The question of icon-worship seems to be purely practical, given that icon-painting is a church-applied art. But in the Orthodox Church he received an extremely thorough, truly theological staging. What is the deep connection between Orthodoxy and icon-worship? Where the depth of communion with God can take place without icons, in the words of the Savior: “The time is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem” (John 4:21). But the icon depicts life in the age to come, life in the Holy Spirit, life in Christ, life with Heavenly Father. That is why the Church honors her icon.

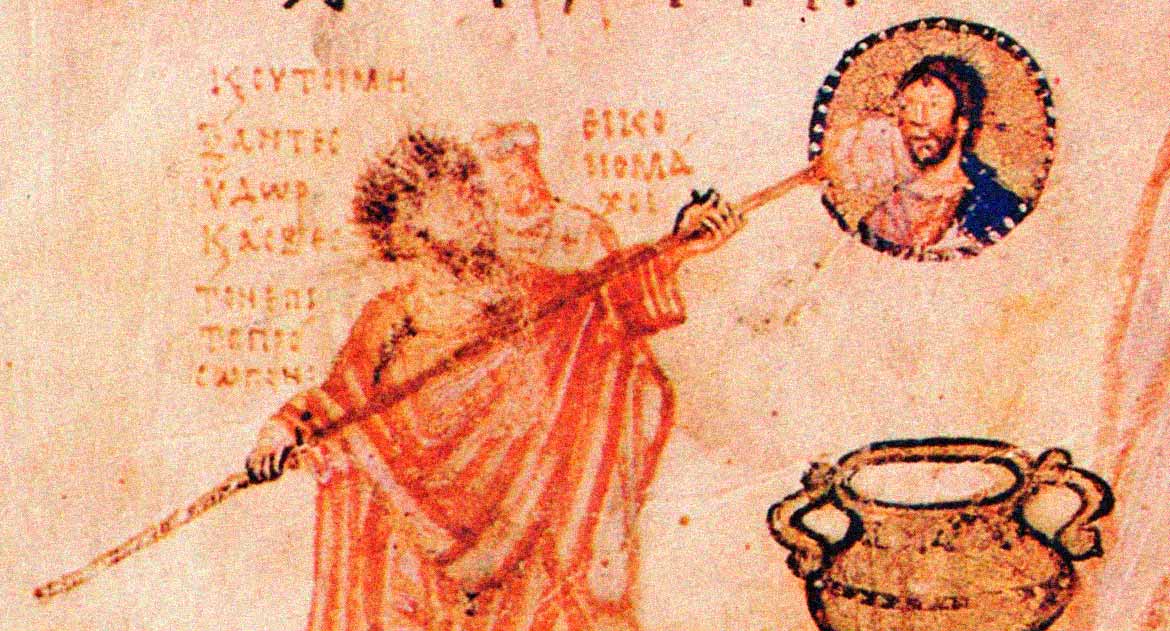

Iconoclasm (the struggle against sacred images) raised a long-standing question: the denial of icons had existed for a long time, but the new Isaurian, imperial dynasty in Byzantium turned it into a banner of its cultural and political agenda.

And in the first catacomb period of persecution, the hidden Christian symbolism appeared. Both sculpturally and picturesquely depicted the quadrangular cross (sometimes as the letter X), dove, fish, ship – all understandable to Christian symbols, even those borrowed from mythology, such as Orpheus with his lyre or winged geniuses who became subsequently typical images of angels. The fourth century, the century of freedom, brought into Christian temples already as generally accepted ornaments on the walls whole biblical paintings and illustrations of the new Christian heroes, martyrs and ascetics. From the relatively abducted symbolism in the iconography in the IV century, we decisively move to concrete illustrations of biblical and evangelical deeds and the depiction of persons from church history. St. John Chrysostom informs us about the distribution of images – portraits of St. Meletius of Antioch. Blazh. Theodoret tells us about the portraits of Simeon the Pilgrim sold in Rome. Gregory of Nyssa is moved to tears by the picture of Isaac’s sacrifice.

