Learn more about the troubling theory of human improvement

The term “eugenics” refers to a set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the perceived genetic quality of the human population.

Although most often associated with the Nazi regime of the 1930s and 1940s, the history of eugenics is far more comprehensive than that, both in time and geographically.

The basic idea of eugenics is that the human race can be genetically improved by excluding those groups that are considered lower and encouraging those groups that are considered higher.

While the term was most commonly used under the Nazi regime of the 1930s and 1940s, the concept of eugenics actually dates far back.

Browse our gallery and find out more about eugenics:

Ancient Greece: There is evidence of attempts to control human populations dating back to the ancient Greeks. Around 400 BC, Plato actually proposed selective breeding in humans.

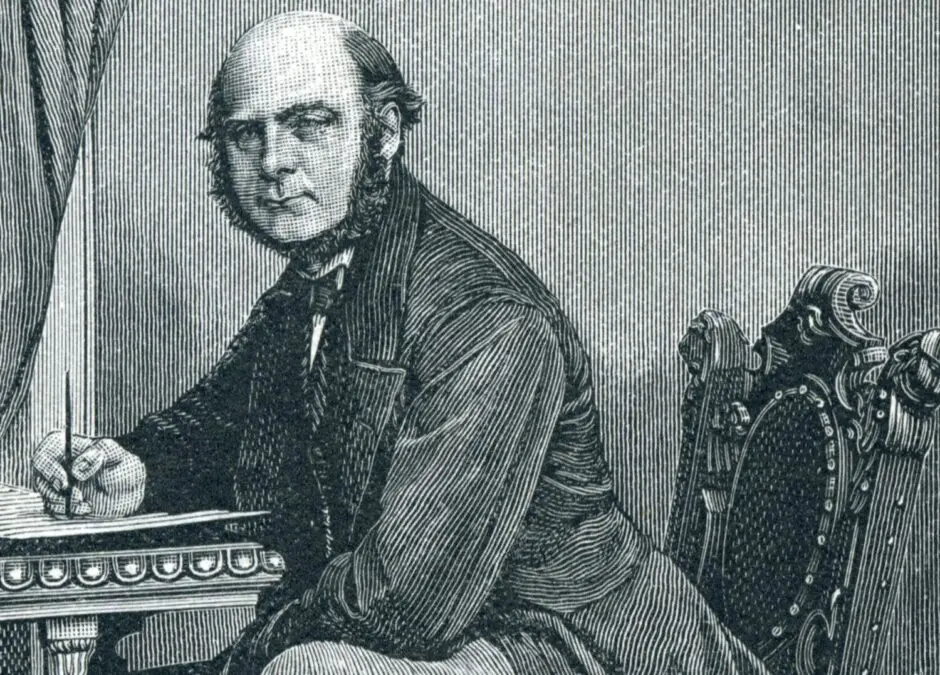

Modern eugenics: The modern history of eugenics began in the late 19th century, when the discovery of evolution and genetics sparked a new scientific movement dedicated to the cause. The movement first appeared in the United Kingdom, where it was named by British scientist Francis Galton. The word “eugenics” comes from the Greek “eugenes”, which means “well born”.

From the United Kingdom, the movement spread to many countries around the world, including the United States, Canada, Australia and many European countries. With the spread of the movement, people began to wonder which genetic traits were desirable and which were not. The problem was that the desired genetic traits were largely determined by the prejudices that existed in the country at the time. Whole groups of people, including immigrants and people with disabilities, were considered “unfit” for reproduction based on their genetic traits.

Many countries have taken steps to control reproduction among “undesirable groups”, such as restricting immigration and banning interracial alliances. Perhaps the most horrific example of eugenics in action is the Nazi regime in Germany, which systematically eliminated millions of Jews and other minorities. The enormous scale and brutality of the Nazi regime made it an extraordinary event in the history of eugenics.

However, Nazi eugenic policy did not differ from the policies pursued by other governments around the world in the mid-20th century. Many countries have introduced formal eugenics policies, of which sterilization has often been a key element. Sweden, Canada and Japan, for example, have forcibly sterilized thousands of people. Sterilization of individuals with “undesirable” characteristics was particularly common in the United States. Between 1907 and 1979, more than 60,000 people in the United States were sterilized under eugenics policies, and 32 states passed laws to sterilize “mentally defective” individuals.

A person has often been defined as “mentally defective” based on superficial mental health diagnoses and intelligence tests. Moreover, the tests used to determine an individual’s mental capacity were often linguistically and culturally biased against the immigrant population. The situation in California, USA was particularly severe between 1920 and 1945 – many more Latin American women were sterilized than other women.

After the atrocities of World War II, many countries began to ban their eugenics policies, although some countries continued to use forced sterilization for decades. The countries that have slowly given up forced sterilization are Sweden and the United States, and laws in California were not repealed until 1979.

Although the general influence of eugenics has been blunted since the mid-20th century, many countries continue to carry out illegal forced sterilizations. In addition, since the 1980s and 1990s, there have been fears that eugenics may return with a vengeance thanks to new technologies. The development of assisted reproductive technology procedures, including cytoplasmic transfer, which was first performed in 1996, has raised concerns about a new, more powerful form of eugenics.

Illustration: Francis Galton