Written by archimandrite assoc. prof. Pavel Stefanov, Shumen University “Bishop Konstantin Preslavski” – Bulgaria

The sight of Jerusalem bathed in a dazzling spiritual light is exciting and unique. Situated among higher mountains on the banks of a deep gorge, the city radiates a constant imperishable glow. Even if it had no particular historical significance, it would still arouse strong feelings with its unusual appearance. Seen from the peaks of Skopos and Eleon, the horizon is littered with medieval fortifications and towers, gilded domes, battlements, crumbling remains from Roman and Arab times. Around it are valleys and slopes, transformed into spacious, green lawns that change even the properties of light. The view is fascinating.

According to the traditions of King David, he is called Jebus. In Hebrew, Yerushalayim means “city of peace” (this etymology is not quite specified – p. r.), which is a paradox, because in its thousand-year history it has known very few periods of peace. In Arabic, its name is al-Quds, which means “holy”. It is an ancient Middle Eastern city on the watershed between the Mediterranean and the Dead Sea at an altitude of 650-840 m. It represents an incredible mixture of monuments of history, culture and peoples with a huge amount of sights. From ancient times, this small provincial city was called the “navel” or “center” of the world because of its exceptional religious significance (so it is also called in the prophet Ezekiel 5:5 – b. r). [i] At different times, Jerusalem was a possession of the Kingdom of Judea, the State of Alexander the Great, Seleucid Syria, the Roman Empire, Byzantium, the Arab Caliphate, the Crusaders, the Ayyubid State, the Tatar-Mongols, the Mamluks, the Ottoman Empire, and the British Empire.[ii]

The age of Jerusalem exceeds 3500 years.[1] Archaeological research of this city, which occupies an exceptional place in the world’s spiritual history, began in 1864 and continues to this day.[2] The name Shalem (Salem) was first mentioned in 2300 BC. in the documents of Ebla (Syria) and in the inscriptions of the XII Egyptian dynasty. According to one version, it is a probable predecessor of Jerusalem.[3] In the 19th century BC mention is made of Melchizedek, king of Salem. According to the Bible, he met Abraham and the king of Sodom after a victorious battle and presented him with bread and wine, taking a tithe of them (Gen. 14:18-20). In the New Testament epistle to the Hebrews (5:6, 10; 6:20; 7:1, 10-11, 15, 17, 21) St. Apostle Paul proves the priestly dignity of Jesus Christ in the order of Melchizedek.

In the XIV century BC. during excavations by the Franciscan Fathers around the “Dominus Flevit” (“Lament of the Lord”) chapel, ceramic and earthenware items dating back to the 16th century BC, as well as an ornament in the form of a scarab beetle from Egypt, were discovered. A chance find, a set of cuneiform tablets from Tell el-Amarna in Upper Egypt (ca. 1350 BC), sheds light on the royal archive of Amenhotep III and his son Akhenaten. Among some 400 notices on clay of princes and chiefs in Palestine, Phoenicia and southern Syria are eight by one Abdu Heba, ruler of Jerusalem and vassal of Egypt. In his anxious letters to the pharaoh, Abdu Heba begs for reinforcements, which he does not receive, and loses the pharaoh’s land “from habiru”. Who were these “habiru” tribes? The connection between them and the ancient Jews remains a matter of conjecture.

The history of Jerusalem begins with the proto-urban period, to which several burials refer. With its first settlement in the Late Bronze Age, it became a city of the Jebusites, a Canaanite tribe. It is located on Mount Ophel (on the southeastern outskirts of present-day Jerusalem). “But the sons of Judah could not drive out the Jebusites, residents of Jerusalem, and therefore the Jebusites live with the sons of Judah in Jerusalem even to this day” (Isa. Nav. 15:63).[4]

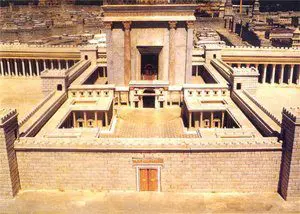

From 922 to 586 BC. Jerusalem is the capital of the Jewish kingdom. The city was captured by the Jews, led by King David (in the last decade, the opinion prevailed that the city was not captured by force – b. r.). David found an ancient sanctuary existing here and renamed the city Zion.[5] He built a palace (2 Kings 5:11), but its foundations have not yet been discovered. The king renovated the city and the walls, including the so-called Milo (1 Chronicles 11:8). The meaning of this term is unclear, but it is thought to refer to the terraces and foundations of the acropolis. Solomon turns Jerusalem into a lavish capital. He doubled the size of the city and built a temple complex on Mount Moriah (2 Chronicles 3:1).[6] The pious king Hezekiah (727-698) rebuilt the fortress walls and dug a water supply tunnel.[7] The Assyrian king Sennacherib besieged Jerusalem in 701, but an angel of the Lord killed 185,000 of his soldiers and the invaders retreated.