Eusebius of Caesarea responded negatively to the desire of the sister of Emperor Constantius to have an icon of Christ. The divine nature is inconceivable, «but we are taught that His flesh is also dissolved in the glory of the Godhead, and mortal is swallowed up by life … So, who could depict through dead and soulless colors and shadows the radiant and radiant shining rays of light of His glory and dignity? »

In the West, in Spain, at the Council of Elvira (now the city of Grenada) (c. 300), a decree was passed against wall paintings in churches. Rule 36: “Placuit picturas in ecclesiis es de non debere, ne quod colitur aut adoratur, in parietibus depingatur.” This decree is a direct fight against false iconoclasm, ie. with the pagan extremes in the Christian circles from which the fathers of the council were frightened. Therefore, from the very beginning there was a purely internal and ecclesiastical disciplinary struggle against iconoclasm.

Monophysitism, with its spiritualist tendency to diminish human nature in Christ, was originally an iconoclastic current. Even in the reign of Zeno in kr. In the 5th century, the Monophysite Syrian bishop of Hierapolis (Mabuga) Philoxenus (Xenaia) wanted to abolish icons in his diocese. Severus of Antioch also denied the icons of Jesus Christ, the angels, and the images of the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove.

In the West, in Marseilles, Bishop Seren in 598 removed from the walls of the churches and threw out the icons, which, according to his observations, were superstitiously revered by his flock. Pope Gregory the Great wrote to Seren, praising him for his diligence, inconsideratum zelum, but condemning him for destroying icons that serve the common people instead of books. The pope demanded that Seren restore the icons and explain to the flock both his action and the true manner and meaning of the veneration of the icons.

Emerging from the 7th century Islam with its hostility to all kinds of images (picturesque and sculptural) of human and superhuman faces (impersonal pictures of the world and animals were not denied) revived doubts about the legitimacy of icons; not everywhere, but in the areas neighboring the Arabs: Asia Minor, Armenia. There, in the center of Asia Minor, lived the ancient anti-church heresies: Montanism, Marcionism, Paulicianism – anti-cultural and anti-iconic in the spirit of their doctrine. For whom Islam was more understandable and looked like a more perfect, “more spiritual” Christianity. In such an atmosphere, the emperors, repelling the centuries-old onslaught of fanatical Islam, could not help but be tempted to remove the unnecessary obstacle to a peaceful neighborhood with the religion of Muhammad. It is not in vain that the defenders of the icons called the emperors-iconoclasts “σαρακηνοφρονοι – Saracen sages.” (AV Kartashev, Ecumenical Councils / VII Ecumenical Council 787 /, https://www.sedmitza.ru/lib/text/435371/).

The iconoclastic emperors fought with perverse enthusiasm with monasteries and monks no less than with icons, preaching the secularization not only of monastic estates but also of social life in all spheres of culture and literature. Inspired by secular state interests, the emperors were drawn to the new “secular” spirit of the time.

The iconographic canon is a set of rules and norms that regulate the writing of icons. It basically contains a concept of image and symbol and fixes those features of the iconographic image that separate the divine, upper world from the earthly (lower) world.

The iconographic canon is realized in the so-called erminia (from the Greek explanation, guidance, description) or in the Russian version-originals. They consist of several parts:

facial originals – these are drawings (outlines) in which the main composition of the icon is fixed, with the corresponding color characteristics; interpretive originals – give a verbal description of the iconographic types and how the various saints are painted.

As Orthodoxy became the official religion, Byzantine priests and theologians gradually established rules for the veneration of icons, which explained in detail how to treat them, what could and should not be depicted.

The decrees of the Seventh Ecumenical Council against the Iconoclasts can be considered the prototype of the iconographic original. Iconoclasts oppose the veneration of icons. They considered sacred images to be idols, and their worship to be idolatry, relying on Old Testament commandments and the fact that the divine nature is inconceivable. The possibility of such an interpretation arises, because there was no uniform rule for the treatment of icons, and in the masses they were surrounded by superstitious worship. For example, they added some of the paint to the icon in the wine for communion and others. This raises the need for a complete teaching of the Church about the icon.

