The ecumenical Patriarch Jeremiah II comments on the Confession of Augsburg

The 25th September 1559 Philipp Melanchton wrote in a circular letter to a number of friends, that he the very day had dispatched a letter to the Patriarch of the church of Byzans – the spiritual head of the orthodox churches.

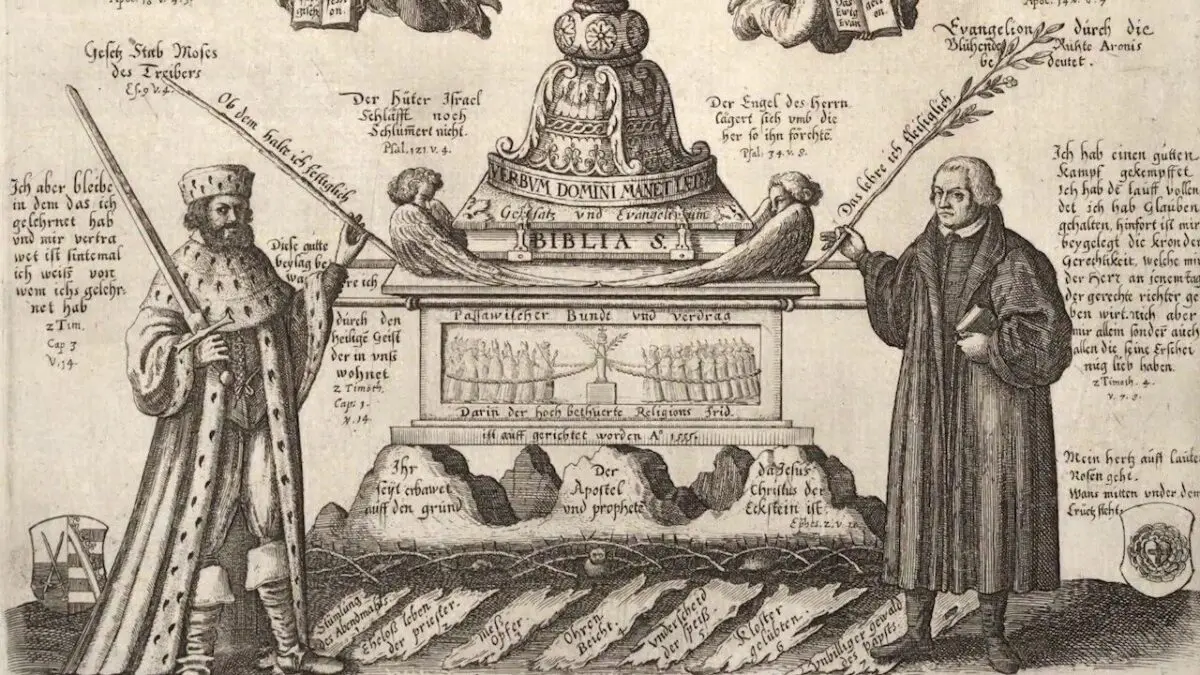

With the letter he also sends an interesting enclosing, “an essential document”, he writes. This essential document is nothing less than a translation into Greek of “the confession of our church” – that is the Confession of Augsburg.

In his letter(1)Melanchton takes for granted the widespread belief of the time of the Reformation in the imminence of the Day of Judgment and that only “repentance and inner renewment in the body of Christianity can help” in that state of things. East and West are connected and equally afflicted by the certain signs of the end of the world. The Greek church already has been overrun by the Turks – who without hesitation are identified with the apocalyptic people of Gog and Magog (Apoc. 20, 8). The West is under a constant threat from the same people and besides on the inner front from Papacy, which has raised its power in the middle of the temple of God.

The “messenger” who brings the letter and the confession is the deacon Demetrios, who has lived in Wittenberg in the house of Meælanchton from the 20th of May to the end of September. For three years he has been a deacon at the church in Constantinople and he is delegated by the Patriarch to get information about the movement of the Reformation. All this he gets in full during his stay at Melanchton and at the same time Melanchton gets reliable and actual news about the Orthodox Church now about 100 years after the conquest of Constantinople by the Turks.

