Bioarchaeologists have re-examined the Paleo diet of people whose remains were discovered at early Neolithic sites in Greece, and found that their diet consisted mainly of plant foods, the proportion of which ranged from 58.7 to 70.1 percent. This is noticeably lower than that of people from the older Anatolian site of Neval-Chori, where animal products accounted for only about ten percent of the diet. Scientists noted that the economy of the Neolithic population of Greece was flexible: the gradual growth of animal husbandry was accompanied by the preservation of hunting. This is reported in an article published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

The process of transition from an appropriating to a productive economy (the Neolithic Revolution) is one of the turning points in the history of mankind. The domestication of cereal crops began no later than the 10th millennium BC in several centers of the Fertile Crescent, from where this type of farming spread to the rest of the Middle East and Europe. Soon there, people began the process of domestication of the Asian mouflon (Ovis gmelini), the bezoar goat (Capra aegagrus) and the primitive tur (Bos primigenius). Agriculture was brought to Europe by immigrants from Anatolia, who displaced most of the local population. Thus, the neolithization of Greece began around 6800 BC, and about 5000 years ago this process was completed on almost the entire continent.

Gisela Grupe, together with colleagues from the University of Munich, re-examined the results of the analysis of stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen in bone collagen, which were obtained during the study of the remains of Neolithic adults. These data refer to five early Neolithic Greek sites: Mavropigi (6600-6000 BC), Theopetra (6500-4000 BC), Xirolimni (6100 BC), Alepotripa (6000-3200 BC) and Franhti (6000-3000 BC). Paleobotanical and paleozoological studies of these sites suggested that the diet of the local inhabitants was based on C3 plants. An additional source of food was the meat of domestic animals, less often – wild ones. In addition, at the last two sites, the diet also included marine molluscs and fish. For comparison, scientists drew on data from the Anatolian site of Nevaly-Chori, one of the oldest settlements of the pre-ceramic Neolithic (about 8420–7470 BC).

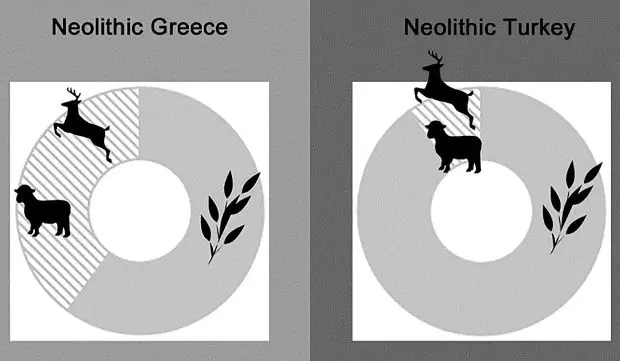

Bioarchaeologists reported that the inhabitants of Nevala-Chori mainly obtained protein through the consumption of C3 plants (87 percent). Other protein sources were wild (gazelles: 0–9.5 percent, red deer: 1.5–3 percent) and domesticated (0–11.1 percent). On average, the diet of these people consisted of ten percent meat food. Only five people, judging by the values of nitrogen isotopes, consumed more animal protein. The people from the sites of Mavropegy and Theopetra lived on fairly similar diets, which, according to scientists, is not surprising due to the location of these monuments and the time of existence. Thus, the inhabitants of Mavropegy mainly consumed C3 plants (69.4 percent), meat of roe deer (14.6 percent), sheep and goats (8.4 percent) and cattle (7.5 percent). People from Theopetra consumed slightly less C3 plants (61.1 percent), but more meat food, mainly due to an increase in the proportion of domesticated animals (31.6 percent). Scientists failed to build a model for the Xirolimni monument.

The study of coastal monuments has led to different results. Thus, people from Alepotripa also ate mainly C3 plants (58.7 percent), meat of domesticated animals (29.2 percent) and deer (12 percent). Although fish and seafood may have been included in the diet, the contribution from this food source was low, ranging from 0 to 2.5 percent. On the other hand, the consumption of sea fish (tuna) was clearly visible at the Franhti monument (6 percent). However, even there, the main source of food was plants (70.1 percent), as well as sheep and goat meat (11.9 percent) and deer (12.2 percent).

Bioarchaeologists concluded that in all studied populations, the daily diet consisted mainly of C3 plants – wild and domesticated cereals. Only one individual from Anatolia consumed a significant amount of C4 plants and, apparently, was a migrant. Evidence from the oldest monuments shows that early Neolithic populations lived on a largely vegetarian diet. The subsistence economy of these people changed gradually due to the increase in the contribution of meat food, and game meat was gradually replaced by products of domestic animal husbandry. Scholars have emphasized that an important aspect of the economy of the early Neolithic communities was flexibility. So, people did not completely abandon hunting, which guaranteed the supply of meat even at times when domestic animals died, for example, during epidemics.

Photo: Sidney Sebald et al. / Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2022