We have all heard the name Howard Carter and know that he is the discoverer of the famous tomb of Tutankhamun in Egypt. However, history knows no less colorful ladies who left an important scientific legacy in Egyptology. I personally have a special sentiment and interest in two of them, with whom I feel connected in a special way.

We have all heard the name Howard Carter and know that he is the discoverer of the famous tomb of Tutankhamun in Egypt. However, history knows no less colorful ladies who left an important scientific legacy in Egyptology. I personally have a special sentiment and interest in two of them, with whom I feel connected in a special way.

Natasha Rambova

she is like a heroine from a movie. Her birth name was Winifred Kimball Shawhennessy. In the 1920s, she was a student of the Russian ballet master and choreographer Teodor Kozlov, and in his honor, when she was 17, she adopted the artistic pseudonym Natasha Rambova, which gradually became her official name. Later, she became one of the most extravagant designers of costumes for theater productions and film productions, and created her own fashion line. Her name is constantly mixed up in love affairs with both men and women.

They say that her mentor Teodor Kozlov and the actress and film producer Alla Nazimova, with whom they created the classic “Salome” in 1922, were also madly in love with her. Natasha Rambova played many roles in Hollywood, created costumes that are emblematic of the spirit of the time. She also went down in history with her stormy two-year marriage, followed by an equally stormy divorce from Hollywood’s sex symbol at the time, Rudolph Valentino. Spicy, passionate and uncontrollable, Rambova is fascinated by all forms of art, but also by esotericism and spiritualism, and more than once declares to the sweet and melodramatic

Valentino that it is completely impossible for her to stay at home, look after children and set the table for afternoon tea. A few years after her divorce from Valentino in 1925, she married the aristocrat Alvaro de Urzaiz, and in 1936 she visited Egypt for the first time – the country that enchanted her forever and with which she would connect her life. He is then 39 years old.

Natasha spends nearly a month in Luxor. It was there that she met Howard Carter – a fateful meeting, because from that moment she decided that she would devote the rest of her life, all her means, energy, strength and emotions to the science of Egyptology. At that time he wrote in his personal diary: “I felt as if at last, after a long journey and wandering, I had returned home. The first days I was in Thebes, I couldn’t stop my tears, they just flowed from my eyes. But no!… these weren’t tears of sadness, but some kind of emotional release, some kind of impact from the past – a return to yourself and to the place you’ve loved for too long and you’re finally back, where it’s always been. your heart I’m home, I’m finally home!!!’

Natasha Rambova’s research and contribution to the development of Egyptology is truly remarkable. He began collecting and studying various religious texts, until one afternoon, looking for information in the Cairo library, he met the director of the Institute at the time, the Russian-born Egyptologist Alexander Piankov. This acquaintance would lead to some of the most serious research and the publication of valuable books related to the sacred religious texts of Ancient Egypt – the pyramid texts from the pyramid of King Unas of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt at Saqqara. Rambova took up research and editorial work and actively helped Piankov in his studies. Finds solid funding from foundations, helps field research in Luxor. The team obtained permission to photograph and study the inscriptions from the golden shrines that surround the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun in his tomb in the Valley. He worked as an editor on the first three volumes of the series “Egyptian religious texts” by Alexander Piankov and continued to deal with Egyptology until his last breath.

Nina McPherson Davis

She is the wife of another very talented and famous Egyptologist – Norman de Garris Davis. A true lady, a talented artist, copyist and Egyptologist, she is also known for her impeccable personal style – her long dark hair is always braided and smells of jasmine, her dress is unfailingly elegant and she always welcomes guests for afternoon tea at her house in Kurna, on The West Bank of Luxor, with fine china cups on a white linen tablecloth.

A fateful trip in 1906 to Alexandria linked her life to Egyptology. Then Nina was 25 years old and with a group of friends toured the sights of Ancient Egypt. Over a cup of tea, she meets Norman de Garris Davies, who is 16 years older than her. By this time, Norman was already an established Egyptologist, clearly stating his serious work and dedication to science. Behind him was work as an Egyptologist and copyist, and together with Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie worked at Dendera (1897-1898).