In 598 BC. the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar besieges Jerusalem, which falls, and the Judean king Jeconiah is taken captive to Babylon. Zedekiah was placed on the throne as a vassal. He rebelled, hoping for help from Egypt. In 587, the Babylonian army returned and destroyed Jerusalem. Almost all the inhabitants were taken as captives to Babylon. In 539 BC the Persian king Cyrus the Great defeated the Babylonians and issued a decree allowing the Jews to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the temple.[8]

The year is 332 BC. The inhabitants of Jerusalem surrendered without resistance to Alexander the Great, who confirmed the privileges given to the city by the Persian rulers.[9]

Under the leadership of the Maccabee brothers, a revolt of the Jews broke out, which lasted from 167 to 164 BC. The Syrian occupiers of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who were imposing paganism, were driven out.[10]

Roman troops under the leadership of Pompey captured Jerusalem in 63 BC. The city became the administrative center of the Roman protectorate of Judea.[11] The modern plan of Jerusalem dates from the time of Herod the Great (37-34 BC).[12] This satrap is the greatest builder in the history of the city. He rebuilt the Hasmonean walls and added three large towers, built a palace-administrative complex on the western hill, later called the “praetorium”, and rebuilt the temple. Diaspora Jews long for the city, led by eminent intellectuals such as Philo of Alexandria.[13]

Roman oppression fueled the secret liberation movement of the Zealots. Christ’s apostle Judas Iscariot probably belongs to them.[14] In 66-70, the Jews led a revolt against the Romans. After a long siege, Jerusalem falls. The failed uprising goes down in history as the Jewish War. Despite the order of the Roman general Titus to preserve the temple, it was burned and destroyed on 9 Aug 70.[15] Later, by order of the emperor Hadrian, the construction of a city called Elia Capitolina in honor of the emperor (Elius Hadrian) and the Capitoline triad (Jupiter, Juno and Minerva) began on the ruins of Jerusalem. The city was built on the model of a Roman military camp – a square in which the streets intersect at right angles. A sanctuary of Jupiter was built on the site of the Jewish temple.

Outraged by the imposition of the pagan cult, the Jews raised a second revolt against the Roman conquerors. From 131 to 135, Jerusalem was in the hands of the Jewish rebels of Shimon bar Kochba, who even minted his own coins. But in 135 the Roman troops recaptured the city. Emperor Hadrian issued a decree banning all circumcised persons from entering the city. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, the Byzantine period began and the city gradually took on a Christian appearance.[16]

On the site of Golgotha, the Romans erected a temple to Aphrodite. In 326, St. Helena and Bishop Macarius led the construction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Millions of pilgrims from all over the world began to flock here over the centuries.

In 1894, a famous mosaic depicting St. George was discovered in the Orthodox Church of St. George in Madaba (now Jordan). Earth and Jerusalem. It dates from the 6th century and today measures 16 x 5 m. The largest and most detailed image in the center of the work is of Jerusalem and its landmarks.[17]

In 614, the city was captured and looted by the Persian Shah Khozroi, and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was burned. After 24 years, St. Patriarch Sophronius opened the city’s doors to a new conqueror – the Arab caliph Omar ibn al-Khattab, and Jerusalem gradually began to acquire a Muslim appearance. A little later, Mu’af I, founder of the Umayyad dynasty, was proclaimed caliph in Jerusalem. A mosque was built on the site of the destroyed Jewish temple, which for Muslims is the third holiest after those in Mecca and Medina.

