NASA’s newest Mars rover is beginning to study the floor of an ancient crater that once held a lake.

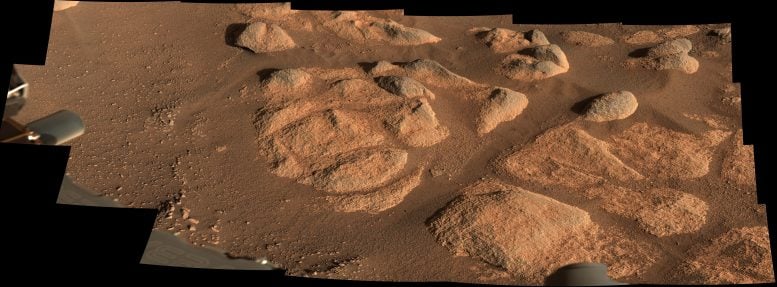

Mastcam-Z Views ‘Santa Cruz’ on Mars: NASA’s Perseverance Mars rover used its dual-camera Mastcam-Z imager to capture this image of “Santa Cruz,” a hill about 1.5 miles (2.5 kilometers) away from the rover, on April 29, 2021, the 68th Martian day, or sol, of the mission. The entire scene is inside of Mars’ Jezero Crater; the crater’s rim can be seen on the horizon line beyond the hill. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU/MSSS

NASA’s Perseverance rover has been busy serving as a communications base station for the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter and documenting the rotorcraft’s historic flights. But the rover has also been busy focusing its science instruments on rocks that lay on the floor of Jezero Crater.

What insights they turn up will help scientists create a timeline of when an ancient lake formed there, when it dried, and when sediment began piling up in the delta that formed in the crater long ago. Understanding this timeline should help date rock samples – to be collected later in the mission – that might preserve a record of ancient microbes.

Perseverance’s Mastcam-Z Images Intriguing Rocks: NASA’s Perseverance rover viewed these rocks with its Mastcam-Z imager on April 27, 2021. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU/MSSS

A camera called WATSON on the end of the rover’s robotic arm has taken detailed shots of the rocks. A pair of zoomable cameras that make up the Mastcam-Z imager on the rover’s “head” has also surveyed the terrain. And a laser instrument called SuperCam has zapped some of the rocks to detect their chemistry. These instruments and others allow scientists to learn more about Jezero Crater and to home in on areas they might like to study in greater depth.

One important question scientists want to answer: whether these rocks are sedimentary (like sandstone) or igneous (formed by volcanic activity). Each type of rock tells a different kind of story. Some sedimentary rocks – formed in the presence of water from rock and mineral fragments like sand, silt, and clay – are better suited to preserving biosignatures, or signs of past life. Igneous rocks, on the other hand, are more precise geological clocks that allow scientists to create an accurate timeline of how an area formed.

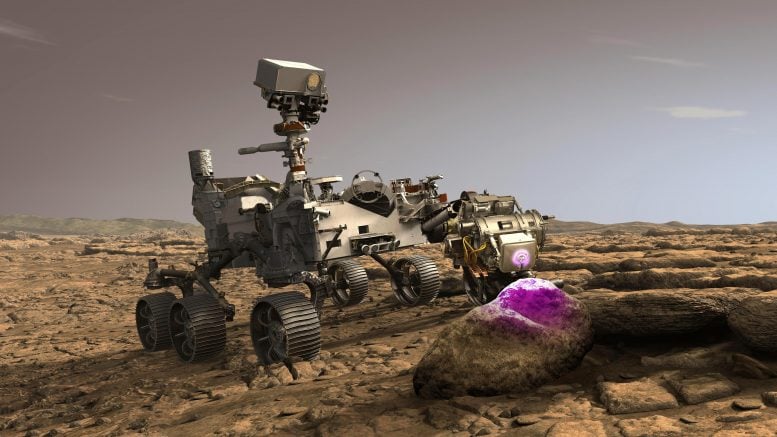

NASA’s Perseverance Mars rover used the WATSON camera on the end of its robotic arm to conduct a focus test on May 10, 2021, the 79th Martian day, or sol, of the mission. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

One complicating factor is that the rocks around Perseverance have been eroded by wind over time and covered with younger sand and dust. On Earth, a geologist might trudge into the field and break a rock sample open to get a better idea of its origins. “When you look inside a rock, that’s where you see the story,” said Ken Farley of Caltech, Perseverance’s project scientist.

While Perseverance doesn’t have a rock hammer, it does have other ways to peer past millennia’s worth of dust. When scientists find a particularly enticing spot, they can reach out with the rover’s arm and use an abrader to grind and flatten a rock’s surface, revealing its internal structure and composition. Once they’ve done that, the team gathers more detailed chemical and mineralogical information using arm instruments called PIXL (Planetary Instrument for X-ray Lithochemistry) and SHERLOC (Scanning for Habitable Environments with Raman & Luminescence for Organics & Chemicals).

Perseverance’s PIXL at Work on Mars (Illustration): In this illustration, NASA’s Perseverance Mars rover uses the Planetary Instrument for X-ray Lithochemistry (PIXL). Located on the turret at the end of the rover’s robotic arm, the X-ray spectrometer will help search for signs of ancient microbial life in rocks. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

“The more rocks you look at, the more you know,” Farley said.

And the more the team knows, the better samples they can ultimately collect with the drill on the rover’s arm. The best ones will be stored in special tubes and deposited in collections on the planet’s surface for eventual return to Earth.

More About the Mission

A key objective for Perseverance’s mission on Mars is astrobiology, including the search for signs of ancient microbial life. The rover will characterize the planet’s geology and past climate, pave the way for human exploration of the Red Planet, and be the first mission to collect and cache Martian rock and regolith (broken rock and dust).

Subsequent NASA missions, in cooperation with ESA (European Space Agency), would send spacecraft to Mars to collect these sealed samples from the surface and return them to Earth for in-depth analysis.

The Mars 2020 Perseverance mission is part of NASA’s Moon to Mars exploration approach, which includes Artemis missions to the Moon that will help prepare for human exploration of the Red Planet.

JPL, which is managed for NASA by Caltech in Pasadena, California, built and manages operations of the Perseverance rover.