Locked up, why? She had been deprived of her liberty simply because she was somewhat confused and had played loud music late in the evening. A neighbour had called the police, who found her home messy and requested her to be examined. She was not psychotic, and did not believe she needed professional assistance. She knew well what could happen, she had been locked up in a psychiatric ward some years ago. She was nevertheless taken to the local psychiatric hospital where she was locked up an hour later.

She had not committed any crime, wasn’t suicidal nor dangerous to anyone. The 45-year-old woman was known to her friends as a peaceful Christian and active in her community. But sometimes her life got a little too rattled and this was the case here. She knew she needed a chill out and so was going on holiday, and was playing music while packing for her trip the following day. Her mind was a bit somewhere else when the police rang the bell for the second time that evening. She couldn’t explain it away and ended up in the closed psychiatric ward.

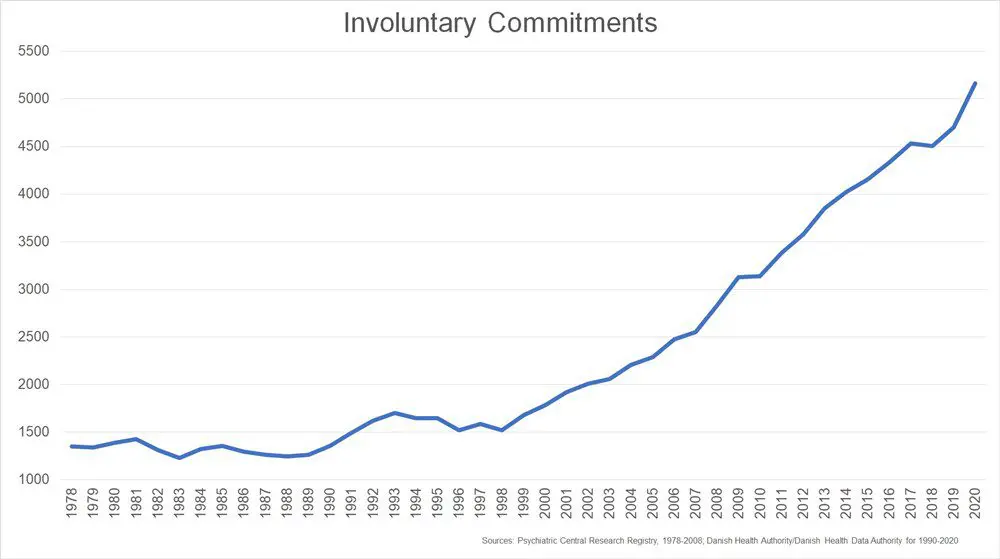

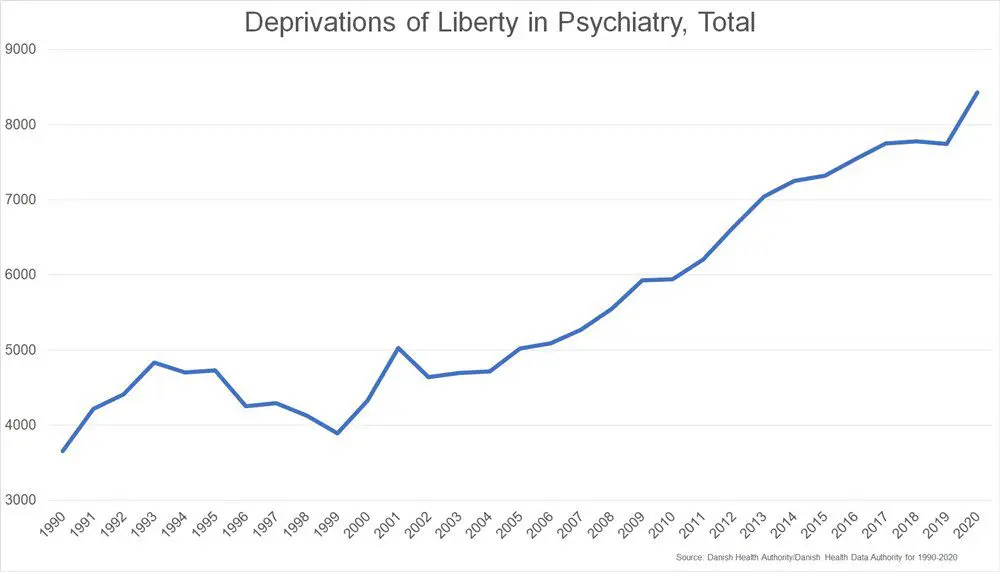

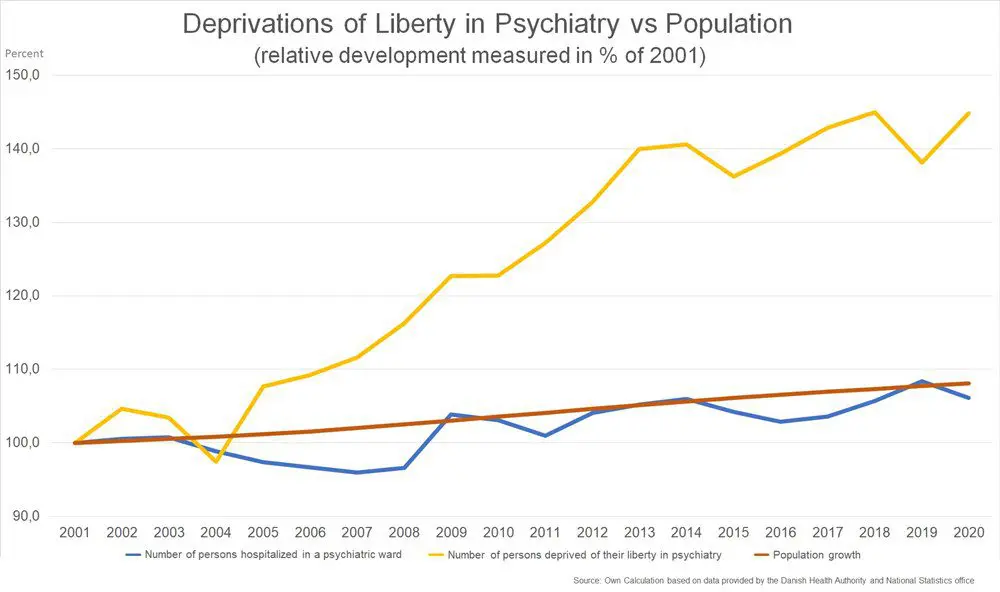

