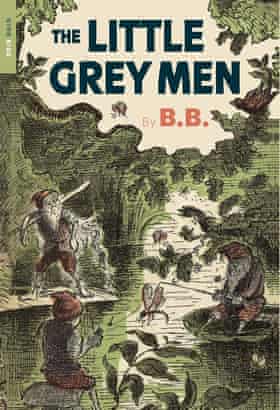

A couple of years ago I found myself gazing at the cover of a book I’d loved as a child: the 1942 Carnegie medal-winning The Little Grey Men, by the naturalist, illustrator and sportsman Denys Watkins-Pitchford, who wrote under the name BB. The charge it carried felt electric, and even opening the cover felt risky; I braced myself in case its magic had faded in the 40 years since it had been read to me at bedtime.

The Little Grey Men was published during the misery of the second world war, with destruction all around and a sense – familiar to us today – of a world in terminal decline. I remembered it as an utterly luminous evocation of spring, summer and autumn in the countryside, seen through the eyes of the very last gnomes in Britain: “honest-to-goodness gnomes, none of your baby, fairy-book tinsel stuff, and they live by hunting and fishing like the animals and birds, which is only proper and right,” as BB wrote. As a child I loved that businesslike tone, with its flattering dismissal of other, “babyish” stories; I loved BB’s illustrations, the precise and detailed rendering of the natural history in the book, and most of all the feeling it gave me of a secret world to which I was being granted privileged access.

I needn’t have worried. As I turned the pages I found myself enchanted all over again, and I began to think about the other nature novels I’d loved: Fiver, Hazel and Bigwig’s flight from ecological destruction in Richard Adams’s Watership Down; the glorious Devon riverscapes of Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter; Wulfgar gnawing off Teg’s paw to free her from a snare in Brian Carter’s A Black Fox Running. I could clearly see how those early animal stories had shaped my adult interests and sympathies, but when I tried to find modern books that might awaken children’s interest in nature – perhaps written by a more diverse range of voices than those I had grown up with – I was surprised by how few there were. Working in secret in case I couldn’t pull it off, I began to write By Ash, Oak and Thorn, an updated story inspired by, and in homage to, the magical world created by BB.

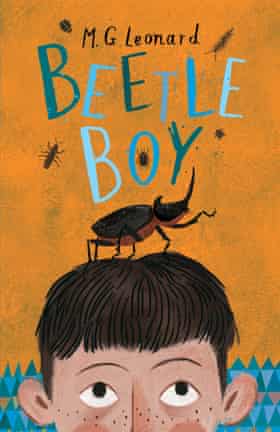

“I believe that the most powerful books a person reads are when they’re making decisions about the kind of human they want to be,” says MG Leonard, author of the bestselling Beetle Boy, Beetle Queen and Battle of the Beetles – all-too-rare examples of nature-based fiction for today’s children. “I write in the hope that my readers, once they’ve finished my books, won’t subscribe to the assumption that bugs are disgusting or terrifying, and will marvel at the amazing little creatures that run this planet.” Leonard’s books offer children a way of seeing the world and relating to other creatures – one that may prove vital in overcoming the ecological challenges we face.

Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden was the nature novel that changed Leonard’s life. “I read it several times as a girl and loved it, but it wasn’t until I was in my 20s and struggling with depression that the message hit home,” she recalls. “It was one of the reasons I began gardening; at first planting a window box of lavender, then, slowly, gathering containers of plants on the steps up to my flat, which brought the bugs, and they attracted the birds. It made me happy.” Books are tool kits: the things we learn from them can change our own lives, as well as the world.

The extraordinary success of Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris’s The Lost Words: A Spell Book is also proof of a growing hunger for writing that connects children to nature. It was created as a response to the Oxford Junior Dictionary’s decision to expunge dozens of nature words from its pages, and a way of celebrating those that had been culled. “Keeping everyday nature alive in the words and stories of children in particular – who are the ones who will grow up and decide what to save and what to lose – seems to me vital,” Macfarlane wrote at the time.