Demetrios can from personal experience recount about the Lutheran Church, Melanchton writes, “That we in a god-fearing way stick to the holy prophetic and apostolic writings, the dogmatical decisions of the Holy Synods and the teaching of the Fathers”. The Lutherans also strongly dislike the Mohammedans and all enemies of God, who reject the holy church, including the self-made customs, which unlettered Latin monks have brought into the church. It is quite clear that Melanchton expects to meet the Orthodox Church by returning to the sources behind the medieval Roman church and its many abuses.

As a support for the oral account Demetrios gets the Confession of Augsburg in a Greek translation, done by Poul Dolscius, one of Melanchton’s pupils. In the preface to the first edition Dolscius takes his starting point in the miracleWhitsunday morning, where the apostles – being almost illiterates – by the outpouring of the Spirit get the highest possible linguistic education. What the apostles got through inspiration, the theologians and pastors of today have to reach the hard way through hard-working studies of the old languages: “Greek and Latin are the swaddling-clothes of the Godchild, the Son of Mary.” The translation of the confession and other Lutheran writings are going to serve acquiring knowledge of the Biblical languages – but still more it must underline the coherence between the Lutheran teachings and the Holy Scripture – down to the linguistic form.

The preface is omitted in the second edition and does not cover what we meet in the translation. It is not a mere translation of the Confession, as we know ir from the authorized edition from 1530 – but a very free version, which has the clear aim to make the Confession understandable for people belonging to another Christian tradition than the West-european, viz. The Greek/orthodox Church.

Many West-european expressions, marked by the legal language, which both the Roman Church and the Reformation used, is paraphrased and explained with expressions coming from the orthodox liturgy. On deciding places the text hardly is a translation, but rather a Greek rewriting of the Lutheran ideas and statements – using quotations from the Bible, expressions from the liturgy and words and topics from the Fathers.

Especially in the parts dealing with “Justification by Faith” and “Good Works”(2) we only find single words from the original text. Here the question is about interpreting and explaining in such a way that the content is loyal reproduced and really understood by the orthodox. The same can be said about the article of “original sin”(3), because the understanding of sin is decisive for the right understanding of justification by faith and the good works, as well. The Greek George Mastrantonis(4), who has worked seriously with the translation, reaches the conclusion, that “the translation of the Confession of Augsburg into Greek is a free translation, but without changing the intention of the writing”. It has been a really difficult task, linguistically and theologically, and the common opinion is that Melanchton has been adviser and consultant – surely helped by the deacon Demetrios – to be able to find the right formulation.

Melanchton gets no answer to his attempt to have a dialogue with the Orthodox Church. He does not hear from Demetrios or from the ecumenical Patriarch Josef II (1555 – 1565) and as early as 1560 Melanchton dies. The Greek dogmatist Ioannis Karmires in his dogmatics(5)is of the little malicious opinion that the reason could be that the patriarch found so many interpretations alien to the old church that he preferred to stay silent. It is complete guessing. Nobody knows what happened to Demetrios or his message – but a more likely guess is that Demetrios lost his life on the way to Constantinople – and so the letter never reached its recipient.

But the story does not end up here. 14 years later Lutheran theologians from the university of Tübingen picked up the thread – headed by the chancellor Jacob Andreae and the professor in Greek Martin Crucius. And this attempt succeeded. Now the dialogue got started and became that comprehensive that it with modern words became the first “joint commission” between the Lutheran Church and an alien church. With the difference that all work in the commission was in writing without oral meetings at all.(6)

This time the messenger was the pastor of the legation in Constantinople Stephan Gerlach. He was educated at the university in Tübingen and later became a theological professor at that university. He had the direct contact with the support base home and was personally present in Constantinople, where he without delay succeeded in getting contact with the patriarchate and the patriarch, Jeremias II. The 15th of October he was introduced to the patriarch and handed over the message, which he brought from Tübingen: Two private letters from Martin Crucius and Jacob Andreae and also a sermon written by Jacob Andreae about “the Good Shepherd” – text St. John 10, 11. After a short time supplemented by letters and a sermon more “The Kingdom of God has come close at hand” – text St. Luc. 10, 9. The patriarch commented rather elaborately upon these letters and sermons and ended up with a firm warning to the Lutherans: “We are not allowed to listen to the voices of strangers, who are going to introduce new doctrines, who have not entered through the door of the Gospel and the teaching of the church and the holy Fathers and teachers.”