The above story may not be unusual in Denmark, as more and more people are being locked up in psychiatric wards. And it is not only happening to dangerous insane criminals, it happens to a wide number of persons. Despite a restrictive law, explicit safeguarding protocols, and a clear policy of reducing the use of coercive measures in psychiatry, last year saw the highest number of persons being deprived of their liberty in psychiatry. And it has been steadily increasing for years.

The Psychiatry Act

There are several ways a person can be deprived of his or her liberty in psychiatry in Denmark. The circumstances, criteria and safeguards against abuses are laid out in the special law, the Psychiatry Act. Deprivation of liberty and the use of coercion or force may be applied when it is not possible to obtain the person’s voluntary cooperation and the intervention is considered to be in accordance with the minimum means principle [less intrusive intervention].

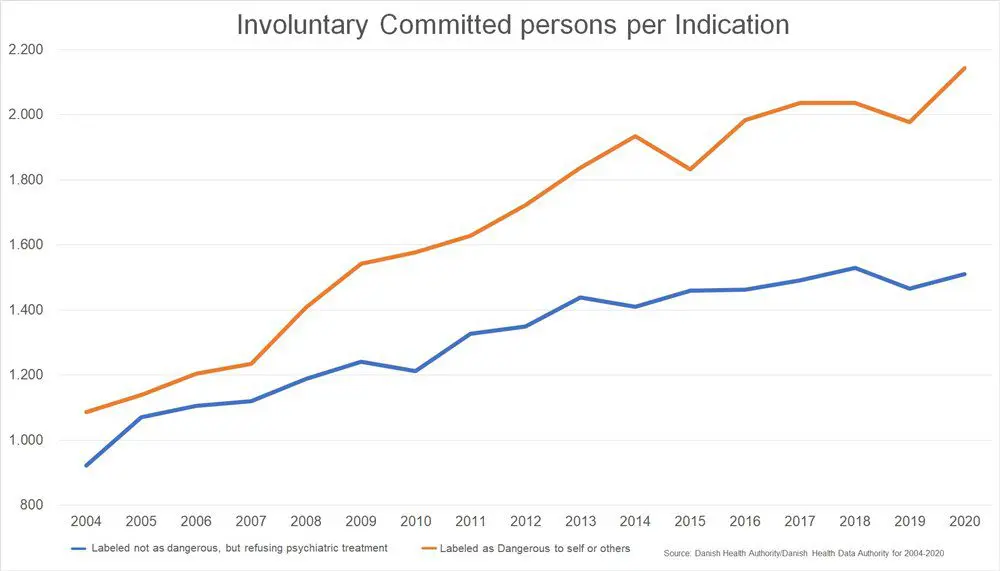

The law require that a person can and must be detained if he or she is in need of treatment, will not voluntarily accept an offer of admission and the following conditions are met:

- the person is insane or in a state corresponding to insanity and

- It is unreasonable not to detain the person in order to provide treatment because: (a) The prospect of recovery or of a significant and decisive improvement in the illness would otherwise be substantially impaired; or (b) The person poses an imminent and substantial danger to himself or others.

No court hearing is to be held for the deprivation of liberty to be legal. It can be executed the moment a psychiatrist has confirmed that according to his opinion the treatment that he believes he can provide is necessary. The subjected person can complain, but this does not prevent the execution of the deprivation of liberty.

This has led to an ever-increasing use of this means effectively detaining thousands of persons every year.

Eugenics

The possibility to target such a wide range of persons with the serious intervention – deprivation of liberty – has its roots in the 1920s and 1930s, when eugenics became a prerequisite and an integral part of the social development model in Denmark. At that time more and more authors expressed the wish that even non-dangerous “deviants” could be forcibly admitted to a mental facility.

The driving force behind this idea was not a concern for the individual, but a concern for society or the family. An idea of a society where the “deviant” and “troublesome” elements had no place.

According to then renown Danish Public Prosecutor of the Supreme Court, Otto Schlegel, in an article of the Danish Weekly Journal of the Judiciary, all the authors, except one, thought that “the possibility of compulsory hospitalisation should also be open to some extent to persons who are probably not dangerous but who cannot act in the outside world, the troublesome insane whose behaviour threatens to destroy or scandalize their relatives. Curative considerations have also been thought to justify compulsory hospitalisation in certain cases.”

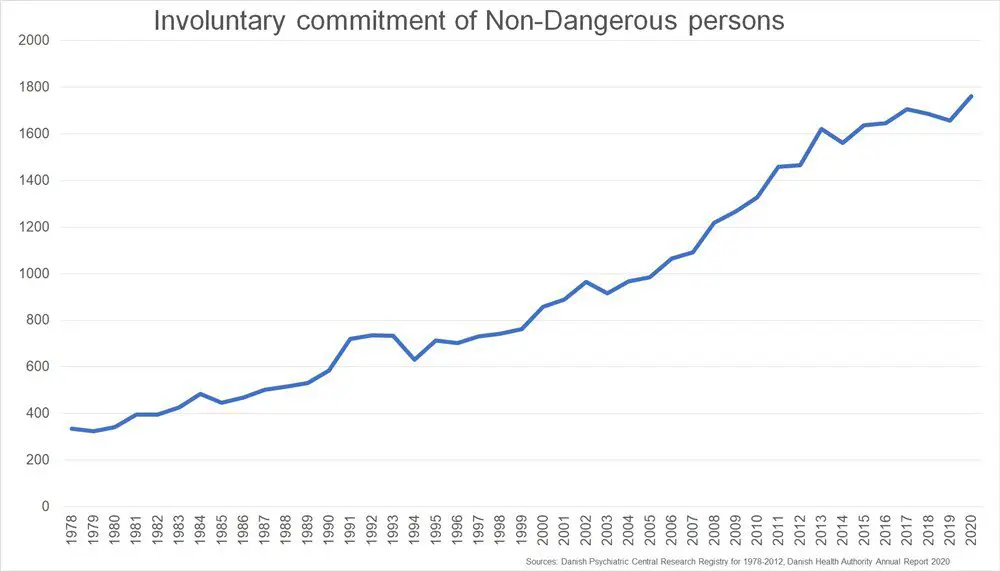

Thus, the Danish Insanity Act of 1938 introduced the possibility of detaining non-dangerous insane persons. The driving idea behind the idea of depriving the concerned of his or her liberty, and thereby removing those who could not function adequately in society – the so-called troublesome and deviant insane who was not dangerous – was not a concern for the individual, but a concern for society. It was not a compassionate concern or an idea of helping people in need that led to the introduction of this possibility in the legislation, but an idea of a society in which the deviant and “troublesome” elements had no place. After all, their behaviour could threaten to destroy or scandalize their relatives.

