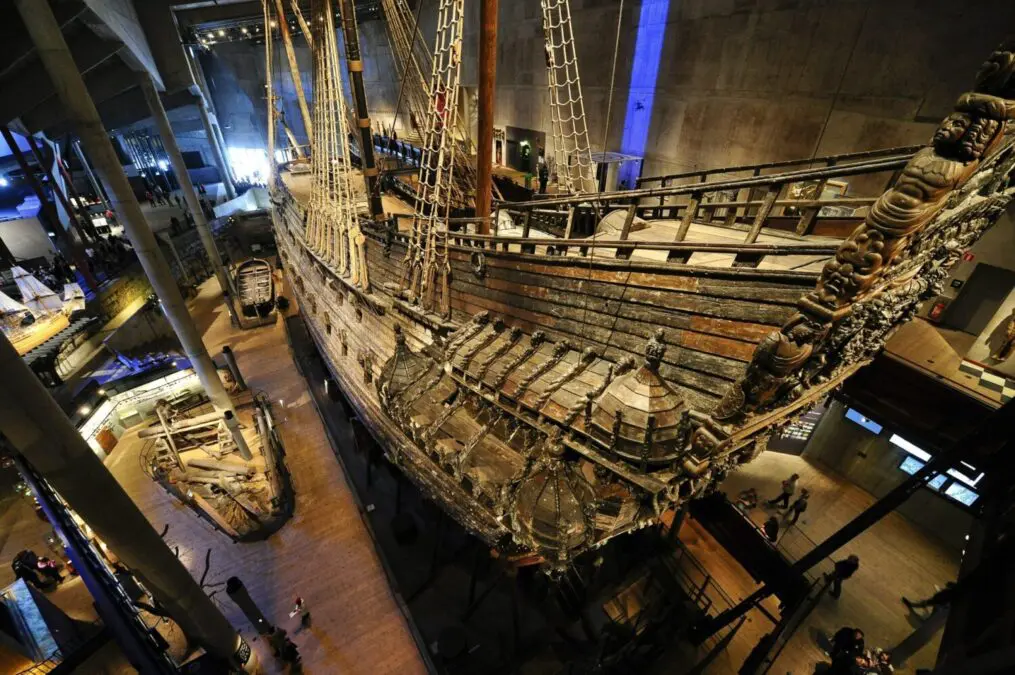

The wreck of the royal ship Vasa was recovered in 1961 and is remarkably well preserved after more than 300 years underwater in Stockholm harbor

An American military laboratory has helped the Swedes confirm what had been suspected for years: a woman was among the dead on a 17th-century warship that sank on its maiden voyage. This was announced last week by the museum where the ship is exhibited, AP reported.

The wreck of the Royal Warship Vasa was recovered in 1961 and is remarkably well preserved after more than 300 years underwater in Stockholm harbour. Since then, the ship has been housed in the Vasa Museum, one of the biggest tourist attractions in the Swedish capital, where visitors can admire its exquisite carvings.

About 30 people died when the Vasa capsized and sank just minutes after leaving port in 1628. They are believed to have been crew members, and the identities of most of them are unknown.

For years, there had been indications that one of the victims, known as “Ge,” was a woman because of the shape of the hip bone, Fred Hawker, head of research at the Vasa Museum, said in a statement.

Anna Maria Forsberg, a historian from the Vasa Museum, specified that women were not part of the crews of the Swedish fleet in the 17th century, but could be on board as guests. Sailors were allowed to take their wives with them on board unless the ship was going to battle or on a long voyage.

“We know from written sources that about 30 people died that day,” Forsberg says, adding: “So it is likely that she was a sailor’s wife who wanted to come with him on the maiden voyage of this new, impressive ship “. She also said that the exact number of people on board that day is not known, “but we estimate that there were about 150 people, with the assumption that another 300 soldiers were to be taken on board further in the archipelago.” .

Since 2004, the Vasa Museum has collaborated with Uppsala University’s Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology, which has been examining all the skeletons to learn as much as possible about the different people on the doomed ship. “Extracting DNA from bones that have been on the seabed for 333 years is very difficult, but not impossible,” says Marie Allen, professor of forensic genetics at Uppsala University. “Put simply, we found no Y-chromosomes in the ‘Ge’ genome, but we couldn’t be completely sure and wanted the results to be confirmed,” she explained.

So the Swedes turned to the Delaware-based DNA Identification Laboratory for the US Armed Forces. “Thanks to the forensic medical expertise in a new test, we were able to confirm that the individual ‘Ge’ was a woman,” explained Alain.

The Vasa, which was due to head to a naval base near Stockholm to wait for troops to board, is believed to have sunk because it had no ballast to counteract its heavy guns.