But previous to the arrival of the Patriarch’s letter the Germans had taken the next step, sending the Patriarch an additional letter with the Greek translation of Confessio Augustana enclosed – ” a summary of the old faith, which has come down to us from Paradise.” And the forwarded letter continues as an answer to the Patriarch’s letter, which crossed the sending of the Confession of Augsburg: ” … we hope that we in no way have invented new things in the context of the articles, which concern the salvation, as we (as far as we can estimate) have observed and kept to the faith, which has been handed over from the holy apostles and prophets, from the Fathers and patriarchs, who were inspired by the Holy Spirit, and the seven ecumenical councils based upon the God-given writings.”

You may be surprised that the two Lutherans include also the seventh council, which exclusively deals with holy pictures and the veneration of icons, but it is important to notice the limitation contained in at the end of their letter: All statements have to be measured by the Holy Scripture – interpreted by the Lutherans. Later we shall see that this statement becomes one of the main points in dispute in the following dialogue.

The Lutheran confession was presented to the patriarch the 24th of May 1574 and he set up a committee composed of the leading Orthodox theologians. After procuring several additional copies of the confession, the commission was at session until the 15th of May 1576, when it made an elaborated answer in writing, which immediately was sent to Tübingen. The answer consists of nearly 50 pages and deals with every single article in the confession attaching great importance to expound the orthodox point of view to every question simultaneously indirect commenting on the Lutheran statements.

There are very few direct critical remarks – more exactly only concerning “faith and good works” and very decisive about “tradition”. In the concluding remarks of the document the orthodox opinion is clear and unambiguous expressed: “All here said, my beloved ones, is – as you very well know – based upon the inspired Holy Scripture, according to the interpretation of the Fathers of the Church, explanation and sound teachings. We are not allowed to trust our own interpretation and understand and interpret the words from the inspired scripture without consent with the Fathers of the Church, who are recognized by the holy synods, inspired by the Holy Spirit … ” In most cases the criticism is formulated indirectly as an invitation to further discussions not going into details about the Lutheran formulation – but by formulating in full the Orthodox attitude to the questions.

The answer from the Lutheran theologians, which is sent the 18th of June 1477, tries to systematize the rather diffuse impression, which the answer from the patriarch has left. They summarize the answer in six questions, where three are really controversial: “the Free Will”, “Faith and Works”, and the question about “Holy Scripture and Holy Tradition in the Church”, which is crucial for the Orthodox. The argumentation of the Lutherans are built upon quotations and interpretations from the Bible, but beautifully supplied with quotations from the Church-fathers, but it is underlined that “every man can make mistakes” – consequently also the Fathers of the Church. And who decides, whether an interpretation is in agreement with Holy Scripture? The Lutherans answer. “No better way is found than the way that Holy Scripture is interpreted by Holy Scripture – that is by or through itself. ” For the Orthodox it was only another word for one’s own more or less shrewd thoughts and ideas.

In May 1579the second answer of the Patriarch follows. In spite of many kind words about agreement in faith the tune changes in a renewed underlining of the critical attitude of the Lutherans against the Fathers of the Church and holy tradition. In short the Lutheran interpretation of the Bible, which has no foundation in fact. This fundamental disagreement makes the apparent unity in a number of details indifferent.

The Lutherans answer back the 24th of June 1580 by repeating the former arguments in a more rigorous form unable to understand that it was the foundation of the arguments “the Sola Scriptura”, which made the negotiations reach an impasse. It appears very clearly from the third and last answer from the patriarch: “We have considered keeping silent and not forward further answer to you, who twist the Holy Scripture and the interpretation of the Fathers in accordance with your own wishes. .. Do not write further about questions of doctrine, – however we should be happy to exchange letters for the sake of friendship.”

It became a voluminous work, when the total correspondence in 1584 was published in Wittenberg – nearly 300 pages. The Lutherans have not since picked up the thread, but in the Orthodox world the correspondence has got authoritative character, as the answers of the patriarch are looked at as one of the “confessions” of the Orthodox Church – with with reference to the Lutheran heresy. Still the 161 pages long letters of the patriarch form part of the symbolic books of the Orthodox Church, and Orthodox theological students have to go through this more than 400 years old dialogue between the Orthodox and the Lutherans.

