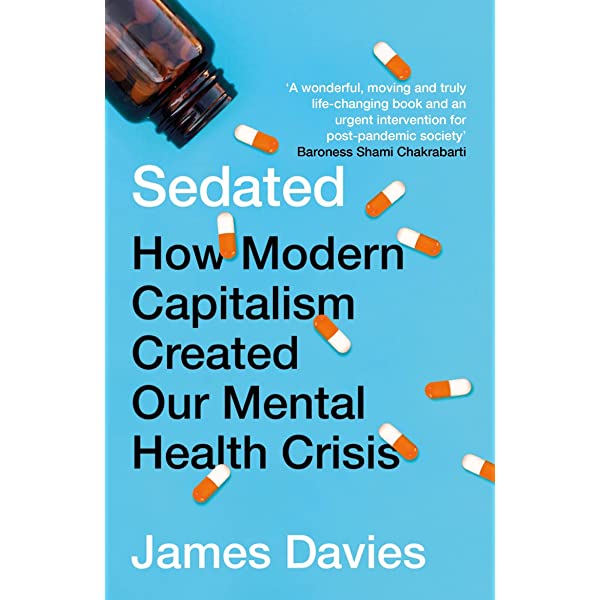

How Modern Capitalism Created our Mental Health Crisis. A provocative and shocking look at how western society is misunderstanding and mistreating mental illness. Perfect for fans of Empire of Pain and Dope Sick. In Britain alone, more than 20% of the adult population take a psychiatric drug in any one year.

Last April 9th, 2022, Irene Hernandez Velasco a reporter for Spanish newspaper El Mundo, published an astonishing interview with Dr. James Davies, author of “Cracked: Why Psychiatry is Doing More Harm Than Good“. For those who don’t speak Spanish, we offer here a translation, but its original can be found in the this link.

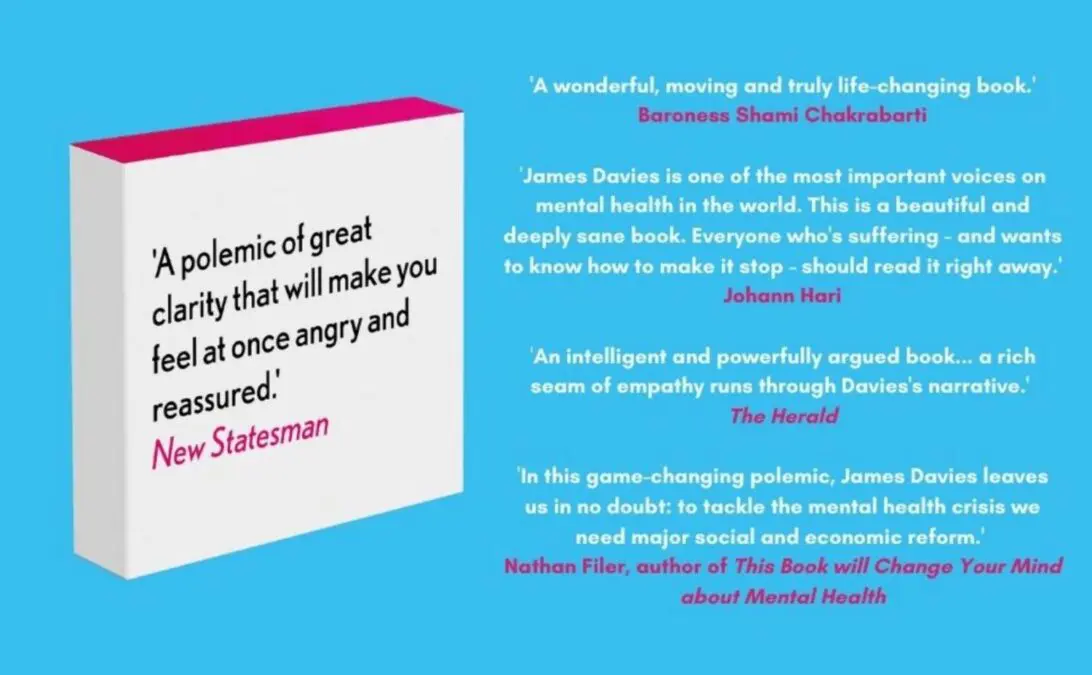

James Davies, Professor of Anthropology and Psychotherapy at the University of Roehampton (UK). In “Sedated: How Modern Capitalism Created our Mental Health Crisis” he reveals what is wrong so that, despite the enormous increase in the consumption of psychotropic drugs, mental illnesses do not stop rising.

