Scientists have discovered a fragment of an Elamite inscription as part of a project to classify and document objects in the warehouses of the Persepolis Museum in Iran. The inscription repeats an earlier Old Persian text. Clay tablets, written mostly in Elamite, are artifacts that have been studied for nearly a century. Many such tiles were discovered by an expedition of archaeologists from the University of Chicago in the 1930s during excavations of the ruins of Persepolis, an ancient Persian city located in southwestern Iran and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The artifacts went to the United States, but returned to Iran in 2019 as part of expanding contacts between scientists on both sides. Now Iranian archaeologist Soheli Delshad says he has found a fragment of Elamite on one of the tablets. The text largely follows the Old Persian inscription of the Achaemenid king Darius I on both sides of the entrance to the tomb at Nagsh-e Rostam, an ancient necropolis of Persian kings located two kilometers from Persepolis.

The Elamite language is an extinct language spoken by the inhabitants of the ancient state of Elam, which included the region from the Mesopotamian Plain to the Iranian mountains. The earliest objects found date from the third millennium BC, the so-called Elamite period. Then the rulers of the Achaemenid kingdom (550-330 BC) were buried here. The latest finds date from the period of the Sassanid Empire (221-656 AD). The inscription carved at the entrance to the tomb is one of the first Achaemenid inscriptions studied and published by Iranian scholars. The original text dates from the reign of Darius I (522-486 BC), while its Elamite copy refers to the period when the Achaemenid state was headed by Xerxes I (486-465 BC). f.). Military wells of the pharaohs were discovered in Egypt Today it is believed that the ancient Persian script is one of the most ancient. It is logical that the earlier inscription was made in Old Persian, and the later – in Elamite. But Xerxes I is the son of Darius I and succeeds him to the royal throne – that is, it does not take long for the language to change. Apparently this change happened earlier. At that time, the state of Elam itself did not exist for a long time: the Assyrian ruler Ashurbanipal was done with it. But the language is still used on an equal footing with Old Persian. Then, around the time of Darius’ reign, Elamite began to displace Old Persian – at least this state of affairs is reflected in the sources, these same clay tablets. Most of them are filled with Elamite inscriptions.

These records are basically the usual bureaucratic documentation: payrolls, orders, diplomatic correspondence. That is, the Elamite language was understandable to most of the inhabitants of the Achaemenid state. Some signs contain, for example, instructions for construction managers on the lower level of Persepolis. In other words, every worker spoke or read Elamite. Based on this, scholars suggest that the Elamite language, during the reign of Darius and then his son Xerxes, actually replaced ancient Persian from everyday use. But, judging by the inscription at the entrance to the tomb, the latter remains a sacred language, the language of rites and rituals. The clay tablets in question are divided into two groups according to the place of discovery and content. The first were found in the area of military fortifications in the northeastern part of Persepolis, hence their name – “fortifications of Persepolis”.

The find consists of more than 30,000 tablets, whole or fragmentary, of which 2,120 texts have already been read, and the rest remain unsolved. These documents are dated to 509-494 BC. Although they were all in Persepolis, many came from other parts of the empire, such as Susa. The second group of clay tablets was found in the treasury of Xerxes, which is why they are tentatively called “Plaques from the treasury of Persepolis.” They are dated to 492-458 BC. (that is, from the end of Darius’ reign to the accession to the throne of his grandson Artaxerxes I). A total of 753 tiles and fragments have been found, of which 128 have been deciphered so far. Many of the fragments are too worn or broken to form a coherent text. The tables in the first group include numerous records of transactions (mainly related to the distribution of food, herd management, provision of workers and travelers) on the outskirts of the empire.

The second group contains mainly texts relating to the life of Persepolis itself.

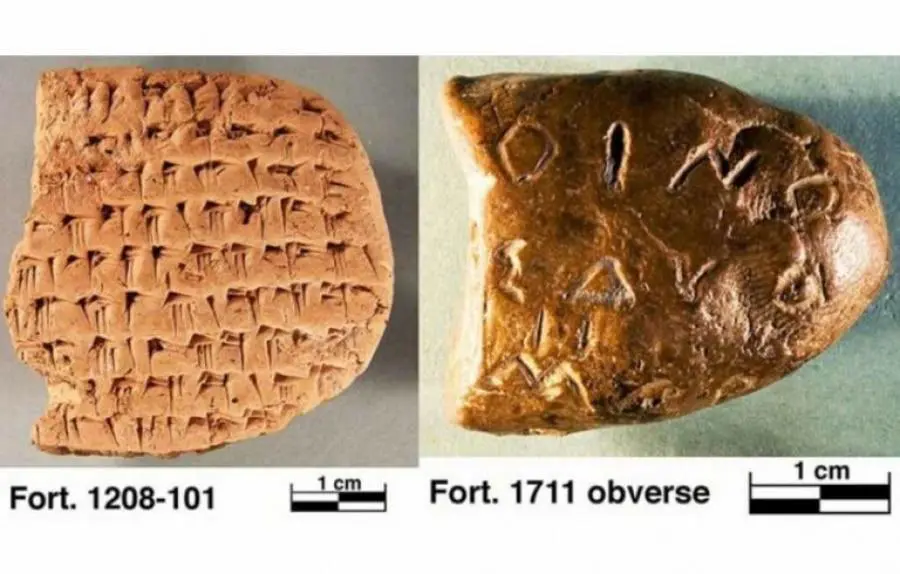

Photo: Comparison of Elamite cuneiform with Old Persian and Babylonian. Immanuel Giel / CC BY-SA 3.0