A team of European scientists, led by French archaeologist François Desset, has managed to decipher one of the great mysteries: linear Elamite script – a little-known writing system used in present-day Iran, writes Smithsonian Magazine.

The claim is hotly disputed by the researchers’ colleagues, but if true, then it could shed light on a little-known society that flourished between ancient Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley at the dawn of civilization. An analysis recently published in the journal Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie may also rewrite the evolution of writing itself. To decipher the reading of the characters that make up the linear Elamite script, experts used recently studied inscriptions from a set of ancient silver vases. “This is one of the great archaeological discoveries of recent decades. It is based on the identification and phonetic reading of the kings’ names,” said archaeologist Massimo Vidale of the University of Padua.

In 2015 Desset gained access to a private London collection of unusual silver vases with many inscriptions in both cuneiform and linear Elamite script. They were excavated in the 1920s and sold to Western traders, so their provenance and authenticity have been questioned. But analysis of the vessels found them to be ancient rather than modern forgeries. As for their origin, Desset believes they were in a royal cemetery hundreds of kilometers southeast of Susa, dated to around 2000 BC. – right around the time when the linear Elamite script was in use. According to the study, the silver vases represent the oldest and most complete examples of Elamite royal inscriptions in cuneiform. They belonged to different rulers of two dynasties. Stone with linear Elamite inscriptions from the Louvre collection.

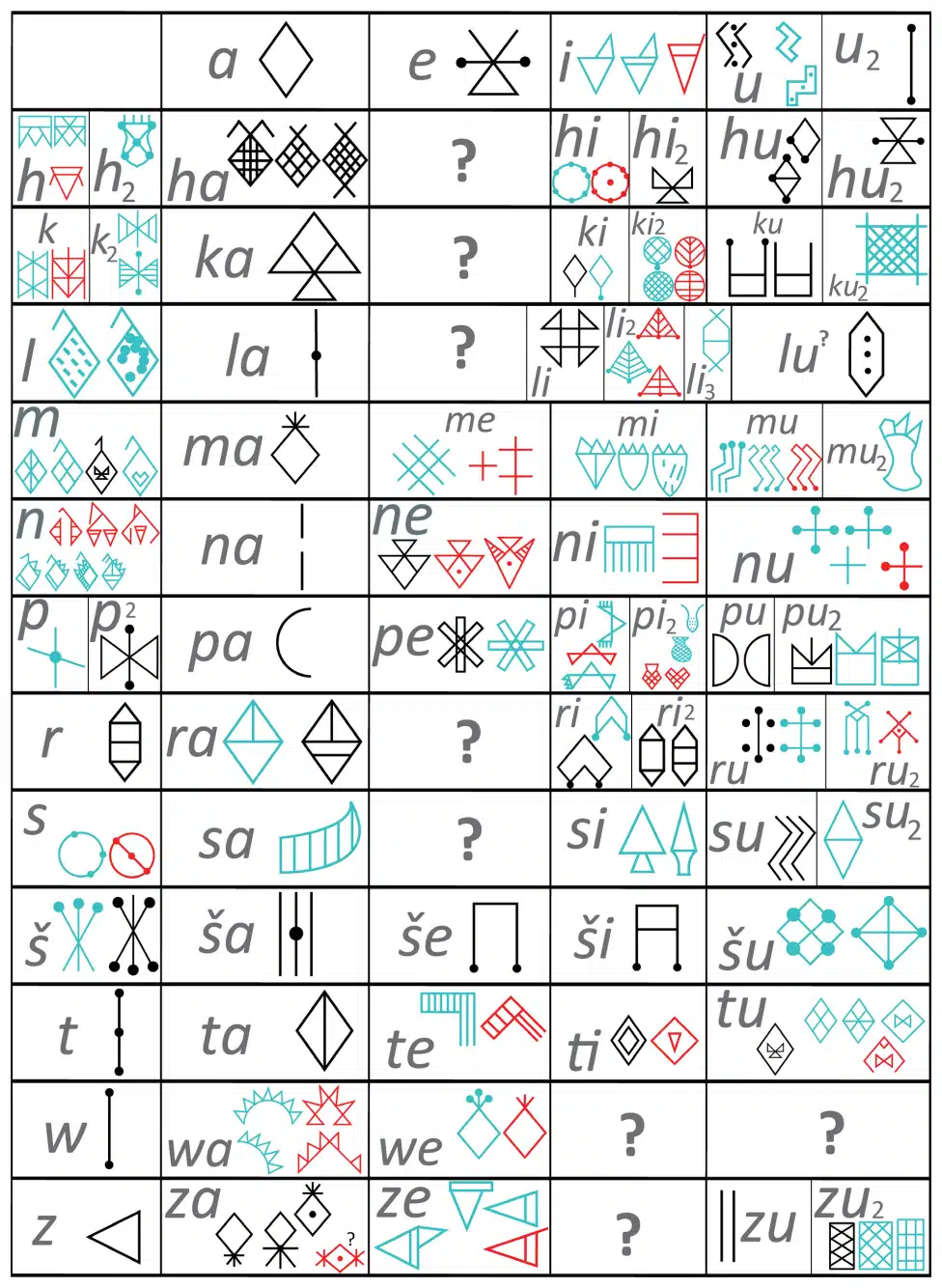

According to Desset, the juxtaposition of the inscriptions on the vessels was very useful in deciphering the linear Elamite script. Some names written in cuneiform can now be compared to symbols in the linear Elamite script, including the names of famous Elamite kings such as Shilhaha. By following the repeated signs, Desset was able to understand the meaning of the letter, consisting of a set of geometric figures. He also translated verbs like “give” and “make”. After subsequent analysis, Desset and his team claimed to be able to read 72 characters. “Although complete decipherment is not yet possible mainly due to the limited number of inscriptions, we are on the right track,” the authors of the study conclude. The hard work of translating individual texts continues. Part of the problem is that the Elamite language, which has been spoken in the region for more than 3,000 years, has no known cognates, making it difficult to determine what sounds the signs might represent.

The speakers of Elamite inhabited southern and southwestern Iran – Khuzestan, as in ancient Persian the name of Elam was Hujiyā, and Fars (as it is possible that it was also spread in other areas of the Iranian plateau before the 3rd millennium BC).

In the III millennium BC, a number of Elamite city-states are known from Sumero-Akkadian sources: Shushen (Shushun, Susa), Anshan (Anchan, today Tepe-Malyan near Shiraz in Fars), Simashki, Adamdun and others.

In the II millennium BC an important constituent of Elam were Shushen and Anchan. After the accession of Elam to the Achaemenid Empire in the middle of the 6th century BC, the Elamite language maintained its leading position for another two centuries, gradually giving way to Farsi.

Photo: Grid of the 72 deciphered alpha-syllabic signs on which the transliteration system of Linear Elamite is based. The most common graphic variants are shown for each sign. Blue signs are attested in southwestern Iran, red ones in southeastern Iran. Black signs are common to both areas. F. Desset