Production of the compact SVDS model intended for special forces has increased 13 times compared to last year.

The Russian state concern Kalashnikov, the country’s largest small arms manufacturer, has announced a large-scale program to modernize the Dragunov (SVD) sniper rifle. The SVDS model is a compact version of the basic model with a folding stock, which has so far been used mainly by the airborne troops, marines and other elite units.

“The Kalashnikov concern has increased the production of 7.62-mm Dragunov sniper rifles with a folding stock (SVDS) 13 times compared to 2024. This is in response to increased demand in the area of special military operations,” the press service of the concern said in a statement, quoted by Russian media.

Although the SVDS barrel is a few centimeters shorter than that of the standard SVD (565 mm versus 620 mm), the weapon retains high accuracy and the ability to engage targets at distances up to 1,000 meters.

“The advantages of this rifle have been confirmed by three decades of successful operation. Semi-automatic action, compact design, low weight and high accuracy are undisputed advantages of the SVDS. It effectively helps our troops perform combat missions,” said the concern’s general director Alan Lushnikov.

The Dragunov rifle, designed by Yevgeny Dragunov in the 1950s, is a self-loading weapon designed to engage various targets at distances up to 1,200 meters. Technically, despite its name (“Dragunov Sniper Rifle”), it is not a sniper rifle in the classical Western sense, but rather a precision-shooting weapon in the infantry division (DMR).

Its purpose is to provide units with firepower at longer ranges than standard assault rifles, such as the AK-47 and its variants. Like the legendary assault rifle, the SVD is known for its exceptional reliability, ease of maintenance and operation, which makes it popular not only in regular armies, but also among various armed groups around the world.

The modernization includes changes to the folding stock, the addition of a Picatinny rail, and other optimizations based on lessons learned from the war in Ukraine.

In addition to the upgraded SVDS, Russian forces at the front are also receiving new supplies of the SV-98 manual-loading sniper rifles, which are intended for regular snipers.