Two questions are different and decisive; The importance of the tradition of the Church has been underlined in the preceding pages – and next the question of about the view of human nature, gathered in considerations about Free Will, the Fall of Man and the Original Sin, which again influence the view upon “faith and good works. – as the patriarch says in his last letter: The Orthodox Church does not believe in justification by faith alone, but in justification by faith, which produces good works through love.

Two questions and on the whole an ecumenical dialogue, which it would be profitable for both parts to take up again in the light of the development through more than 400 years, which have gone since the last letters were sent between Constantinople and Wittenberg.

Notes:

1) The letter is reproduced in Ernst Benz: Wittenberg und Byzanz, Kyrios IV.

2) The Confession art. 4 and 20.

3) Art. 2.

4) George Mastrantonis: Augsburg and Constantinople, Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1982.

5) Dogmatica et Symbolica Monumenta Orthodoxae Ecclesiae, auctore Ioanne Karmiris, 1968. Greek only.

6) The contributions both from the Lutheran and the Orthodox were published in: “Acta et Scripta Theologorum Wirtembergiensium et Patriarchae Constantinopolitani D. Hieremiae, quae utriqueanno MDLXXVI usque ad annum MDLXXXI de Augustana Confessione inter se miserunt, graece et latine ab iisdem Theologis edita” (Würtemberg 1584).

Literature:

“Acta et Scripta Theologorum Wirtembergiensium et Patriarchae Constantinopolitani D. Hieremiae, quae utrique ab anno MDLXXVI usque ad annum MDLXXXI de Augustana Confessione inter se miserunt, graece et latine ab iisdem Theologis edita” (Württemberg 1584).

(The publication is rare and almost inavailable. My copy is a microfilm-copy of the edition owned by the library of Union Theological Seminary i New York).

Stanislas Socolovius: Censura orientalia Ecclesiae de praecipuis nostri saeculi haereticorum dogmatibus. (Paris 1584)

Dogmatica et Symbolica Monumenta Orthodoxae Ecclesiae, auctore Ioanne Karmiris, 1968. (Greek only).

Georg Kretschmar: Die Confessio Augustana graeca. (Kirche im Osten 20/1977).

Paul Renaudin, O.S.B.: Lutheriens et Grec-Orthodoxes – Les erreurs du Protestantisme. (Librairie Bloud og Cie, Paris 1903).

George Elias Zacharides: Tübingen und Konstantinopel im 16. Jahrhundert. (Inaugural-Dissertation, Göttingen 1941).

Ernst Benz: Die Ostkirche – im Lichte der protestantischen Geschichtsschreibung von der Reformation bis zur Gegenwart. (München 1952).

Ernst Benz: Wittenberg und Buzanz – Zur Begegnung und Auseinandersetzung der Reformation und der östlich-orthodoxen Kirche. (Marburg/L. 1949).

Walther Engels: Die Wiederentdeckung und erste Beschreibung der östlich-orthodoxen Kirche in Deutscland durch David Chytraeus (1569).

Tübingen und Byzanz – Die erste offizielle Auseinandersetzung zwischen Protestantismus und Ostkirche im 16. Jahrhundert. (Begge i “Kyrios, 3/4, 1939).

George Mastrantonis: Augsburg and Constantinople (The correspondence between the Tübingen Theologians and Patriarch Jeremiah II of Constantinople on the Augsburg Confession). Holy Cross Orthodox Press, Massachusetts 1982.

Dorothea Wendenbourg: Reformation und Orthodoxie (Der ökumenische Briefwechsel zwischen der Leitung der Würtembergischen Kirche und Patriarch Jeremias II von Konstantinopel 1573 – 1581). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1986.

Colin Davey: The Orthodox and the Reformation. (Eastern Churches Review, Volume II, nr. 1 og 2, 1968).

George Florovsky: An early Ecumenical Correspondence. (World Lutheranism of Today, A tribute to Anders Nygren, Stockholm og Oxford 1950).