In the Acts of the Holy Apostles, and also in the Epistles of St. Apostle Paul to the Romans and the Philippians contains information that does not correspond to their interpretation adopted by the Greek and Roman Catholic Churches. Moreover, they outline the beginnings of Christianity in Europe in a way that does not correspond to the ideas imposed by the East and the West.

Despite the differences between them, the two churches show complete unanimity in the presentation of related events, the consequences of which are reflected in the misinterpretation of the facts and their manipulation.

According to the Acts of the Apostles (16: 9-40), a “Macedonian man” appeared to the apostle as a vision and begged him, “Come into Macedonia and help us!” Paul understands that the Lord has commanded him to preach. there the Gospel and the very next morning he set out with the Apostle Silas for Macedonia. The two boarded a ship and one day they were on the island of Samothrace. And the next day they arrived in the port city of Naples (now Kavala). From there, the two went to Philippi, “the first city of Macedonia – a Roman colony.” The events that followed the arrival of the two in the city are described in detail in the account of the Acts of the Apostles. They are related to the first sermon that the Apostle Paul delivered the following Sabbath to the assembled multitude of women “by the river.” There he baptized one of them named Lydia, which marked the beginning of the first Christian community in Europe. This is also where the apostles’ first conflict with local authorities took place.

The masters of a slave girl, possessed by an evil spirit, whom Paul banishes, seize the two and take them to the market place, where the seat of the princes (archons). The two were slandered in front of the local chiefs (in the Greek original they were called στρατηγοί, and the Bulgarian or Church Slavonic translation gave them the name “voivodes”) that they rebelled against the people, and on their orders Paul was publicly beaten, after which he and Silas are chained and thrown into prison. During the night there was an earthquake, from which the doors of the dungeon opened and the shackles of the prisoners fell. The jailer is very impressed by this event and wants to be baptized with his family. In the morning, frightened by the events and the fact that Paul and Silas were Roman citizens and therefore could not be judged by them, the chiefs came to the dungeon to apologize to them and led them out of the city.

For the truth of the story of the Apostle Paul’s first journey to Europe, as well as for his fulfillment of the task assigned to him, namely to visit the country of the Macedonians and help its people by passing on the good news of Christ’s teaching, we we have no reason to doubt. Later, in his Epistle to the Romans (15:19), Paul explicitly confirmed the fulfillment of this task by saying that he “handed over the teachings of Christ to Illyricum.”

Only the interpretation of this story is questionable, as it is accepted and established by the tradition of the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox Churches. According to this tradition, the journey of the apostles Paul and Silas is to the small and insignificant city of Philippi, located only 15 km from Kavala.

However, we find a contradiction between the story and its interpretation when we mention the purpose of the trip: the country of the Macedonians, not the administrative unit called Macedonia, where, according to all commentators of the text, the missionary journey of the Apostle Paul takes place. But there is also a contradiction in the first sentence, which says that Philippi was “the first city of Macedonia – a Roman colony.” However, this is not true, because the first city in the country of the Macedonians is not Philippi, which is not the first city visited by the Apostle Paul in Europe, because this city is Naples / Kavala, nor the first city of the province of Macedonia, which is Amphipolis. .

Although this contradiction has been noticed by some historians who interpret it as exaggerating the importance of the city in connection with the mission of the Apostle Paul, the other circumstances related to this and his next trip to this city, as well as the contradictions related to their clarification , remain unnoticed or deliberately concealed by researchers. And this applies above all to the institutions of the Roman administration – the seat of the prince and the prison, which did not exist in the small town of Philippi – but above all the river mentioned in the story, which played an important role in the first and second journey of the Apostle Paul ( Acts 20, 6).

On their first journey, Paul and Silas go to the “river by the city” on the Sabbath, hoping to find a Jewish house of prayer there; there they meet a woman named Lydia, who was the first to receive holy baptism from the Apostle Paul on European soil. Here we must recall the importance that the Christian tradition attaches to the primacy, reflected in the titles “first martyr”, “first apostle” or “first called”. This woman and the jailer’s family became members of the first Christian community on the European continent.

But the river also played an important role in the apostle Paul’s second trip to Macedonia. When he learns that the Jews want to kill him during his voyage to Troy, he refuses to go by sea and chooses the much longer river route through Macedonia, boarding a ship in Philippi and sailing for Troy, where he arrives after five-day trip. All this is stated in the account of the Acts of the Apostles simply and clearly. But there is no river in Philippi – and there never was – in which ships have sailed and which has meanwhile dried up!