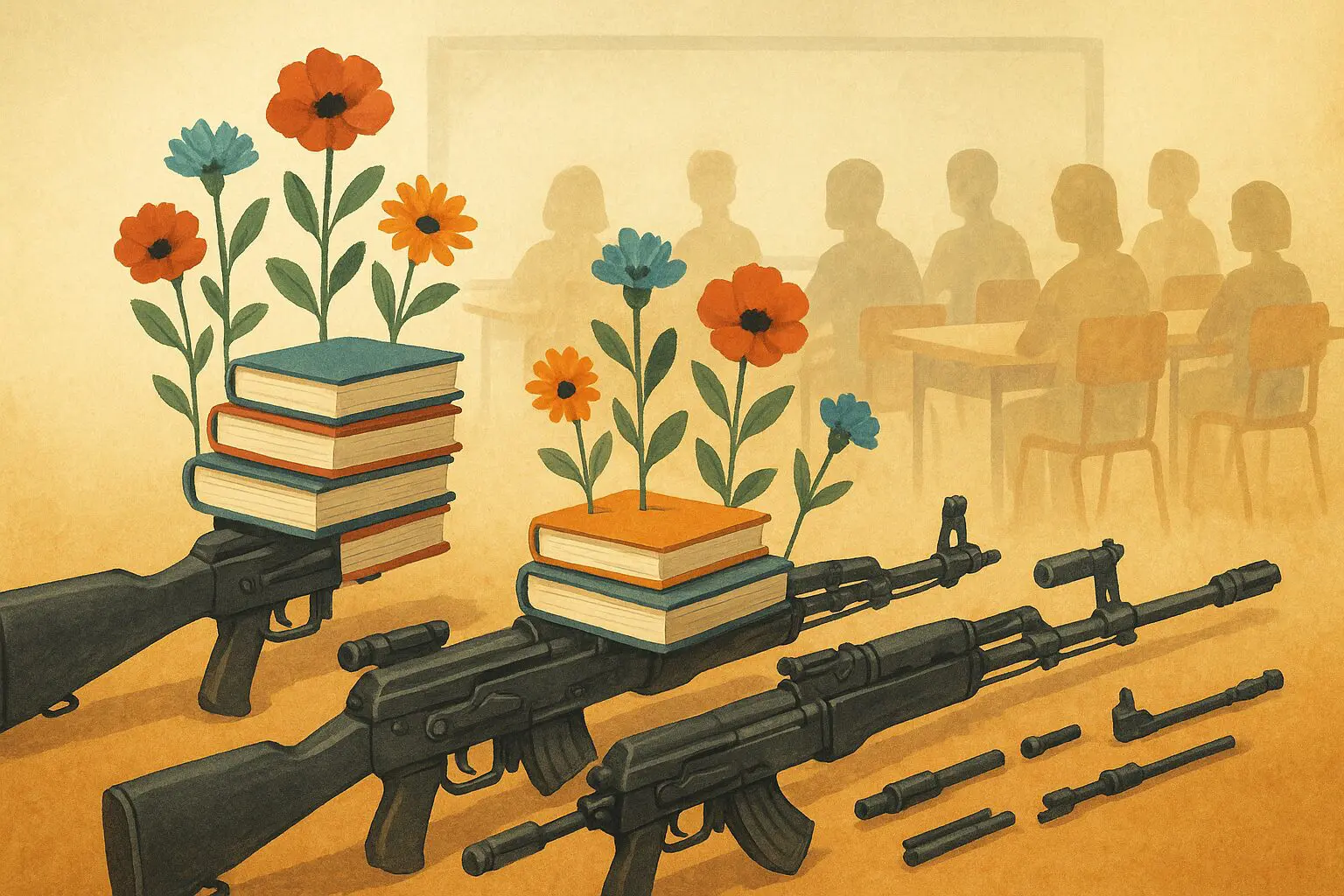

Russia boosts rifle output as education underfunded

Kalashnikov has increased production of its SVDS rifle thirteenfold, presenting it as strategic progress. The announcement raises a familiar question: why do weapons receive such extraordinary investment while education, social cohesion, and respect for diversity struggle to secure the same attention?

Mass production of a battlefield rifle

The Russian state concern Kalashnikov, the country’s largest small arms manufacturer, has confirmed a large-scale modernisation of the Dragunov (SVD) rifle platform. According to the company, production of the SVDS model — a compact version of the original Dragunov rifle with a folding stock — has grown thirteen times compared to last year.

“The Kalashnikov concern has increased the production of 7.62-mm Dragunov sniper rifles with a folding stock (SVDS) 13 times compared to 2024. This is in response to increased demand in the area of special military operations,” the company’s press service said, as cited by Russian media.

The SVDS is marketed as a specialised weapon for airborne troops, marines and other elite units. Its barrel is a few centimetres shorter than the standard SVD (565 mm versus 620 mm), but the manufacturer says it maintains high accuracy and can engage targets at distances up to 1,000 metres.

“The advantages of this rifle have been confirmed by three decades of successful operation. Semi-automatic action, compact design, low weight and high accuracy are undisputed advantages of the SVDS. It effectively helps our troops perform combat missions,” said Kalashnikov’s general director Alan Lushnikov.

A technically reliable weapon – and an old idea of security

The Dragunov rifle, designed in the late 1950s by Yevgeny Dragunov, is a self-loading designated marksman rifle intended to give infantry units reach at distances up to 1,200 metres. In military doctrine it is not a traditional Western-style sniper rifle, but a precision-support weapon to extend the range of regular units.

The SVD family has long been praised for reliability, ease of maintenance and relatively simple training requirements. These traits helped spread it not only through state armies, but also through armed groups around the world. In that sense, its “success story” is not only industrial. It is also a reminder of how easily a tool designed for long-distance killing can circulate far beyond state control.

Kalashnikov says the current modernisation includes changes to the folding stock, the addition of a Picatinny rail for optics and accessories, and other adaptations “based on lessons learned from the war in Ukraine.” Alongside the upgraded SVDS, Russian units are also reportedly receiving new batches of SV-98 manually loaded rifles for trained snipers at the front.

The cost of choosing rifles over classrooms

The scale and speed of this expansion in rifle output is striking. A thirteenfold increase in one year signals clear political and financial priorities. It also raises a broader question that is not unique to Russia: what kind of strength is being built, and for whom?

Across Europe, educators and civil society actors continue to argue that long-term security is not created by better optics and lighter stocks, but by investing in education, in dialogue, and in the ability to understand and live with difference. Work on democratic culture, civic ethics and respect for human dignity is repeatedly shown to reduce instability and radicalisation. This is true in classrooms, in local communities, and in the integration of newcomers and minorities.

That vision — of stability built on human development rather than firepower — is one that European institutions, human rights advocates and many educators continue to defend. Initiatives promoting inclusion, intercultural awareness and social responsibility are regularly highlighted as essential to peacebuilding, not as an accessory to it. The European press, including The European Times, has repeatedly documented that societies investing in civic education and social cohesion tend to be more resilient in the face of conflict.

Every surge in weapons production therefore comes with an invisible opportunity cost. Each rifle rolling off an assembly line represents public money, technical skill and political focus that could otherwise have supported teachers, youth programmes, scholarships, language training, conflict mediation or community projects that bring people together instead of pushing them apart.

Security measured by fear — or by understanding

Kalashnikov presents the SVDS expansion as proof of effectiveness and readiness. From an industrial point of view, it is. But it also reflects an older logic of security: one in which safety is achieved primarily through the threat of force.

Europe’s post-war vision, however, was built on a different idea. It held that preventing future conflict required teaching generations to respect human dignity, to understand differences before they become fault lines, and to resolve disputes through law and institutions rather than rifles. That vision is imperfect and still contested, but it remains the basis for peace on the continent.

The contrast today is sharp. One model sees progress in higher production of battlefield rifles. The other sees progress in classrooms where young people learn critical thinking, empathy and responsibility. One model prepares for the next confrontation. The other tries to make the next confrontation less likely.

The question is no longer technical. It is moral, civic and generational: do we train people to shoot at 1,000 metres, or do we train them to listen at one metre?