So what were the books he read as a boy? “Colin Dann’s The Animals of Farthing Wood series activated an early sense of the problems of human-animal conflict,” he says. “I got deep into Brian Jacques’s Redwall series, and like many people my age I still shudder at the memory of General Woundwort from Watership Down. I also pored over BB’s Brendon Chase, and details from it – including that honey buzzards scrim their nests with fresh beech leaves, as the young leaves contain a natural insecticide – are with me still.”

I fell in love with Tarka the Otter when I was too young to know anything about its author’s postwar PTSD, or his later fascism – as did the farmer and bestselling author of The Shepherd’s Life and English Pastoral, James Rebanks. “I was deeply affected by the beauty of the pictures Henry Williamson painted with words,” he says now, “and there was a radical aspect to its effect on me, because I was beginning to realise that if nature was beautiful and literary, then who saw it more directly than me, a kid who worked in fields all day long?” Portals, as well as tool kits: nature stories can leave marks that change lives.

Macfarlane makes the point that the books that first open the door to nature need not be fiction at all: “What we might call ‘field guides’ can be a form of imaginative literature, especially to a child’s mind. I still have, and still turn to, the Reader’s Digest Guides, which I bought with hoarded money and book tokens, about one a year: their combination of artwork, identifying ‘facts’ and a compressed poetry of description sharpened my eyes and fired my mind.” Helen Macdonald, author of H Is for Hawk, was also a fan of guide books: “They were full of characters that I could learn to recognise and name, and then, if I were lucky, strike out and see them living in the real world around me,” she recalls. Like me, she loved BB’s books, too: “I obsessed over Wild Lone, his biography of a fox; and Manka, the Sky Gypsy, about an albino pink-footed goose. I identified with the animals in their pages, and rooted for them as they went through all manner of perils.”

Not quite field guides, Ladybird’s classic and recently updated What to Look for … series, originally illustrated by the great Charles Tunnicliffe, left an indelible impression on generations of children. Mary Colwell, the author of Beak, Tooth and Claw: Living with Predators in Britain, is a conservationist and the campaigner behind the growing call for a natural history GCSE. “I felt grown up,” she says. “I had a different demeanour reading them than I did with books that were obviously for children. They awakened my serious mind. It was as though everywhere there were little eyes, sharp teeth and fluttery wings – and they were in the same place as I lived! I just had to look, and a cast of incredible characters would be revealed.”

David Lindo, an author, broadcaster and wildlife tour leader, was behind the poll to find Britain’s first national bird. Writing as the Urban Birder, he aims via his books, campaigns and events to connect a diverse range of people, from beginners to experts, to nature in towns and cities all over the world. In his case, it was conservationist Gerald Durrell’s memoirs that proved an early inspiration: “As a child I wasn’t read to at night nor encouraged to read fiction – but I did indulge in factual literature,” he says. “Reading My Family and Other Animals really fuelled my future lust for travel and discovery.”

Nature writing breeds nature lovers as well as writers. Bevis Watts was named after the child in Victorian nature writer Richard Jefferies’s wildly popular Bevis: The Story of a Boy. Watts has spent his life in environmental organisations, including as chief executive of Avon Wildlife Trust, and now as the chief executive of the ethical banking firm Triodos. “I was named in the hopes I’d have as good a life as the boy in Jefferies’s book, a life that had a close connection to nature,” he explains. “The importance and joy of spending time in nature and respecting it was the overwhelming message I grew up with.”

There has never been a shortage of books featuring animals, of course – they are a staple of children’s publishing from board books on, and stretch all the way back from Aesop to Babar the Elephant and Peter Rabbit. But these are often not the kind of nature books that inspire children. They are simply “ourselves in fur”, as the critic Margaret Blount put it.

One of the things we do to animals “is tame them”, writes Clare Pollard in the brilliantly illuminating cultural history Fierce Bad Rabbits: The Tales Behind Children’s Picture Books. “We also tame children. The similarity between these two processes does much to explain how common animals have become in picture books, especially farm animals or pets. We make these creatures walk upright, like circus ponies. We put Anubis in mittens and use him to teach three-year-olds how to behave.”

She is right, of course: I may have enjoyed the Babar books as a child, but it was stories about real animals in their own habitats, such as the vividly observed A Black Fox Running, that made me the writer and nature lover I am today – and made me want to inspire other children in turn.