The pandemic – and government backing – have led to a dramatic increase in art tourism in China. The most popular route is a weekend visit to the Buddhist temples of the Tang Dynasty, 250 km from Beijing. Experts fear if they can withstand such an influx of visitors

Chinese tourists spent $ 254.6 billion abroad in 2019, according to the UN World Tourism Organization, a year before the pandemic. Given the fact that China is unlikely to open until 2022, today the Chinese have no choice but to switch to local attractions offered by domestic companies.

“Since July last year, we have had a lot of new people in our groups,” says Bai Yu, founder of Lishi Jiangtan Travel Company. At one time, he was so carried away by history that in 2015 he moved from the technology sector to the field of cultural tourism and is now organizing individual trips for small groups of 10 to 20 people. “There are more than 9 million travelers in China who are accustomed to overseas, and many of them are waiting for a similar themed product, an alternative to overseas tours that they are willing to pay for.”

Most of Bai Yu’s clients are over 35 years old, well-educated, well-to-do and travel alone rather than with their family. According to him, about 90% are women. These wealthy new customers want a quality product that they are willing to pay for. This year, tourists spent an average of 1,000 to 1,200 yuan ($ 155-185) per day, which is three times more than in 2015. So his company doubled the number of employees.

However, interest in China’s cultural treasures began to grow even before the pandemic interrupted international flights. In 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping declared “faith in the great culture of China” as a national political doctrine. In 2018, a number of government agencies for tourism and culture merged into the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

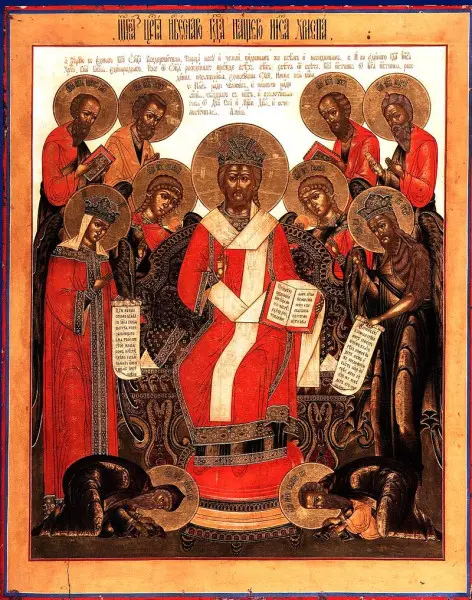

“You can miss the blue ocean (that is, a niche where there is no competition yet. – TANR) if you do not follow the presidential decree, especially when the government is providing generous support to the entire industry,” says Yang Jie, 15 years as a manager at McDonald’s, and founder of Jinxingji in 2017. In 2020, his team organized cultural tours for more than 5,000 travelers. The most popular itinerary is a weekend visit to the Tang Dynasty Buddhist temples on Mount Wutai in Shanxi province, about 250 km southwest of Beijing. Unlike natural attractions, according to Yang Jie, “cultural sites must be told so that tourists can fully appreciate their significance,” and this is where agencies like his come into play.

Until the covid is defeated and the likelihood of travel cancellations remains, the agencies are actively working on the Web in parallel. Nie Mengqiao, a partner at Yilü, notes that half of her company’s activities are related to Internet programs. They lecture on Buddhist statues, ancient architecture and Chinese heritage in Western museum collections. Experts from leading universities and research institutes are invited as lecturers, some also travel with groups. Depending on their qualifications, lecturers receive daily royalties ranging from 1,000 ($ 155) to 20,000 yuan ($ 3,100), and renowned scientists can earn up to 100,000 yuan ($ 15.5 thousand).

“Most of the specialists in cultural institutions graduated from prestigious universities, but they work for modest salaries. The money we pay them is just a recognition of their academic achievements, says Nie Mengqiao. “And we are offering more job opportunities to those who have recently graduated from college.”

The growth in the number of tourists inevitably raises concerns among experts: will the ancient monuments suffer from such an influx of people? According to a 2012 national survey, mainland China has more than 766,000 immovable cultural heritage properties, with only about 130,000 professionals servicing them. The lack of staff means that some properties are left unattended while others are closed to the public.

While it is the responsibility of the state to protect China’s cultural heritage sites, travel agency managers agree that they are responsible for raising awareness among tourists and making small donations for the maintenance of the monuments.

The Bai Yu firm operates under the patronage of government cultural organizations, gaining access to certain areas normally closed to the public at an additional cost. “We’re willing to pay for this privilege,” he says. “The money you give for visiting a cultural landmark is a direct recognition of its value and significance.”

Photo: Ling Tang. Forbidden City in Beijing (Gugong).