In 1009, the insane caliph al-Hakim ordered the complete destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This sacrilege causes a wave of protest in the West and prepares the age of the Crusades. In 1099, the participants in the first campaign under the leadership of Count Gottfried of Boulogne captured Jerusalem, massacred all Muslims and Jews and turned the city into the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem headed by King Baldwin I. In 1187, after a long siege, the troops of the Egyptian Sultan Salah-at -din (Saladin, 1138-1193) conquered Jerusalem. All the churches in the city except the Ascension Church were converted into mosques. [18]

But Western Christians did not despair and in 1189-1192 organized the Second Crusade under the leadership of the English king Richard the Lionheart. The city again falls into the hands of the Crusaders. In 1229, Friedrich II Hohenstaufen became king of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, who managed to temporarily restore the power of the Crusaders in Jerusalem by taking advantage of the contradictions between the Muslim states. However, in 1244, the Mongol-Tatars conquered the city. In 1247, Jerusalem was captured by an Egyptian sultan of the Ayyubid dynasty. The Mamluks came to power – bodyguards of the Egyptian sultans, whose army was recruited from slaves of Turkic and Caucasian (mainly Circassian) origin. In 1517, the army of the Ottoman Empire, after a victory in Syria over the Mamluks, conquered the land of Eretz-Israel (the territory of Palestine) without bloodshed.

During World War I, Britain established control over Palestine .[19] From 1920 to 1947, Jerusalem was the administrative center of the British mandated territory of Palestine. During this period the Jewish population increased by 1/3 mainly due to migration from Europe. UN General Assembly Resolution No. 181 of November 29, 1947, known as the Resolution on the Partition of Palestine, assumed that the international community would take control of the future of Jerusalem after the end of the British Mandate (May 15, 1948). ).[20] In 1950, Israel declared Jerusalem as its capital and all branches of the Israeli government were located there, although this decision was not accepted by the world community. The eastern part of the city became part of Jordan. [21]

After its victory in the Six-Day War in 1967, Israel gained control of the entire territory of the city, legally separated East Jerusalem from the West Bank and declared its sovereignty over Jerusalem. With a special law of July 30, 1980, Israel declared Jerusalem to be its single and indivisible capital. All state and government offices of Israel are located in Jerusalem. [22] The UN and all its members do not recognize the unilateral annexation of East Jerusalem. Almost all countries have their embassies in the Tel Aviv area, with the exception of several Latin American countries, whose embassies are located in the Jerusalem suburb of Mevaseret-Zion. As early as 2000, the US Congress passed a decision to move the embassy to Jerusalem, but the American government constantly postponed the implementation of this decision. In 2006, the Latin American embassies moved to Tel Aviv, and now there are no foreign embassies in Jerusalem. East Jerusalem houses the consulates of the United States and some other countries that have contact with the Palestinian Authority.

The status of Jerusalem remains a hotly contested topic. Both Israel and the Palestinian Authority officially claim Jerusalem as their capital and do not recognize that right to any other country, although Israeli sovereignty over part of the city is not recognized by the UN or most countries, and the Palestinian Authority’s authorities have never they were not in Jerusalem. The Arabs even completely deny the Jewish period of Jerusalem’s history, thereby disputing the Bible, accepted as revelation in their Koran. After the victory of the Islamic revolution in Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini established a new holiday on October 5 – the day of al-Quds (Jerusalem). Every year on this date, Muslims pray for the city to be freed from the Israeli military presence.[23]

According to the latest figures, the inhabitants of Jerusalem number 763,800, while in 1948 they were only 84,000. There are 96 Christian, 43 Islamic and 36 Jewish shrines located on the territory of the old city, which covers only 1 square km. He is associated with peace through his name. It is a medium-sized, provincial, in many ways modest and yet irresistibly attractive city that inspires awe and wonder. Two world religions were founded in Jerusalem, and the third, Islam, adopted its various traditions in its creed. But instead of being like its name “city of peace”, Jerusalem turns out to be an arena of confrontation.

The violence continues as acts in an endless ancient drama, but in which there is no catharsis. From the same walls climbed by the Romans in AD 70 and the Crusaders in 1099, Palestinian youths armed like David with slings pelt passing armored police cars with stones. Helicopters circle above, dropping tear gas canisters. Nearby, in the narrow streets, the sounds of the three faiths that hold the city sacred rise incessantly – the voice of the muezzin calling the Muslim faithful to prayer; the ringing of church bells; the chant of Jews praying at the Western Wall – the only preserved part of the ancient Jewish temple.