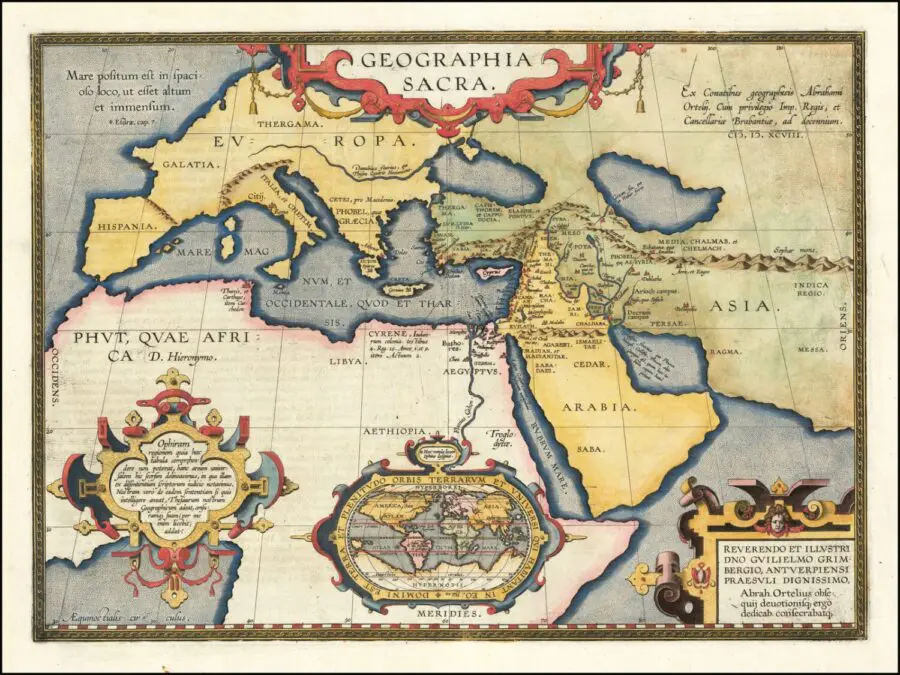

Throughout antiquity and until the Middle Ages on the Balkan Peninsula there were only two navigable rivers – the Danube and the Maritsa (Heber), from whose name derives the Greek name of our continent. And as is well known, on this river was located Philippopolis – or in Bulgarian Plovdiv. And from this city he traveled along the river for five days to Troy – as long as it took the apostle Paul to return. Although the first researcher to dedicate an extensive monograph to the city of Philippi, the Greek author Mercidis, noted in his work that in the past the names of Philippi and Philippopolis were often mixed, in the case of the two journeys of the Apostle Paul there can be no question of accidental error.

The Apostle Paul embarks on his journey to the “land of the Macedonians,” not to the Greeks or the Romans – and he was clearly able to distinguish both the population and the lands in which he lived. And in this sense, Philippi does not meet the purpose of his journey, because after “the most terrible battle of Caesar’s time and of all antiquity in general,” as some authors call what happened to Philippi in 42 BC. a battle between the armies of the assassins of Julius Caesar, Cassius, and Brutus, on the one hand, and of Octavian Augustus and Antony, on the other, the city and its environs were completely devastated and repopulated by Roman colonists.

The apostle Paul’s sermon “by the river” was not before the Romans, but before the locals, and the conflict in which he and Silas were involved was with the representatives of the provincial Roman government, as there was in the big city of Philippopolis – unlike the small town Philippi, in which we can look for neither a prince, nor a court, nor a prison. But Philippopolis is located in the neighboring province of Thrace, not in Macedonia, although it bears the name of the Macedonian emperor.

And what can the Thracians and the Macedonians have in common with the teachings of Christ, which in theological literature it is claimed that the Apostle Paul preached to the Jews, Greeks and Romans, but not to the population in the central part of the Balkan Peninsula?

The question of the ethnic origin of the Macedonians and Thracians and what territory they inhabited is as old as historical science – but it was Herodotus, who was the first historian to ask it, who also gave a very clear answer. And after more than two and a half millennia of controversy, what he says on the subject is the only thing that is known positively about them. That is, their ethnic origin and the language they spoke were different from those of the Greeks and they inhabited different territories – although there are authors who claim that their languages were too close, and even that the Macedonians spoke in some Greek dialect, and that the land on which they lived was Greek.