The deprivation of liberty of the insane was historically based on a principle of emergency law. Up to 1938, the legal basis for depriving the insane of their liberty was still to be found in Danish Law 1-19-7 of 1683 and in later legislation. The rules on the deprivation of liberty of the insane covered only insane persons who might be considered dangerous to the general safety or to themselves or their surroundings.

With the eugenics influenced Insanity Act of 1938 this changed, and the possibility to detain non-dangerous persons who are being pointed out as a societal trouble case has been maintained since in the newer Psychiatry Act.

Retainments

Deprivations of liberty in to psychiatry in addition to picking people up in their homes or from the street can also be done to persons who voluntarily hospitalize themselves.

If a person who admitted himself to a psychiatric hospital request to be discharged, the senior physician must decide whether the patient can be discharged or must be forcibly retained. The person’s wish to be discharged may be explicit (he or she demands to be discharged), but it may also be a behaviour of the person which must be equated with a wish to be discharged.

According to the law a voluntarily admitted patient can and must be detained if the person requests discharge at a time when the he or she meets the conditions for compulsory admission under the Psychiatric Act.

Prior to this, the patient’s consent to continued voluntary admission shall be sought in accordance with the principle of minimum means.

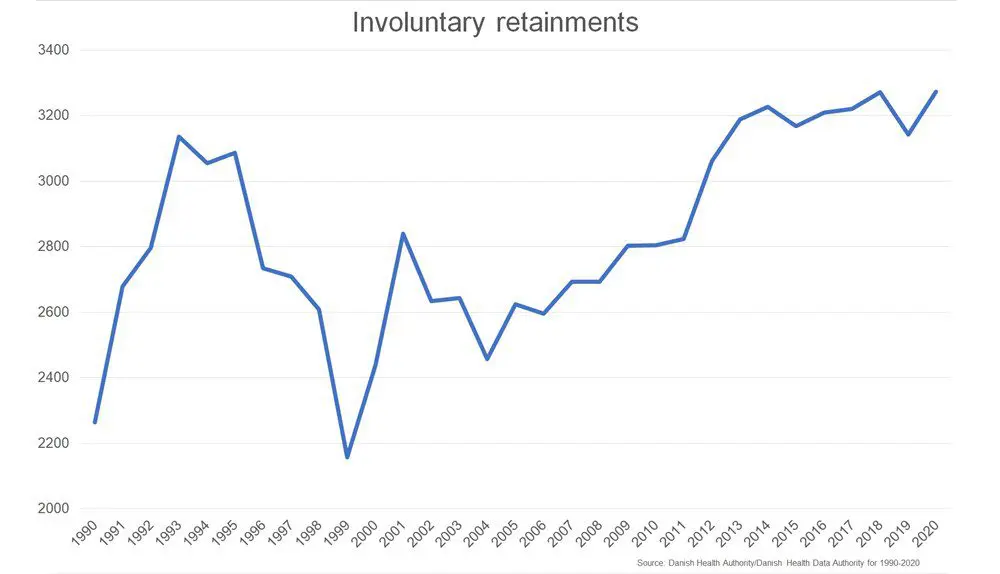

For more than 25 years there has been a very pronounced political and governmental will to decrease the use of coercion in psychiatry in Denmark. Yet, this intention is not reflected in the daily life and practice in the psychiatric wards. Thus, one also notes a significant increase of involuntary retainments.

In addition to the regular involuntary commitments and retainments, there is yet another less obvious procedure that is used to enforce commitments in to psychiatric wards without it appearing as an involuntary commitment, despite it is against the consent of the person concerned. This is court ordered convictions to psychiatric treatment according to the Criminal law. Thousands of persons today thus live in society but can be picked up at any time they would not follow treatment instructions and locked up in a psychiatric ward. When this is done, it is not considered an involuntary commitment.

Law causing coercion

The deprivation of liberty in to psychiatry is increasing year by year over the last decades and is far in excess of the psychiatric inpatient increase or population growth.

With the efforts of shifting Danish governments and the unanimous political intention to decrease the use of coercive measures in psychiatry, the allocation of resources and central administrative efforts to effectuate this one can only see the mere fact of the existence of the legal possibility to use or require the use of coercion as the reason for the sliding practice, with increasing deprivations of liberty in psychiatry.