles, among whom were the Balkan inhabitants. Their contact with the God-protected people of Israel has been documented since the period of the campaigns of Alexander the Great, and this has also been proven archeologically. Many Macedonians at that time inhabited Samaria, and Hellenes the coastal cities such as Gaza, Ascalon, Caesarea, Ptolemais, etc. The road from the Adriatic to the Danube, from where eastern traders moved to Italy and Pannonia, had a certain share in the early penetration of Christianity. So that the lands of the Balkan Peninsula are not only a place for spreading, but also a way for Christianity to penetrate into Europe. The reception, lively preaching and development of the Christian life of the principles bequeathed by the apostles themselves in these churches did not stop in the following years. Tertullian says that the succession in the churches founded by the apostle Paul was preserved until his time.

Let’s also look at the general reports about the spread of Christianity in the Balkans in the period I – V centuries. The chronology ranges from the II – III centuries, and the majority of the existing information is from the period IV – V centuries. The early reports are with panegyric in nature, they do not seek to fix the spread of Christianity in the Balkan region, but highlight its triumphal march throughout the Ecumenium. The earliest message of this kind is the testimony of the famous Christian ideologue Quinta Florenta Septimius Tertullian. He testifies that in the 2nd century. Christianity had already penetrated among the Getae, Dacian, Sarmatian and Scythian tribes. This is what the text says: “Et Galliarum diversae nations et Britanorum inaccesa Romanis loca, Christo vero subdita, et Sarmaturum et Dacorum et Germanorum et Scytharum et abditarum multarum gentium et provinciarum et insularum nobis ignotarum et quae enumerare minus possemus”. There are opinions that Tertullian is an apologist and for this reason, he uses a lot of exaggerations and hyperboles. As an argument in support of this distrust, they consider a passage from a commentary on Origen’s book as an interpretation of the Gospel of St. Ap. Matthew. He believes that the Gospel has not yet been preached in the lands around the Danube. By the way, Origen’s work is also apologetic, as shown by the fact that the Alexandrian author wishes to answer the pagan Porphyry, who denies the truth of the words of the Savior (Matt. 24:14). The pagan philosopher believed that evangelism was complete and the world should no longer exist. Elsewhere, Origen writes that Christianity attracted a large number of followers among “every nation and race of men,” which means that it also spread among the barbarian world. Another writer who confirms that Christianity existed around the Danube River is Arnobius, who claims that there were Christians among the Alemanni, the Persians and the Scythians[32]. The next moment in the process of Christianization was the Gothic invasions of the 3rd century. There is indirect confirmation from the pages of the “Carmen’s Apologetics” by the poet Commodianus. He informs that the Goths took many captives, among them Christians, who also preached among the barbarians living around the Danube. The same is confirmed by the church historian Sozomen, who mentions that the Goths living around the Danube took many captives from Thrace and Asia, among them many Christians. These Christians healed many sick people and many Goths accepted their faith. The statement of Socrates [34] that some part of the Sarmatians, after the defeat they suffered by the troops of the imp. Constantine in 322 became Christians, it is also confirmed by Jerome, who describes the triumph of Christ over the demons in his letter to Laetus: “From India, from Persia and from Ethiopia we every hour welcomed crowds of monks, the Armenians laid aside their quivers, the Huns learn the psalter, and warm the Scythian cold with the warmth of their faith – the golden and blond Geth army is surrounded by church tents. Perhaps that is why they fight against us with a bravery equal to ours, because they profess the same faith”. Ergo, Christianity was already spread in the lands south of the Danube, so that it could successfully seek its followers in the areas north of the river. The father of Church history, Eusebius, rarely mentions Balkan Christianity, but we know that he was a selective writer. As Prof. Helzer also says, knowing about the work of Africanus, Eusebius did not use his information because it was already known to the public, but looked for other sources. He mentions bishops of Anchialo and Debelt. Aelius Julius Publius is known to have signed the epistle of Serapion of Antioch to Cyric and Ponticus, in which he also gave the following testimony about Sotas, the bishop of Anchia: “Aelius Publius Julius, bishop of the colony of Debeltus in Thrace, I call God to witness that the blessed Sotas, bishop of Anchia, wanted to cast out the wicked spirit of Priscilla, but the hypocrites did not allow him”. Another Christian historian confirms that Christianity penetrated deeply into the Balkan Roman provinces: “the Hellenes, the Macedonians and the Illyrians… professed their faith freely because Constantine ruled there.” At the First Ecumenical Council in Nicaea, many bishops from the Thracian and Illyrian lands took part, and this is mentioned by all church historians, such as Eusebius, Socrates and Sozomen. Testimonies were also recorded by St. Athanasius of Alexandria (c. 300-373). We know that as a participant in the Council of Serdika in 343, he came to the Balkans. He indicates the peoples who accepted the “word of Christ” – the Scythians, the Ethiopians, the Persians, the Armenians, the Goths.

St. John Chrysostom delivered a sermon in a Gothic church, using as a metaphor, different animals – leopards, lions and lambs, to which peoples accepting Christianity are likened. The secularist point of view of some authors leads to an overexposure of the importance of the empire for the spread of the faith, namely, the sermon of St. John reveals to us that it was actually the work of the apostles and their assistants. The church is first of all a divine organism, and secondarily it also has its administrative institutions.

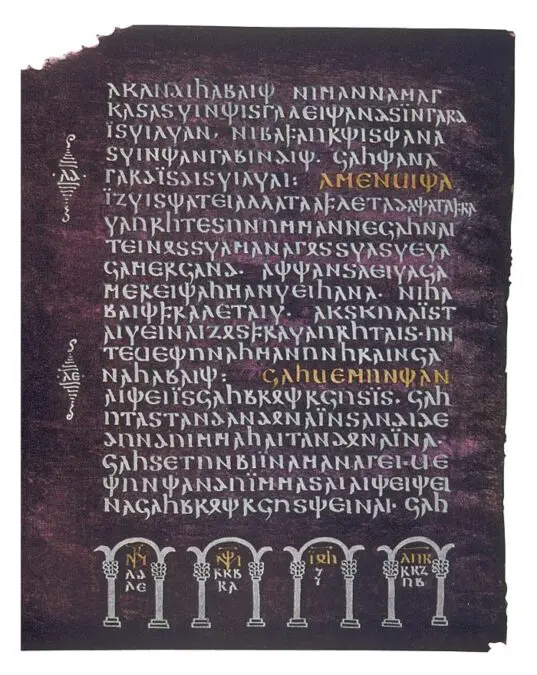

Photo: A page from Ulfila’s Silver Bible from the 5th century, “priest” is translated with the word god / Public Domain