Psychiatric prescriptions have increased in the UK by 500% since 1980, with all Western countries registering a huge rise. However, mental health problems have not only not diminished but have grown. How is it possible?

I think fundamentally it is because we have taken the wrong approach, an approach that medicalizes and over-medicates understandable human reactions to the difficult circumstances we often face.

Is it a coincidence that this increase in the consumption of psychiatric drugs began in the 1980s?

No, it is not by chance. Since the 1980s the mental health sector has evolved to serve the interests of today’s capitalism, neoliberalism, at the expense of people in need. And that explains why mental health outcomes haven’t improved over that time period: because it’s not about helping individuals, it’s about helping the economy.

Can you give us an example of that link between psychiatry and neoliberalism to which you allude?

From the point of view of neoliberalism, the current over-medicalization approach works for several reasons: first, because it depoliticizes suffering, it conceptualizes suffering in a way that shields economics from criticism. We see an example in the dissatisfaction of many workers. But that dissatisfaction, instead of giving rise to a debate about the poor conditions of modern working life, is addressed as something that is wrong within the worker, something that needs to be confronted and changed. And I could give you many other examples.

Is it then about turning a social problem into an individual problem?

Yes. It is about reducing suffering to an internal dysfunction, to something that is wrong within us, instead of seeing it as a reaction of our organism before the bad things that are happening in the world and that need our attention and care.

The data show that people with the worst economic conditions, those most affected by unemployment and poverty, are the ones who are prescribed the most psychoactive drugs. Does that also have something to do with the economy?

-Absolutely. Just look at what has happened during the pandemic. Single mothers living in large city blocks were three times more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety than people with a house in the country with a large garden. The circumstances one finds oneself in determine one’s state of mind. But instead of focusing on those circumstances through political reforms, what we do is medicalize the problem and think that we can treat it in clinics and health centers. That has been the main problem for the last 40 years, the arrogant idea that through a pill we can solve problems that are not rooted in neurochemistry, but in the world. And, ultimately, it is political reforms that we have to think about if we want to solve that problem.

And do you think that approach to psychiatry in line with neoliberalism is deliberate?

Well, there have been powerful industrial interests that have supported the over-medicalization of everyday life. That has been very good for the pharmaceutical industry, because the more people that can be classified as mentally ill or mentally disturbed, the bigger the market for products that seem to solve the problem. The pharmaceutical industry has absolutely promoted that idea in a very calculated way for the last 30 years. On the other hand, when it comes to governments I don’t think they have necessarily been colluding with the pharmaceutical industry. I think that it has rather had to do with ideologies and ideas that seem to fit with their own, and in this way they have privileged ways of intervening and thinking about stress and anguish that fit with their criteria. In that sense, the depoliticizing narrative is good from a political point of view. This mutual alliance between the pharmaceutical industry and political powers has been evolving slowly for 40 years and is what has led us to the situation in which we now find ourselves. I don’t think that alliance was necessarily calculated, it was simply the inevitable result of both finding some kind of support in each other.

Isn’t neoliberalism then just an economic paradigm?

No. We know from social history that the dominant economic paradigm at a time shapes social institutions, molds them to fit that system. So all social institutions, to one degree or another, change to serve that larger superstructure. We have seen it in schools, in universities, in hospitals… Why shouldn’t it also happen in the field of mental health? Of course it happens.

In the end, is psychiatry doing more harm than good?