He then headed the Egypt Exploration Fund mission, resulting in 11 volumes of copies of tombs from Saqqara, Amarna, Sheikh Said and Deir el-Gebrawi. Between 1905 and 1907 he worked with George Reisner on the Giza Plateau, as well as with James Henry Breasted, describing and studying the monuments in Nubia. Love between the two ignited at first sight, and upon returning from her trip, Nina was already engaged to Norman, and a year later, in 1907, they were married in London. In the same year, Norman headed the epigraphic mission to Egypt of major ancient Egyptian necropolises. He and his wife, Nina, settled in Luxor, where Norman began his work at Sheikh ab del-Qurna. Almost their entire life together was spent there studying the texts and images from the tombs of several major ancient Egyptian necropolises. This will become their life’s work.

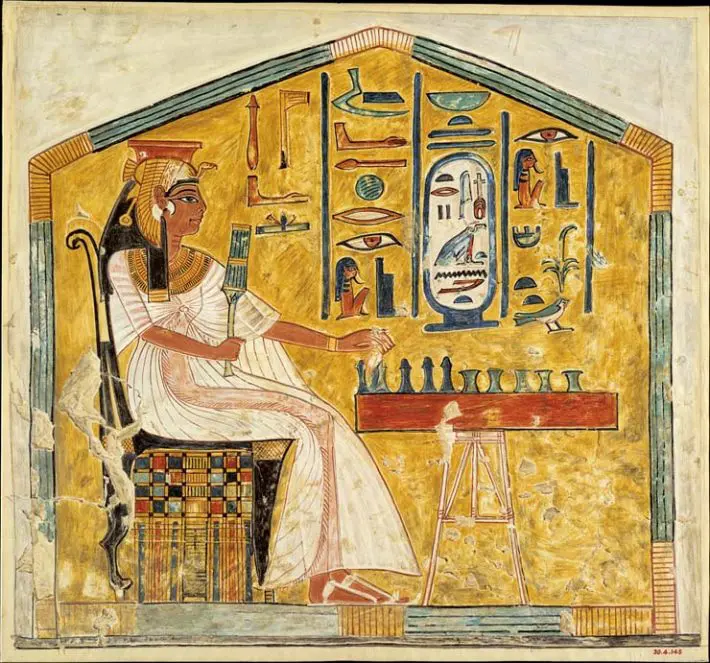

From 1913, Nina began working as a copyist for the Metropolitan Mission, just like her husband. This job requires extreme precision, an accurate eye and a talented hand. It is often dark and uncomfortable to work in the tombs. There is a lack of natural light in which to see the true colors. Texts and reliefs are destroyed, parts are missing, images are covered with layers of dust and dirt. Nina started using mirrors in her work to provide more light in the rooms.

Together with Norman, they began to use a new technique in their repaintings – instead of watercolor paints, they used tempera paints, with which they gave volume and density to the images. Nina mastered the technique, style and form of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics and imagery to such an extent that her renderings can still easily fool even the professional eye today. They live in a small house in Luxor, where in the evening they like to listen to music on their old gramophone, drink tea, and after dinner continue to work until the early hours of the next day.

Sir Alan Gardiner, one of the most famous British Egyptologists, was impressed by Nina’s talent and managed to organize several solo exhibitions of her in London and Oxford, and Rockefeller himself was included as a donor. With his help, two volumes of her works were published.

For the first edition of his Egyptian grammar, Sir Alan Gardiner asked Nina and Norman to produce a hieroglyphic character pool. They do, and in fact the grammar that all Egyptologists use today is based on the hieroglyphs written by Nina and Norman de Garris Davies.

In 1939, because of the complicated political situation immediately before the Second World War, the two left their house in Kurna and returned to England. Half of their belongings remain in Egypt, clearly indicating their intention to return and continue their work. However, on November 5, 1941, Norman died in his sleep of heart failure. Left alone, Nina never returned to Egypt and devoted her entire life to arranging, editing and publishing her husband’s unfinished works.