Some call Jerusalem a “necrocracy” – the only city where the deciding vote is given to the dead. Everywhere here one feels the heavy burden of the past weighing on the present. For Jews, it is always the capital of memory. For Muslims it is al-Quds, ie. The sanctuary, from the emergence of Islam in the 7th century to today. For Christians, it is the epicenter of their faith, associated with the preaching, death and resurrection of the God-man.[24]

Jerusalem is a city where the spirit of history is daily relentlessly and superstitiously invoked by rival countries. Jerusalem is the embodiment of the influence of memory on the minds of men. It is a city of monuments that have their own language. They awaken mutually contradictory memories and build its image as a city dear to more than one people, sacred to more than one faith. In Jerusalem, religion mixes with politics. He lives too deeply engrossed in the fascination of powerful religious beliefs and religions.[25] The reverence and fanaticism of the religions and nationalities coexisting here interact. There was never a single religious truth in Jerusalem. There have always been many truths and mutually contradictory images of the city. These images reflect or distort each other and the past flows into the present.

In our time, men have set foot on the moon in search of new promised lands and new Jerusalems, but so far the old Jerusalem has not yet been replaced. He retains an extraordinary hold over the imagination, holding for three faiths at once near and far a fear and hope of an Apocalypse expressed in entirely interchangeable phrases.[26] Here, the religious struggle to conquer territories is an ancient form of worship. Nationalism and religion have always been intertwined in Jerusalem, where the idea of a promised land and a chosen people was first revealed to the Jews 3,000 years ago.

The Jerusalem scribes and prophets challenged the prevailing ancient notion that history necessarily moves in circles, repeating itself over and over again. They express the overarching hope for irreversible progress toward a better and more valuable life. Varieties of the Pentateuch and the books of Joshua, Samuel, and Kings circulated in Jerusalem as oral traditions in the early 7th or 9th century BC. Archaeological and epigraphic evidence repeatedly confirms with remarkable accuracy the factual details of the biblical sources. Here King David composed the poems of the Psalms, and Solomon built the temple and enjoyed his hundreds of wives. Here Isaiah cries out in the wilderness, and Jesus wears the crown of thorns and is crucified with the robbers. Christians gathered after His death in this city and in the name of hope conquered the Roman Empire and the entire Mediterranean world. Here, according to Islamic legend, Muhammad comes on a mysterious winged white horse and ascends to heaven on a ladder of light. Since the 12th century, Jews have been praying at the Western Wall three times a day, so that they can “return by mercy to Your city of Jerusalem and live in it, as You promised.”

Four thousand years of history, countless wars and extremely strong earthquakes, some of which caused the complete destruction of buildings and walls, have left their mark on the topography of the city. It has experienced 20 devastating sieges, two periods of complete desolation, 18 restorations and at least 11 conversions from one religion to another. Jerusalem remains holy to Jews, Christians and Muslims, to all people of the world. “Ask for peace for Jerusalem” (Ps. 121:6)!

Notes:

[i] Wolf, B. Jerusalem und Rom: Mitte, Nabel – Zentrum, Haupt. Die Metaphern «Umbilicus mundi» und «Caput mundi» in den Weltbildern der Antike und des Abendlands bis in die Zeit der Ebstorfer Weltkarte. Bern u.a., 2010.

[ii] Encyclopedic dictionary. Christianity. T. I. M. 1997, p. 586. Cf. Otto, E. Das antike Jerusalem. Archaeologie und Geschichte. München, 2008 (Beck’sche Reihe, 2418).

[1] Elon, A. Jerusalem: City of Mirrors. London, 1996, p. 30.

[2] Whiting, C. Geographical Imaginations of the “Holy Land”: Biblical Topography and Archaeological Practice. – Nineteenth-Century Contexts, 29, 2007, Nos. 2 & 3, 237-250.

[3] Elon, A. Op. cit., p. 54.

[4] For the ancient history of the city, see Harold Mare, W. The Archeology of the Jerusalem Area. Grand Rapids (MI), 1987; Jerusalem in Ancient History and Tradition. Ed. by T. L. Thompson. London, 2004 (Copenhagen International Seminar).