I believe that if psychiatry does not recognize to what extent it is an accomplice of a system that harms, it is itself harming. Psychiatry can evolve, see to what extent it is complicit and can change. Psychiatry is a social institution that by nature is not harmful, it all depends on how it operates as a social institution. And at this time as a social institution, and given what it privileges, I would say that in many cases it is doing more harm than good. The data I provide in my book on the long-term prescription of psychoactive drugs I think illustrates this very well. These data show that these drugs are not only not generating the results that we would expect from an effective service, but that they are also harming many people who are negatively affected by these long-term treatments. And third, those drugs are costing an enormous amount of money. Putting all this together, I believe that psychiatry as a social institution is not acting as it should at this time.

He says that psychiatry is hyper-medicating many patients… But I guess there are people who really need medication, right?

Yes I agree. I am not anti-drugs or anti-psychiatry. Psychiatry plays a role in society, psychiatric medication plays a role for seriously distressed people. In fact, research shows that prescribing short-term psychotropic medications can be very helpful and advantageous. What I criticize is the overextension of a system that is now approaching a quarter of our adult population being prescribed some one type of psychiatric medication a year. That system is completely out of control. It is this excess that I criticize, the medicalization of problems that are actually social and psychological and therefore should be addressed with social and psychological interventions. Yes, there is a role for psychiatry in society, but not the one it currently represents.

When you talk about psychological interventions, do you mean doing therapy?

I think there are different ways to proceed. I think therapy plays a role, but I think we also need to recognize that therapy in the past has been responsible for reducing problems to internal dysfunction, family dynamics, or past incidents. We must understand that families are inserted into larger social systems. Suffering cannot be reduced to the family, because the family is often an expression of something else. A father who comes home in a foul mood may do so because he is depressed with his job, because he is in danger of his job, or because his salary is not enough. Those are factors that can make family life very difficult, and if therapists aren’t aware of that, it’s a big problem. I believe that therapy that takes political and social issues into consideration can be very supportive in raising awareness not only of immediate issues, but also of broader structures and how these affect health. That kind of therapy is very valuable. There are many psychological interventions that can be very helpful, but I don’t think we should stop there.

What else should be done?

I think we should also recognize that there are very serious and real social determinants of distress, and the only way to address them is through social policies. We need to think more about what kind of policies should be put in place to solve the current crisis we find ourselves in. Political reforms must be the central pillar of any mental health reform.

And do you think it will be done?

If history is any guide, we know that economic paradigms rise and fall. We have seen this over the last 200 years, and I suspect that many people are thinking that neoliberalism as an economic paradigm is coming to an end. As for what comes after neoliberalism, I hope it will be something with a more humanistic style, a kind of mixed economy capitalism. I believe that this could fit in with a vision of mental health that privileges political, social and psychological interventions over psychotropic drugs, knowing of course that there is a space for psychotropic drugs, but less than the one they occupy now. It is very difficult to know for sure where we are going to be, but I believe that there will be no mental health reform until there are political and economic reforms.

How have psychiatrists reacted to your book?

So far the reaction has been pretty good. I have friends who are psychiatrists, I don’t see psychiatrists or primary care doctors as enemies in any way. They are good people trying to do a good job under very, very difficult circumstances, and they are often victims of a larger structural system, as are the people who come to them for help. The psychiatrists I have talked to are interested in the analysis that I do, an analysis in which I try to go beyond blaming a psychiatrist or a hospital and in which I examine the structural reasons that have led us to this situation. And I think that’s interesting for a lot of psychiatrists. They may agree or disagree with my argument, but most seem to me to be sympathetic to the analysis and its intent. Besides,

Has the pandemic made it more evident that we need a paradigm shift?

I think so. I think that the pandemic has shown the extent to which circumstances, relationships and situations affect mental health, and that narrative has been reinforced because the entire population has had a change in circumstances that for many people has had a strong impact on the way they feel and function. The social model of anxiety and stress has gained credibility as a result of what we have seen. And we’ve also seen more people acknowledge that medicalizing distress not only doesn’t solve the problem, it’s not feasible. In the UK, for example, there has been a strong push to demedicalise distress and stress because the health service is unable to deal with it. For the first time in 40 years, major bodies like England’s Public Health said: ” Your anguish and stress are not medical problems. Don’t come to us, our hands are tied. We have too many people right now, it’s a social problem. It’s just the opposite of what we’ve been told for a long time. More credence is being given to new narratives now, let’s see how that evolves.