Artistic reconstruction of Paradoryphoribius chronocaribbeus gen. et sp. nov. in mosses. Credit: Original art created by Holly Sullivan

Tardigrades, also known as water bears, are a diverse group of charismatic microscopic invertebrates that are best known for their ability to survive extreme conditions. A famous example was a 2007 trip to space where tardigrades were exposed to the space vacuum and harmful ionizing solar radiation, and still managed to survive and reproduce after returning to Earth. Tardigrades are found in all the continents of the world and in different environments including marine, freshwater, and terrestrial.

Tardigrades have survived all five Phanerozoic Great Mass Extinction events, yet the earliest modern-looking tardigrades are only known from the Cretaceous, approximately 80 million years ago. Despite their long evolutionary history and global distribution, the tardigrade fossil record is exceedingly sparse. Due to their microscopic size and non-biomineralizing body, the chance of tardigrades to become fossilized is small.

In a paper to be published on October 6, 2021, in Proceedings of the Royal Society B researchers describe a new modern-looking tardigrade fossil that represents a new genus and new species. The study used confocal laser microscopy to obtain higher resolution images of important anatomical characteristics that aid in phylogenetic analyses to establish the taxonomic placement of the fossil.

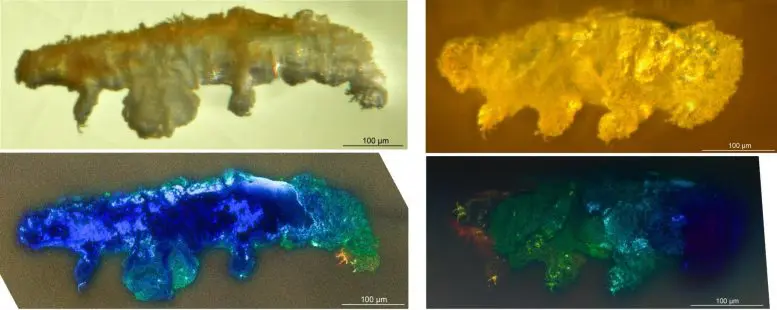

Left) Lateral view of Paradoryphoribius chronocaribbeus gen. et sp. nov. viewed with transmitted light under streomicroscope (top) and with autofluorescence under confocal laser microscope (bottom). Right) Ventral view of Paradoryphoribius chronocaribbeus gen. et sp. nov. viewed with transmitted light under streomicroscope (top) and with autofluorescence under confocal laser microscope (bottom). Credit: Images by Marc A. Mapalo

The new fossil Paradoryphoribius chronocaribbeus is only the third tardigrade amber fossil to be fully described and formally named to date. The other two fully described modern-looking tardigrade fossils are Milnesium swolenskyi and Beorn leggi, both known from Cretaceous-age amber in North America. Paradoryphoribius is the first fossil to be found embedded in Miocene (approximately 16 million years ago) Dominican amber and the first fossil representative of the tardigrade superfamily Isohypsibioidea.

Co-author Phillip Barden, New Jersey Institute of Technology, introduced the fossil to lead author Marc A. Mapalo, Ph.D. Candidate, and senior author Professor Javier Ortega-Hernández, both in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University. Barden’s lab discovered the fossil and teamed with Ortega-Hernández and Mapalo to analyze the fossil in detail. Mapalo, who specializes in tardigrades, took the lead in analyzing the fossil using confocal microscopes located in the Harvard Center for Biological Imaging.

“The difficulty of working with this amber specimen is that it’s far too small for dissecting microscopes, we needed a special microscope to fully see the fossil,” Mapalo said. Generally, the light transmitted by dissecting microscopes works well to reveal the morphology of larger inclusions such as insects and spiders in amber. Paradoryphoribius, however, has a total body length of only 559 micrometers, or slightly over half a millimeter. At such a small scale a dissecting microscope can only reveal the external morphology of the fossil.

Fortunately, Tardigrade’s cuticle is made of chitin, a fibrous glucose substance that is a primary component of cell walls in fungi and the exoskeletons of arthropods. Chitin is fluorescent and easily excited by lasers making it possible to fully visualize the tardigrade fossil using confocal laser microscopy. The use of confocal laser microscopy instead of transmitted light to study the fossil created degrees of fluorescence allowing a more clear view of the internal morphology. With this method Mapalo was able to fully visualize two very important characters of the fossil, the claws and the buccal apparatus, or the foregut of the animal which is also made of cuticle.

“Even though externally it looked like a modern tardigrade, with confocal laser microscopy we could see it had this unique foregut organization that warranted for us to erect a new genus within this extant group of tardigrade superfamilies,” said Mapalo. “Paradoryphoribius is the only genus that has this specific unique character arrangement in the superfamily Isohypsibioidea.”

“Tardigrade fossils are rare,” said Ortega-Hernández. “With our new study, the full tally includes only four specimens, from which only three are formally described and named, including Paradoryphoribius. This paper basically encompasses a third of the tardigrade fossil record known to date. Furthermore, Paradoryphoribius offers the only data on a tardigrade buccal apparatus in their entire fossil record.”

The authors note there is a strong preservation bias for tardigrade fossils in amber due to their small size and habitat preferences. Thus, amber deposits provide the most reliable source for finding new tardigrade fossils, even though that does not mean finding them is an easy task. The discovery of a tardigrade fossil in Dominican amber suggests that other frequently sampled sites, such as Burmese and Baltic amber deposits, could also harbor tardigrade fossils. Historically there is a bias towards larger inclusions in amber as inclusions as small as tardigrades are hard to see and require extremely good observational skills, as well as some specialist knowledge.

“Scientists know where tardigrades broadly fit in the tree of life, that they are related to arthropods, and that they have a deep origin during the Cambrian Explosion. The problem is that we have this extremely lonely phylum with only three named fossils. Most of the fossils from this phylum are found in amber but, because they’re small, even if they are preserved it may be really difficult to see them,” Ortega-Hernández said.

Mapalo agreed, “If you look at the external morphology of tardigrades, you might assume that there are no changes that occurred within the body of tardigrades. However, using confocal laser microscopy to visualize the internal morphology, we saw characters that are not observed in extent species but are observed in the fossils. This helps us understand what changes in the body occurred across millions of years. Furthermore, this suggests that even if tardigrades may be the same externally, some changes are occurring internally.”

Mapalo and Ortega-Hernández continue to employ confocal laser microscopy technology to study other tardigrades in amber in their hopes to expand the tardigrade fossil record.

Reference: “A tardigrade in Dominican amber” 6 October 2021, Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2021.1760