The Holy Fathers of the Seventh Ecumenical Council gathered the church experience from the first times and formulated the dogma of icon worship for all times and peoples who profess the Orthodox faith. on a par with Him. The dogma of icon-worship emphasizes that the veneration and worship of the icon does not refer to the material, not to the wood and the paint, but to the one depicted on it, therefore it does not have the character of idolatry.

It was explained that icon-worship was possible because of the incarnation of Jesus Christ in human form. To the extent that He Himself appeared to mankind, His portrayal is also possible.

An important testimony is the non-manufactured image of the Savior – the imprint of His face on the towel (tablecloth), so the first icon painter became Jesus Christ himself.

The Holy Fathers emphasized the importance of the image as a perception and influence on man. In addition, for illiterate people, icons served as the Gospel. Priests were tasked with explaining to the flock the true way of worshiping icons.

The decrees also say that in the future, in order to prevent the incorrect perception of the icons, the holy fathers of the Church will compose the composition of the icons, and the artists will perform the technical part. In this sense, the role of the holy fathers was subsequently played by the iconic original or erminia.

Better white walls than ugly murals. What must be the icon to reveal the God of man in the 21st century? – What the Gospel communicates through words, the icon must express through image!

The icon by its nature is called to represent the eternal, which is why it is so stable and unchanging. It does not need to reflect what belongs to the current fashion, for example, in architecture, in clothes, in make-up – all that the apostle called “a transitional image of this age” (1 Cor 7:31). In the ideal sense, the icon is called to reflect the meeting and unity of man and God. In all its fullness, this union will be shown to us only in the life of the next age, and today and now we see “as if through a blurred glass, divining” (1 Cor. 13:12), but we still look into eternity. Therefore, the language of icons must reflect this union of the temporal and the eternal, the union of man and the Eternal God. Because of this, so many features in the icon remain unchanged. However, we can talk a lot about the variability of styles in icon painting in different eras and countries. The style of the era characterizes the face of one time or another and naturally changes when the characteristics of time change. We do not need to look for the style of our time on the way of any special works, it comes organically, naturally it is necessary. The primary search must be to find the image of man united with God.

The task of modern ecclesiastical art is to re-feel the balance that the fathers of the ancient councils wisely established. On the one hand, not to fall into naturalism, illusoryness, sentimentality, when emotionality dominates, wins. But even if it does not fall into a dry sign, built on the fact that certain people have agreed on a certain meaning of this or that image. For example, understanding that a red cross in a red circle means a parking ban only makes sense when one has studied road signs. There are generally accepted “signs of visual communication” – road, orthographic, but there are also signs that for the uninitiated it is impossible to understand… The icon is not like that, it is far from esoteric, it is Revelation.

Excess in the external is a sign of defect / poverty of spirit. Laconism is always higher, nobler and more perfect. Through asceticism and laconicism, greater results can be achieved for the human soul. Today we often lack true asceticism and true laconicism. Sometimes we go beyond nine lands in the tenth, forgetting that the Mother of God always sees and hears everywhere. Each icon is miraculous in its own way. Our faith teaches us that both the Lord and the Mother of God, and each of our saints, hear our address to them. If we are sincere and turn to them with a pure heart, we always get an answer. Sometimes it is unexpected, sometimes it is difficult for us to accept it, but this answer is given not only in Jerusalem, not only in the Rila Monastery.

Orthodoxy can triumph not when it anathematizes those who sin, those who do not know Christ, but when we ourselves, including through the Great Canon of the Venerable Andrew of Crete, remember the abyss that separates us from God. And, remembering this, we begin with God’s help to overcome this abyss, “restoring” the image of God in ourselves. Here we must ask ourselves not the styles, but the image of God, which should be reflected within each of us. And if this process takes place in the depths of the human heart, then, in one way or another, it is reflected: by the icon painters – on the boards, by the mothers and fathers – in the upbringing of their children, by everyone – in his work; if it begins to manifest itself in the transformation of each individual person, society – then only Orthodoxy triumphs.