[5] Cogan, M. David’s Jerusalem: Notes and Reflections. – In: Tehillah le-Moshe: Biblical and Judaic Studies in Honor of Moshe Greenberg. Edited by M. Cogan, B. L. Eichler, and J. H. Tigay. Winona Lake (IN), 1997.

[6] Goldhill, S. The Temple in Jerusalem. S., 2007.

[7] The book Jerusalem in Bible and Archeology: The First Temple Period is devoted to the biblical history of Jerusalem. Ed. by A.G. Vaughn and A.E. Killebrew. Atlanta (GA), 2003 (Symposium Series, 18)

[8] Encyclopedic dictionary. Christianity. T. I. M., 1997, 587. Cf. Ritmeyer, L. Jerusalem in the time of Nehemiah. Chicago, 2008.

[9] Ameling, W. Jerusalem als hellenistische Polis: 2 Makk 4, 9-12 und eine neue Inschrift. – Biblische Zeitschrift, 47, 2003, 117-122.

[10] Tromp, J. The Religious Significance of Jerusalem for Jews in the Greco-Roman Period. – In: À la recherche des villes saintes. Actes du colloque franco-néerlandais “Les Villes Saintes”. Ed. A. Le Boulluec. Turnhout, 2004 (Bibliothèque de l’École des hautes études. Sciences religieuses, 122), 51-61.

[11] Mirasto, I. Christ is Risen (In God’s Land during Holy Week). S., 1999, p. 9.

[12] Julia Wilker, Fuer Rom und Jerusalem. Die herodianische Dynastie im 1. Jahrhundert n.Chr. Frankfurt am Main, 2007 (Studien zur Alten Geschichte, 5)

[13] Pearce, S. Jerusalem as “Mother-City” in the writings of Philo of Alexandria. – In: Negotiating Diaspora: Jewish Strategies in the Roman Empire. Ed. by J.M.G. Barclay. London and New York, 2004, 19-37. (Library of Second Temple Studies, 45).

[14] Hengel, M. The Zealots: Investigations into the Jewish Freedom Movement in tho Period from Herod I until 70 AD. London, 1989.

[15] Rives, J.B. Flavian Religious Policy and the Destruction of the Jerusalem Temple. – In: Flavius Josephus and Flavian Rome. Eds. J. Edmondson, S. Mason, and J. Rives. Oxford, 2005, 145-166.

[16] Belayche, N. Déclin ou reconstruction? La Palaestina romaine après la révolte de ‘Bar Kokhba’. – Revue des études juives, 163, 2004, 25-48. Cf. Colbi, P. A Short History of Christianity in the Holy Land. Jerusalem, 1965; Wilken, R. The Land Called Holy: Palestine in Christian History and Thought. New York, 1992.

[17] Damyanova, E. Jerusalem as the topographical and spiritual center of the Madaba mosaic. – In: Theological Reflections. Collection of materials. S., 2005, 29-33.

[18] Shamdor, A. Saladin. A noble hero of Islam. St. Petersburg, 2004. Cf. L’Orient au temps des croisades. Textes arabes presented et traduit par A.-M. Eddé et F. Micheau. Paris, 2002.

[19] Grainger, J. The Battle for Palestine, 1917. Woodbridge, 2006.

[20] The Christian Heritage in the Holy Land. Ed. By A. O’Mahony with G. Gunner and K. Hintlian. London, 1995, p. 18.

[21] Keay, J. Sowing the Wind: The Seeds of Conflict in the Middle East. New York, 2003.

[22] Tessler, M. History of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Bloomington (IN), 1994. Cf. Kailani, W. Reinventing Jerusalem: Israeli’s Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter After 1967. – Middle Eastern Studies, 44, 2008, No. 4, 633-637.

[23] Emelyanov, V. What to do with the problem of al-Quds – Jerusalem? In Moscow, they celebrated a memorial date established 27 years ago by Imam Khomeini. – https://web.archive.org/web/20071011224101/https://portal-credo.ru:80/site/?act=news&id=57418&cf=, October 8, 2007.

[24] The Christian Heritage.., p. 39.

[25] Kalian, M., S. Catinari, U. Heresco-Levi, E. Witztum. “Spiritual Starvation” in a Holy Space: a Form of “Jerusalem Syndrome”. – Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 11, 2008, No. 2, 161-172.

[26] Elon, A. Op. cit., p. 71.

Short address of this publication: https://dveri.bg/uwx